A return to some of Marx’s lesser-known texts may help us articulate the links that exist between the commune as modern political form or strategy, typically associated with the heroic case of the Paris Commune, and the community or communality as forms of life with deep roots, especially in Latin America, in indigenous uses and customs that otherwise are alien or even opposed to the dream of Western modernity. [Continue reading here…]

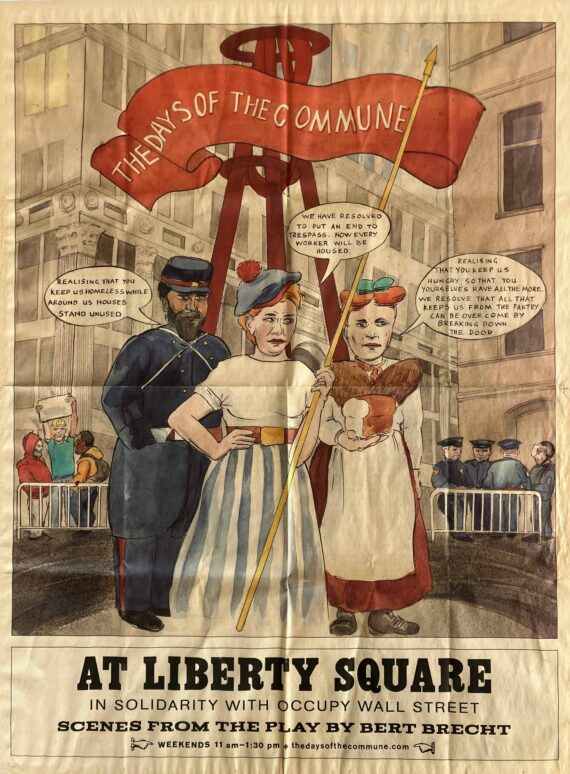

Few historical events or great defeats have inspired as much hope and inspiration, against all odds, as the Paris Commune of 1871. Voltairine de Cleyre’s “The Commune is Risen” (1912) and Plotino Rhodakanaty’s “The American Commune” (1877) are two brilliant illustrations of the lasting spirit of the Commune in the Americas. Marx’s address “The Civil War in France” is of course another standard-bearer. With Bruno Bosteels, we will be exploring these texts and their interrelations. [Continue reading here…]

Politically Red is a magnificent reading of Marx and his companions, Walter Benjamin, Rosa Luxemburg, W.E.B. Du Bois, Jameson, Cedric Robinson, and their interlocutors and readers. It is an archive embedded in a gallery of images, gorgeously reproduced, inspiring, mobilizing in their beauty, and evocative. Politically Red is a work of art, an ode to the red common-wealth. [Read more here…]

Read through the lens of scholars such as Kohei Saito, Marcello Musto, Teodor Shanin, Bruno Bosteels, Kolja Lindner, and others—scholars of the “Late Marx”—the final writings of Karl Marx constitute a very different Marx than the one that we are accustomed to, especially the Marx of the mature economic writings of Capital, Volume 1. [Continue reading here…]

Robinson’s Black Marxism has no ambition to be a strand of Marxism, nor to be genuinely Marxist. It too begins with a critique of Marx, namely its Eurocentrism, but it does not claim to reconstitute a form of Marxism. Instead, it unearths a history of European racialism that Marx ignored and develops instead a Black Radical tradition that is intended to be independent and autonomous of Marxism. [Continue reading here…]

The *Grundrisse*, a hefty volume running about a thousand pages long, has become the urtext for those readers of Marx who have sought to infuse the more scientific and economistic later Marx of the Capital with the earlier philosophical, political, and social theoretic Marx of the 1840s. For these readers, it serves as the final bridge to *Capital.* [Continue reading here…]

I would like to propose another reading of Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire– partial, perhaps even biased. This reading would in fact emphasize the complex conception of history that can be read between the lines. And since the seminar rule is to rely on a commentary, the reading I have chosen is that of Jacques Derrida, in Specters of Marx, published in 1993. [Continue reading here…]

We’re living in a period that is both pre-revolutionary and counter-revolutionary at the same time. Instead of leading to a radical questioning of the political and economic foundations of our social order, social unrest is leading to a conservative revolution in which the people give new credence to a leader. How can this be explained? In a way, this was already Marx’s question: why did the people support Louis-Bonaparte? [Continue reading here….]