By Suzanne Cope, author of Power Hungry: Women of the Black Panther Party and Freedom Summer and Their Fight to Feed a Movement (Chicago Review Press, 2021).

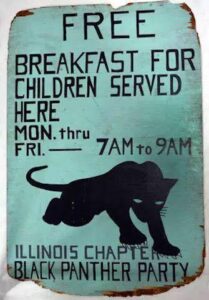

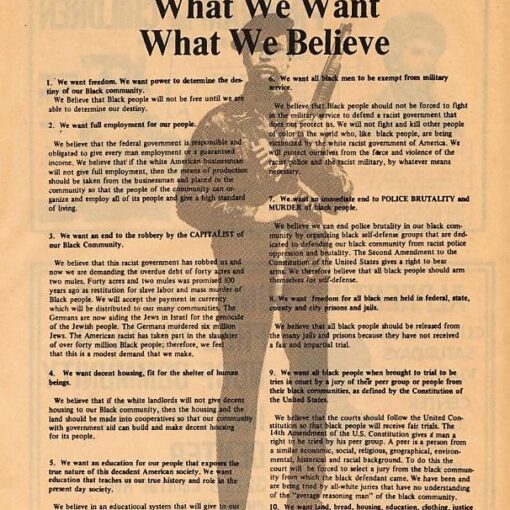

My book Power Hungry: Women of the Black Panther Party and Freedom Summer and Their Fight to Feed a Movement was inspired by my research into food as a tool for social and political change. Making and consuming food is, inherently, a cooperative activity. And these acts, as food studies scholars have noted, derive much of their power from being a communal activity. This had such resonance in the Black Panther Party’s work, especially, as I discussed with the main subject of my book, as reflected by Cleo Silvers. Of course, the Free Breakfast for Children program fulfilled specific needs: of feeding children and getting them to school. But it was also the choice of food, how the Panthers sourced the food, who made the food, and everything that happened during and around eating: homework help, Black history, and the mentoring from young, smart people in the young childrens’ community. Beyond the breakfast program there were also other ways that food was used in a cooperative way, for community building and mentoring young people, and the Black Panthers also harnessed this kind of cooperative leadership in other survival programs.

Further, the amount of coordination — and cooperation! — that had to occur to actually run the breakfast program was astounding. Food had to be regularly sourced, transported, safely stored, with teams of people dedicated to picking up the children, cooking the food (starting quite early!), cleaning up, walking the kids to school, etc. Much of this labor was expected of the women — who made up at least 2/3 of the Party during its peak. And these female leaders from around the country helped feed more children breakfast than the state of California on any given weekday morning.

And the Free Breakfast for Children Program was just one of many survival programs that were organized in a similar way. There are many examples, but one I will highlight is the Black Panther’s work around community health care. This also has at its core a necessity of cooperation among many stakeholders: community facilitators (who were often Party members), doctors, nurses, and community members. This approach to healthcare — even today — is seen as progressive and revolutionary and is tied to many positive outcomes. It is also the antithesis of most top-down, doctor- and insurance-driven health care that often fails, in particular, people of color and those of low socio-economic status.

Which brings me to the concept of activist mothering. Often this kind of gendered work is as overlooked as it is essential. It takes great skill to facilitate this kind of cooperation, even as it is often downplayed as a feminized activity, and considered easy or a given that women can or would do this work. But it is hard work and skilled work. And, of course, with the Panthers many men did the more feminized work of cooking, serving food, cleaning up, and general child care, community outreach and nursing, as the non-gendered mission of the Party dictated. Of course, as Cleo and other Panthers noted, the Panthers were part of the same patriarchal society as everyone else, so this shift in thinking was never executed perfectly.

But I do believe that the food programs in particular – but also the many survival programs overall – elevated the skills of women, showing us today how important this kind of cooperative leadership was and still is. It is a hope that we can value these activist mothers in a new way by looking at their skills and contributions through this lens.