By Chloe Howe Haralambous

On the morning of April 12, 2023, a 26-meter ship cut crisply through the waters of the Mediterranean with 800 people on board. Keeping an even keel, her skipper made for the Sicilian port of Catania where she docked, to the wonder and celebration of her passengers. Visible on her bow through a thin coat of paint, the ship’s name read “Kefah 1” or, “struggle.”[1]

The Kefah 1’s arrival marked the last in a spate of border crossings from Libya on that Easter weekend. But unlike the rubber dinghies and rotting trawlers that usually made the passage, she was a fair ship: a dazzling blue and white with a fine bridge and two radar antennae. To the Italian police authorities gathered on the quay, she looked uncannily familiar. It soon emerged, to public scandal, that years earlier, the ship had been part of the civil rescue fleet, employed by European activists and humanitarians to rescue migrants[2] attempting the passage to Europe. No one – least of all the rescue organizations in question – could explain how she had come under the command of the 800 border-crossers who had steered her from Benghazi to Sicily. But the Kefah’s Mediterranean life cycle – including its gaps and aporias – reflects the vicissitudes of the sea crossing at the height of Europe’s “refugee crisis.” Here, in preparation for our seminar, I want to follow the Kefah’s trail in order to orient us in that history as it developed between 2015 and 2021 – a rough periodization of the ‘rescue wars’ and the period at the heart of my own experience as an activist and researcher at sea. At the end of the post, I propose a few threads linking rescue at sea with the question of coöperism.

A Brief History of Search and Rescue

The Kefah 1 was still the Arctic exploration vessel, “Clupea,” when 368 people lost their lives in the October 2013 shipwreck offshore Lampedusa, bringing the mass drowning in the Mediterranean to the center of Europe’s political and affective life, engaging states, jurists and publics in the struggle to determine who had the obligation to save migrants from drowning and why. As an initial response, Italy launched a public rescue operation, Mare Nostrum, deploying ships to patrol the sea crossing and save people in distress. Under the aegis of Mare Nostrum, the death rate in the Mediterranean fell precipitously – so much so that members of the European Commission wondered whether the Italian rescue fleet was not acting as a “pull-factor,” enticing migrants to attempt the crossing and contributing to traffickers’ business model.

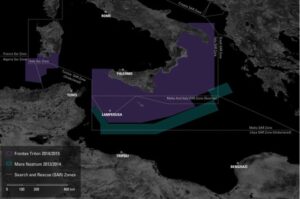

In late 2014, the European Union encouraged Italy to suspend Mare Nostrum in favor of the EU-wide Operation Triton, under the coordination of Frontex, the European Border Force. Soon after, in 2015, the European Naval Force (EUNavforMed) initiated its own Operation Sophia, supported by the NATO fleet already in the Mediterranean to enforce the arms embargo on Libya. In concert, these navy and police operations reshaped the agenda in the Mediterranean, focusing less on the mandate to save life at sea and emphasizing “control[ling] irregular migration flows towards the territory of the European Union and tackl[ing] cross-border crime.” The specter of the trafficker became a crucial enabler in justifying the increased militarization of the border. Recourse to the business avarice of the trafficker gave the continuing imperilment of migrants at sea a humanitarian gloss: it was not the EU border regime that was responsible for their death, but predatory human traffickers. In dismantling their cartels, European authorities claimed to be “protecting” migrants from exploitation. They did not, however, provide any safe alternative pathways to Europe. People continued to cross, but under increasingly dangerous conditions.

As a result of the withdrawal of rescue ships, 2015 became the Mediterranean’s deadliest year on record, prompting humanitarian giants such as Doctors without Borders and Save the Children to declare a “humanitarian emergency,” and to mount a civil rescue effort, chartering ships to the Mediterranean passage in order to fill “the rescue gap” left by Mare Nostrum. They were joined by a seed group of human rights groups and radical collectives from across Europe who sailed their own small, rickety ships to the Mediterranean.

Map showing the retreat of state search and rescue assets by comparing the operational zone of the Italian Navy Mare Nostrum operation and the EU border agency’s Triton Operation.[3]

Even as the rescue wars largely unfolded in the Central Mediterranean, many of the characters, practices and theoretical problems involved originated in the Eastern European border where, by 2015, the “long summer of migration” had begun. While the EU launched operations Triton and Sophia offshore Italy, thousands of people on the move set out from the Turkish coast, bound for the Greek islands. With the border regime temporarily overwhelmed and state infrastructures collapsed, civil society initiatives and good Samaritans of various political and/or humanitarian stripes descended on the Aegean. For many of the young Europeans among them, grassroots organizing around migration would prove a radicalizing experience. For some, that political education flourished at the conjuncture of the “refugee crisis” and the fiscal crisis of the Eurozone, with which it partially overlapped. I myself only arrived at border struggles in the Mediterranean to escape the failure of what had promised be a revolutionary struggle against austerity in Greece. In July 2015, when the governing coalition of the radical Left, Syriza, “capitulated” to a further spate of austerity, the Greek social movements that had brought it to power disbanded in protest; many of its militants found a new cause in migrant solidarity organizing, and carried over the principles of direct action, self-organizing, mutual aid and a ruthless critique of the European Union they had honed under austerity.

Until recently, a pipeline connected Europe’s maritime crossings: activists received their technical training and political education on the Aegean route before graduating to the large ships of the Central Mediterranean. In 2015 and 2016, that border internationalism – the circulation of people, funds and ideas from the squares to the borders of Southern Europe, and from the Aegean to the Central Mediterranean – fuelled the expansion of the civil fleet. Those on the left flank of the fleet pooled knowledge and skillsets from across activist groups to mount technically complex operations, involving ships, reconnaissance aircraft and a vast network of information exchange, data gathering and advocacy. It was in this period that the German activist collective, Sea-Watch, scaled up from its first ship, a twenty-meter shrimper built in 1917, and purchased the Clupea in Britain, re-outfitting her, and sailing her to the Mediterranean as the Dutch-flagged search and rescue ship, Sea-Watch 2.

The subsequent fortunes of the polyonymous Kefah 1 reflect the vicissitudes of the Search and Rescue zone as the European border regime recovered from its crisis and worked to seal the migrant corridor. In Italy, the government recalled all European state ships and outsourced the work of border control to Libya. A two-pronged judicial and political attack tried to chase NGOs out the Central Mediterranean. A taskforce of international and Italian policing agencies led by the Sicilian Antimafia launched a web of investigations into the civil fleet, with magistrates alleging that NGOs rescuing refugees were in fact colluding with people traffickers and others: priests, fishermen and border forces themselves. Despite the criminalization campaign against it, the civil fleet continued to expand, buoyed by a transnational grassroots movement that identified the Mediterranean as the heart of radical struggle in Europe. Sea-Watch graduated to an even larger ship, and handed the Sea-Watch 2 to the small German anarchist collective, Mission Lifeline, who renamed her, “Lifeline.”

I last saw the Lifeline from the deck of the Sea-Watch 3 in the high seas south of Malta. It was June 2018 and Italy’s newly instated minister for the interior, Matteo Salvini, had just made good on his election promise to seal all Italian ports to NGOs carrying migrants. Two days later, the crew of the Lifeline rescued 234 people. After six days adrift with no safe harbour open to them, they forced their way into the port of La Valletta, where the ship was seized by Maltese authorities and her captain arrested under allegations of people trafficking. Disowned by her flag state, and banned from conducting rescues, Mission Lifeline sold the ship on Ebay to a Maltese fisherman who flagged her to Libya and renamed her Nour 2. She disappeared into the ordinary bustle of the Mediterranean’s fishing fields only to resurface, briefly, in 2021. By that time, Italy’s administrative detention of civil rescue ships had forced NGOs to fall back on their reconnaissance aircraft, patrolling the sea passage on the lookout for boats in distress, pressuring (at times begging) nearby merchant vessels to intervene. Among the few sailors who habitually responded to the aircraft’s May Day relays for boats in distress was the captain of the Nour 2. Sea-Watch’s aircraft, Seabird, last spotted the blue and white cutter in January 2022, as she sailed full speed ahead to the coordinates of fifty people on board a drifting boat.

The Nour 2’s tracks fade after that. One (possibly apocryphal) account suggests that she was absorbed into the fleet of the Maltese mafia boss, Paul Attard, and used to smuggle drugs and oil across the Mediterranean. Regardless, the disappearance of the ship from the SAR zone reflected the petering out of the rescue wars – or at least the end of the political conjuncture in which the unique political constellations at the scene of shipwreck reverberated in the massive collective engagement with the question of rescue across Europe. The rescue wars were, in that sense, played out as much on land as at sea. Bridging ethnographic and literary study, my own work on rescue focuses on the dialectical relation between, on the one hand, the everyday struggles among migrants, coast guards, rescuers, NATO, fishermen and merchant ships at the sea border and, on the other, the imaginaries through which those encounters were publicly interpreted, politicized and, crucially, policed. Here, for the purposes of our seminar, I want to propose three potential avenues of discussion linking those struggles with the question of coöperism.

1) The first question regards political theory and praxis at sea. While they respond to many of the same pressures, border struggles in the high seas are different from those unfolding on the island, riverine or land passages to Europe; the reasons for this have as much to do with the saltwater medium as they do with a pre-existing cultural repertoire that has established the sea as a theater for social commentary, political aspiration and alternative forms of affiliation (consider the unique internationalism of sailors, the subversive potential of shipboard life instantiated by mutiny, piracy or slave revolt, the radical unities forged across difference by motley crews). While exposing the violence of Europe’s maritime border regime usually involves dispelling much of the romance of the world’s seas and oceans, as Miguel and I will elaborate, the maritime environment in general and the scene of rescue in particular do sometimes engender forms of cooperation typically foreclosed on land. For the (nominal, at least) sake of salvaging life, states, shipping tycoons, migrants and radicals form alliances across differences that chafe against established political orders and disrupt scalar hierarchies, conjuring new imaginaries and constellations: ships of the NATO fleet become pawns in the struggle between leftist collectives and European governments; Antimafia magistrates hypothesize collusion between humanitarians and traffickers; anarchist groups forge alliances with giants of global capital. So the first question I want to raise is: how does the practice of rescue at sea open up new imaginaries of solidarity and cooperation? How do we think with the sea – including with its perilous dimensions – to elaborate visions of coöperism that outlive the acute phase of necessity and go on to shape new political constellations on land?

2) The Civil Fleet is not internally uniform: at its peak, it included humanitarian giants such as Doctors without Borders (MSF) and Save the Children, alongside organizations such as Sea-Watch and Mediterranea who pride themselves on their expressly political (read non-humanitarian) mandate based on principles of solidarity, and whose institutional history has roots in the European New Left, in Italian Autonomism, in the anti-globalization and, later, anti-austerity movements. A second question I have is how solidarity at sea emerged out of the historical backdrop of class or anti-colonial struggle in which (many of) its activists were forged. How does coöperism built through the idioms and practices of humanitarianism (pertaining more to the salvage of life than to the politics of living) exemplify a broader trend in the humanitarianization of politics or, conversely, the politicization of humanitarianism on the Left?

3) My final question concerns coöperism in relation to the state. Beginning in 2016, and under the loose coordination of the Antimafia criminal justice project, Sicilian prosecutors opened dozens of investigations into civil rescuers accused of aiding and abetting illegal immigration. The police investigations into the rescue fleet adapted methods (wiretaps, bugs, undercover informants) and criminological paradigms such as “organized subversion” or “criminal association” that have long been used by the Italian Antimafia and anti-terror criminal justice projects: not only in their prosecution of the Mafia, but also in their hunt against brigands, left-wing terror groups such as the Red Brigades, and a plethora of organizations of the radical left seen as posing a threat to the democratic order.

Indeed, since late 2014, the civil fleet has shifted from an auxiliary to the state (filling the gap left by Mare Nostrum and acting under the coordination of European maritime authorities) to being, at times, a semi-autonomous cooperative practice and network aimed not only at saving life, but at keeping open migrants’ route to Europe. While it is important to stress that the fleet has always campaigned for the return of state-run rescue operations and has always sought to maintain a relationship with maritime authorities, it nevertheless, in some instances, openly positioned itself as an alter-state: “a no borders navy” coordinated by the civil maritime rescue operation center. As one prosecutor put it in his address to the Italian parliament in 2017:

Today, [the NGOs] are creating safe corridors that allow access to Italy, which is absolutely irregular, because we are dealing with traffic that would not exist if the NGOs had not created these corridors. So, I ask myself, but I assume that you are asking yourselves as well, because it’s your job: can private organizations be allowed to substitute political forces and the will of nations in creating these corridors and in deciding how to create these corridors. Can they be permitted to substitute the state?[4]

In other words, the NGOs whose involvement in the border was initially condoned– even requested – by the state, mobilized elements of state prerogative to carve out a field of operations that appears to be autonomous and opposed to the state, undermining its monopoly not only over the right to control its territory by defining and vouchsafing its borders, but also over the legitimating discourses upholding the border, which civil rescuers claim for themselves by appealing not to the order of the Italian state but to that of human rights, solidarity and humanity – principles the state shares (not least in its own legal rendering of the duty to rescue at sea), but which it cannot monopolize.

One final avenue for discussion I’d like to pursue is to think with the political imaginary underlying the prosecution of sea rescue as a form of organized subversion. How can we use it to elaborate the place of coöperism in the relationship between the state and civil society as it is, or as we want it to be, negotiated?

For more readings and to watch the seminar, go to Coöperism 11/13

Notes

[1] Nicolò Zancan, “Sul barcone degli ultimi, quasi 800 persone ammassate sulla Kefah1 per un viaggio da 250 euro a persona,” La Stampa, 13 April 2023, https://www.lastampa.it/cronaca/2023/04/13/news/sul_barcone_degli_ultimi_quasi_800_persone_ammassate_sulla_kefah1_per_un_viaggio_da_250_euro_a_persona-12750655/.

[2] I use the term “migrant” as an umbrella term for people who cross, or attempt to cross, the Mediterranean border to reach Europe. They do so for a variety of reasons: from the search for refuge and economic security to the advancement of political struggles.

[3]GIS analysis: Vanessa Guglielmi. Design: Samaneh Moafi. In Lorenzo Pezzani, “Liquid violence: investigations of boundaries at sea by Forensic Oceanography,” The Architecture Review, April 10, 2019. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/liquid-violence-investigations-of-boundaries-at-sea-by-forensic-oceanography.

[4] Carmelo Zuccaro, interviewed by Paula Ravetto. Indagine conoscitiva sui flussi migratori in europa attraverso l’italia, nella prospettiva della riforma del sistema europeo comune d’asilo e della revisione dei modelli di accoglienza. Rome, September 10, 2015, https://documenti.camera.it/leg17/resoconti/commissioni/stenografici/html/30/indag/c30_flussi/2015/09/10/indice_stenografico.0041.html