Zohran Mamdani is the model of a political actor and thinker who is engaged in a new practice of philosophy. He is a critical theorist/political actor who is constantly confronting concrete political projects with philosophical principles, and vice versa. To elaborate on what I have in mind, I draw on the writings of the postwar French philosopher Louis Althusser, who, throughout his deeply problematic and troubled life, constantly struggled to provide the Left with a philosophical foundation and, in the process, developed one model of what he called “a new philosophical practice.”

Yearly Archives: 2025

What is the relationship between the form and political content of theological and philosophical traditions? This essay focuses on the early works of the French philosopher Louis Althusser, who, in the postwar period, tried to reconcile Christianity with Leftist politics and Hegelian philosophy. Althusser demonstrates how form and content can be linked, but in the end, more than anything, the essay underscores the need for the Left to develop a new comprehensive philosophy to inspire political action today. [Continue reading here]

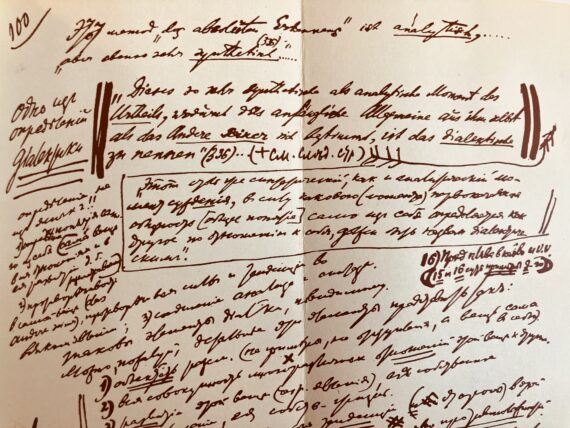

In this essay, I explore the far Right’s embrace of Lenin. I return to the Hegelian roots of Lenin’s politics to explain what he meant by “smashing the state machine.” I then argue that the Left should reclaim Lenin’s dialectics and his call, in the April Theses, for a second wave of social movements to overcome President Trump’s revolution. [Read more…]

Confronting Hegel and Project 2025 of the Heritage Foundation leads to a burning question: Does the Left need a new framework, and, if so, where would that new approach begin? Certainly not with the traditional family as in Hegel’s Principles of the Philosophy of Law, or in the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025. [Read more here]

Hegel 13/13 is a multi-year project that explores the historical confrontations with G.W.F. Hegel’s thought, from the nineteenth century to the present, with the aim of developing new critical perspectives and practices for today’s times. The ambition of this multi-year project is to serve as a catalyst to produce new forms of critique and praxis to address the present political conjuncture. [Continue reading here]

Foucault does not merely flirt with the vocabulary of Capital volume 1 but proposes instead to expand the Marxian theory of capitalist exploitation by analyzing the techniques of power that constitute proletarians as productive—and thus exploitable—subjects. [Continue reading here…]

What makes the final texts of Karl Marx so utterly fascinating and important is that they encapsulate Marx’s post-economic political thought: his political thinking after he had fully articulated his mature political-economic theories. [Continue reading here…]

A return to some of Marx’s lesser-known texts may help us articulate the links that exist between the commune as modern political form or strategy, typically associated with the heroic case of the Paris Commune, and the community or communality as forms of life with deep roots, especially in Latin America, in indigenous uses and customs that otherwise are alien or even opposed to the dream of Western modernity. [Continue reading here…]