For Toni Negri, Marx’s Grundrisse allowed him to address a double crisis of Marxism: a crisis of “official” Marxism, represented in Italy primarily by the theoreticians of the Italian Communist Party and the interpretations of Capital; and a crisis of the revolutionary workers movement and the entire set of liberation movements active at the time. [Continue reading here…]

J’aimerais proposer une autre lecture du Dix-huit Brumaire de Louis Bonaparte de Marx– partielle, partiale, peut-être même biaisée. Cette lecture voudrait en effet insister sur la conception de l’histoire complexe que l’on peut lire entre les lignes. Et puisque la règle du séminaire est de s’appuyer sur un commentaire, la lecture que j’ai choisie est celle de Jacques Derrida, dans Spectres de Marx, en 1993. [Continuer à lire ici…]

As Seyla Benhabib notes in her book The Reluctant Modernism of Hannah Arendt (2003), “the aspect of Arendt’s theory of human activity that has been most criticized and discussed … is the distinction between labor and work.” (130) In this keynote lecture by Professor Benhabib, the Eugene Meyer Professor of Political Science and Philosophy emeritus at Yale University, senior research scholar at the Columbia Center for Contemporary Critical Thought (CCCCT), professor at Columbia Law School, and a foremost authority on Arendt, we will explore the controversy over Arendt’s reading of Marx. [Continue reading here…]

We are witnessing today a new and radical offensive in the American Counterrevolution. The Counterrevolution itself is not new—as Marcuse shows well—but we face a new front. We are in the demolition phase of a new offensive of the Counterrevolution. President Trump is taking a bulldozer to the existing federal government, tearing down its foundations, in an effort to eradicate the liberal regulatory state and replace it with an oligarchic-theological, fealty-based, cult of the leader regime, with an authoritarian grip. It is a counter-offensive of revolutionary scale. And it has been made possible by an unexpected coalition of forces—of seemingly odd bedfellows—including tech billionaires, populist nationalists, evangelicals, rural voters, young “tech bros,” as well as, frittering away at traditionally Democratic constituencies, many union members, and now increasingly Black and Latino men. [Continue reading here…]

We are experiencing right now, in the first few weeks of the second Trump presidency, the triumph of a new offensive of the American Counterrevolution. It is critical that we understand this moment. Few texts are more important to do that than Engel’s Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany 1848 and Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon. [Continue reading here…]

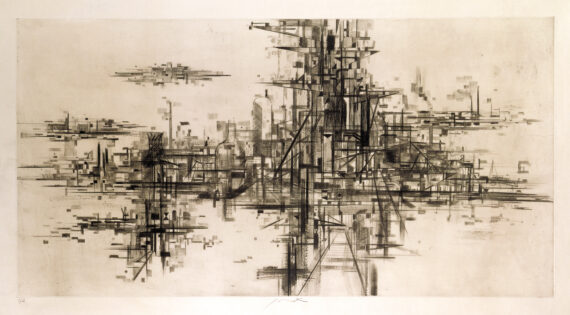

In a series of articles published in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung in 1850, Marx offers a sweeping historical account of the French revolution of 1848. Marx theorizes at the same time as he recounts history, and vice versa: he confronts theoretical insights and hypotheses with historical developments, statistics, economic research, and first-hand accounts. The articles are political, engaged, opinionated, often satirical and witty, biting at times, punchy, and rallying. Reading them, one senses that they are a call to revolution. [Continue reading here…]

Lenin’s April Theses can be seen as a rewriting and completion of the Communist Manifesto. This continuity becomes apparent in two prefaces Marx and Engels wrote for later editions of the Communist Manifesto. Let me begin with the preface to the edition of 1872. [Continue reading here…]

The Communist Manifesto enclose within it traces of the uprisings that birthed it. It is a document whose theories arise from and are amended by social movements. Importantly, it is written for the ordinary worker, who as Engels commented in its 1888 English preface, acknowledged it as their “common platform…from Siberia to California.” It is in this specific sense of a document arising from a movement that we chose to call our work a “manifesto”, for, although in a less grand scale, our manifesto too arose from the wave of feminist strikes, and both contributed to and were recalibrated by them. In this brief reflection I hope to draw out some of the ways in which our Manifesto stands in the tradition of Marxist theorizing of capitalism, and in one key way makes a contribution to it. [Keep reading here…]