By Benjamin P. Davis

Simone Weil’s personal notebooks contained several references to the soldier and historian Thucydides, whom she returned to in 1939. It is from his History of the Peloponnesian War that we can start to gain a sense of how Weil understands war.

In the sixteenth year of that war, the powerful Athenians—and a number of their allies—sailed to the isle of Melos, one of the few Aegean islands that remained outside of Athens’ sphere of influence. Thucydides notes that it was only after the Athenians plundered Melian resources and exercised violence against their people that the Melians adopted a position of hostility toward the Athenians.

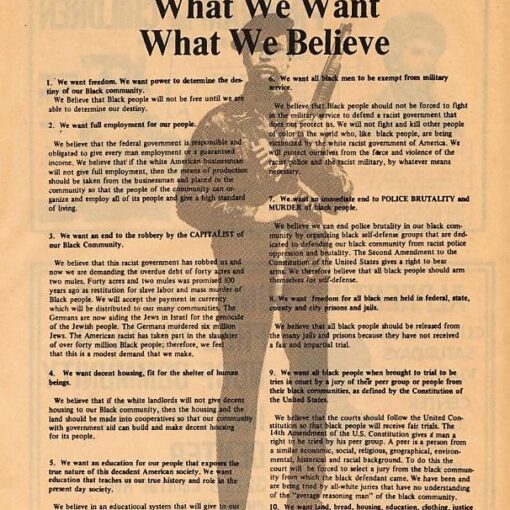

While the Athenians maintain the pretext of negotiation, the Melian representatives see the arrival of Athenian ships, infantry, and archers for what it really is: a choice between war and slavery, fighting or submission. What is right or just, the Athenians state in response to the Melians’ concern for “the safety of our country,” is only a question “between equals in power.” In contexts of great asymmetry, the Athenians go on to assert famously, “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

But the Melians did not want to talk about power instead of about justice—they did not want “to let right alone.” They worried that the Athenian approach would destroy not only their livelihood but also “our common protection,” namely, “the privilege of being allowed in danger to invoke what is fair and right.”

Still, the Athenians pressed on, saying, “We will now proceed to show you that we have come here in the interest of our empire,” stressing that they will “exercise that empire over you without trouble” and adding that “we should gain in security by your subjection.”

At the close of the “conference,” the Athenians hold firm, counseling that “it is certain that those who do not yield to their equals, who keep terms with their superiors, and are moderate towards their inferiors, on the whole succeed best,” and then they withdraw from the conference.

But so too do the Melians hold firm, noting that, having lived on their land for hundreds of years, their resolution “is the same as it was at first.”

In response, Athens puts Melos under siege and leaves “the allies to keep guard by land and sea.”

As the seasons pass, the Melians continue to engage in what we would now call guerilla warfare—attacking by night, for example, to take needed food and fuel back with them. But the Athenians sent in reinforcements and strengthened the grip of their control—“the siege was now pressed vigorously,” Thucydides writes.

Then the Melians surrendered—only to suffer the death of their grown men, their women and children being sold into slavery, and five hundred Athenian colonists sent out to inhabit Melos.

***

When Simone Weil thought of war, she not only considered the conflicts of her time, which she studied intensely and even participated in directly, but she also thought back to the ancient Greeks, with the Melian dialogue ever echoing in her mind.

After Hitler violated the Munich Agreement and invaded Prague in March 1939, Simone Weil held to, but started to re-configure, her pacificism. By the formation of the military alliance between Germany and Italy in May 1939, she had renounced her pacifist commitments. It was not that she was wrong in holding such a position before, she now argued, but only that pacifism no longer applied in her increasingly forceful context. Moreover, she now wanted to fight on the front lines.

On a more abstract level, in response to learning that the Germans repressed a student revolt in Prague, Weil developed a plan for a French parachute corps that would both rescue prisoners and foster revolution in, via importing guns to, Czechoslovakia. Because her reputation of being a Communist hindered the adoption of this plan—she bought newspapers for weeks to check (with no avail) whether her radical plan had been adopted—Weil wrote a public declaration that she had never been a member of the Communist party.

Following the outbreak of war in France in early September 1939, in Weil’s circles the idea circulated that the objective must be to destroy Germany as a nation. Weil, by contrast, argued that Nazi Germany was only part of the problem of modern civilization, which, with its tendency toward universal conquest, itself made Nazi Germany possible.

Weil articulated her arguments in the essay “Some Reflections on the Origins of Hitlerism,” published in part on 1 January 1940 in Nouveaux Cahiers. There Weil claimed, in a decidedly contrarian position at the time, that modernity’s move toward domination was an educational problem. In her view, Western education trained students to admire Rome for its conquests and empire, and in this way, one legacy of Rome was how it taught modern-nation states, in their curricula and media, to link together power, prestige, and expansion.

In a later part of that essay, Weil argued that Rome also invested its power with the appearance of legality. In a conclusion that relates to her critique of the Old Testament, Weil writes, “If I admire, or even excuse, a brutal act committed two thousand years ago, it means that my thought, today, is lacking in the virtue of humanity… it is impossible to admire certain methods employed in the past without awakening in oneself a disposition to copy them.”

Around the same time in 1939 and 1940, Weil started drafting a never-fished article entitled “Reflections on Barbarism.” In this article, she argued that barbarism is not of certain groups but is rather “a permanent and universal human characteristic.” Put differently, she writes, “[W]e are always barbarous toward the weak unless we make an effort of generosity that is as rare as genius.” In an important statement of the method she was developing, in “Reflections on Barbarism” she also wrote: “I believe that the concept of force must be made central in any attempt to think clearly about human relations.”

Departing from how Hegel centered Geist or Marx focused on class, Weil, by late 1939, had started to see force as the key to history. The concept of force would motivate her subsequent and much more famous essay “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force.” Weil herself translated the Greek she would use in that essay. In an original reading of Homer, she argued that the main character of the Iliad is force itself. She also stressed that it was not just those who suffer force who are controlled by it, but in fact those who wield it are also under its seductive control.

Further, even when force is not exercised immediately but hinted at or used to threaten, Weil observed, it is present and acting on us. In “The Iliad” she described this twofold sense of force in terms of “the force that kills” and the force “that does not kill just yet,” adding that “[i]t will surely kill, it will possibly kill, or perhaps it merely hangs, poised and ready, over the head of the creature it can kill, at any moment, which is to say at every moment.”

In sum, from Thucydides Weil gained a continued alertness to asymmetries in power, such that she would come to think of ethics in a context of war as exemplified in a refusal to exercise power, what Yoon Sook Cha describes as “a negative use of power.” While this refusal to exercise power does not by itself change the conditions that led to the asymmetry in the first place, it does underscore that there always remains an available alternative action to the Athenians’ so-called realistic line in the Melian dialogue that always and as if by nature “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

And from Homer Weil gained insight into how humans do not and cannot control force, because force instead controls us. This insight, especially as it follows her renunciation of pacifism, only makes more important her negative ethic of power, because it reminds us that if and when we chose to exercise our power, we are entering into a process that we cannot control.

***

To bring into further relief how Weil understood war, we can compare her position to one of her contemporaries, Hannah Arendt, as well as to one of ours, Noura Erakat. Like Weil—and relevant to the situation of this discussion at a school that trains lawyers—both Arendt and Erakat offer reflections on the relationship between force and law, particularly with respect to the question of war, genocide, and the violence of the nation-state.

In the Epilogue to her book on the trial of the Nazi bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, the philosopher Hannah Arendt returned to the importance of international law, her critique of appeals to human rights (as opposed to the rights of citizens) somewhat notwithstanding. She writes, “If genocide is an actual possibility of the future, then no people on earth… can feel reasonably sure of its continued existence without the help and the protection of international law.” Even if Arendt’s ethics in that book combines “thinking from the standpoint of somebody else” and the insistence “that human beings be capable of telling right from wrong even when all they have to guide them is their own judgment,” her politics returns to the importance of law among nations.

In our own time, in her book Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine, the human rights lawyer Noura Erakat has noted that international law is itself a form of asymmetrical power. “[L]ike all other structural asymmetries,” she goes on, international law is “brutally unfair and inescapable.” However, Erakat frames law as “like the sail of a boat,” meaning that political movements can shape how and where the law moves; mass mobilization remains “the wind that determines direction.” “It is this indeterminacy in law,” Erakat maintains, in addition to “its utility as a means to dominate as well as to fight that makes it at once a site of oppression and of resistance; at once a source of legitimacy and a legitimating veneer for bare violence; and at once the target of protest and a tool for protest” (emphasis mine).

In sharp contrast to both Arendt and Erakat, Weil does not place her faith in rights, law, or social movements. In part because of how she read the Athenians as holding fast to their empire while throwing out the question of what is ethical, Weil always struggled to see human collectivity, including international collectives and their laws, as a site of justice. Because of how she read force in Homer—not as a tool we can use but as something that controls us—she didn’t see in structural asymmetries much room to maneuver. Further, she always kept close Plato’s description, in his Republic, of human social life as a “Great Beast,” and by the end of her short life she diagnosed in rights claims a “commercial flavor” advanced through “a tone of contention” as opposed to a spirit of attention.

Ultimately, then, if we are return to Weil to consider war, genocide, and siege, we might find a philosopher who asks us first to consider our own limitations and finitude as humans, who asks us to recognize how easily we can be swayed by nationalist thinking as well as by any use of power we think we can control. For Simone Weil, the only just response to power is the refusal to use it. It is a negative use, a task that asks us not “to let right alone” but “to let force alone.”

Simone Weil offers us a critical, political, educational, and legal task so striking in its strangeness, so foreign to history, that it would perhaps take divine inspiration to be carried out. Or at least, as she would write in her essay “Forms of the Implicit Love of God,” again returning to Thucydides in April 1942, to use asymmetrical force is to foreclose a relationship not just with others but also with the ethically and theologically charged world around us: “Those of the Athenians who massacred the inhabitants of Melos no longer had any idea of God.”

Surely she would say the same about the allies who stayed by to “keep guard by land and sea.”

***