By Bernard E. Harcourt

Abstract

The far Right in America has become radical. In the process, it has outmaneuvered the progressives. In the first months of his second mandate, President Trump has mounted a revolution (or counterrevolution) against the liberal democratic state. Steve Bannon said he was Leninist and wanted to “smash the state.” President Trump has done just that.

In this essay, I explore the far Right’s embrace of Lenin. I return to the Hegelian roots of Lenin’s politics to explain what he meant by “smashing the state machine.” I then argue that the Left should reclaim Lenin’s dialectics and his call, in the April Theses, for a second wave of social movements to overcome President Trump’s revolution. The time is right. The American people are hungry for a more radical politics—one that is centered on solidarity and cooperation rather than on hate, exclusion, and violence.

What Is To Be Done about the Radical Far-Right?

At a previous seminar in February 2025, one month into President Donald Trump’s second mandate, the critic W.J.T. Mitchell intervened in the discussion to make what he considered a conservative point: Mitchell called for the “restoration” of the liberal order. President Trump had only been in power for a few weeks, but had already dismantled U.S. AID and the Department of Education, fired legions of federal workers, seized control of independent agencies, and withdrawn from international institutions and accords. Mitchell, who identifies as progressive, did not call for revolution or radical change, but simply for a return to the status quo.

Trump was smashing the state. Mitchell was calling for a restoration.

Many of us in the seminar could not help but agree with Mitchell. The radical changes that President Trump was foisting on the country and the global order, in just a few weeks, were unprecedented and deeply threatening.

And yet Mitchell’s intervention—and my positive reaction at the time—still leaves me puzzled today: How is it that so many of us on the Left have become so conservative? What ever happened to the radical ideas of smashing the state, destroying the old, and ringing in the new? Where had our abolitionist instincts gone, especially the call to defund the police and shutter the institutions of the punitive society? Did the Left really simply want to restore the American state, with all its neoliberal hypocrisy, militarization, and mass incarceration?

To formulate the question in another way: Since when had the Left given up on the idea of radically transforming society and the state, and creating a new world order? What explains the resistance on the Left to a more radical strategy of taking advantage of President Trump’s dismantling of the neoliberal state and then, in the chaos, seizing power and reorienting politics in a truly progressive direction?

The Radical Right

The radicalization of the Right has a long history in the United States. It stretches back to Presidents Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon, to Senators Barry Goldwater, Strom Thurmond, and Joseph McCarthy, among others, or further back to the attack on Reconstruction in the 1870s, or even to the Southern secession. In recent times, though, the Tea Party movement is what turned the far Right radical.

Steve Bannon, a key figure in the Tea Party, actually self-identified as Leninist back in 2016. Bannon was the East Coast coordinator of the Tea Party groups at the time, and he would shortly become chief strategist during the first eight months of the first Trump presidency. In a conversation with Ronald Radosh, Bannon reportedly said: “I am a Leninist.”[1] When asked what he meant by that, Bannon reportedly responded: “Lenin wanted to destroy the state and that’s my goal too. I want to bring everything crashing down and destroy all of today’s establishment.”

For Bannon, the traditional American conservatives were too moderate. The Republican Party was not radical enough. Even the National Review and The Weekly Standard, well-known neo-conservative outlets were, in Bannon’s words, “left-wing magazines, and I want to destroy them also.” Bannon set his sights on smashing the entire political establishment, including the Republican Party and its leadership in Congress, and building a new political system based on Tea Party (and now MAGA) principles.

Many others on the far Right, like the activist Christopher Rufo, claim to be radical as well. In an interview on The New York Times’ podcast, The Daily, on April 11, 2025, Rufo states: “I think that actually we are a counter radical force in American life that, paradoxically, has to use what many see as radical techniques.”[2]

Now, it is Lenin who most famously called for smashing the state. And this raises a real puzzle: How is it that the far Right today has become Leninist and the Left Burkean?

Smashing the State

Lenin famously advocated smashing the state in the months leading up to the October 1917 Bolshevik revolution in his book The State and Revolution, which was published a few months later in 1918. Lenin was confronting the social-democratic strategy of using the electoral process to move the state into socialism, and he advocated instead for a more radical approach, namely to break and smash the state machinery. He attributed this more radical approach to Marx, more specifically to the Marx of 1852. Lenin wrote:

In this remarkable argument [The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon], Marxism takes a tremendous step forward compared with the Communist Manifesto. In the latter, the question of the state is still treated in an extremely abstract manner, in the most general terms and expressions. In the above-quoted passage [The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon], the question is treated in a concrete manner, and the conclusion is extremely precise, definite, practical and palpable: all previous revolutions perfected the state machine, whereas it must be broken, smashed.

This conclusion is the chief and fundamental point in the Marxist theory of the state. And it is precisely this fundamental point which has been completely ignored by the dominant official Social-Democratic parties and, indeed, distorted (as we shall see later) by the foremost theoretician of the Second International, Karl Kautsky.[3]

The Communist Manifesto, Lenin argued, did not address the key question of how a proletarian state could displace a bourgeois state, as a historical and practical matter. It was silent on the actual method of transformation. By contrast, Marx specifically answered that question in The Eighteenth Brumaire. Lenin goes on to say:

This is the question Marx raises and answers in 1852. True to his philosophy of dialectical materialism, Marx takes as his basis the historical experience of the great years of revolution, 1848 to 1851. Here, as everywhere else, his theory is a summing up of experience, illuminated by a profound philosophical conception of the world and a rich knowledge of history.[4]

Lenin’s mention of Marx’s “profound philosophical conception of the world” was a reference to Marx’s deep and constant engagement with Hegel’s writings. And in this regard, as Kevin B. Anderson remarks, Lenin was also referencing his own study of Hegel in 1914-1915.[5]

Some might argue that Lenin’s call to “smash the state” was decidedly “unhegelian,” not only because the state is the pinnacle of the realization of freedom in Hegel’s political thought, but also because the idea sounds undialectical. It seems to assume the possibility of the end of the state, or the end of history, and that seems to undermine the dialectical movement in Hegel’s thought (even if many scholars of Hegel, notoriously Alexandre Kojève, read him to argue for an end of history).

I would argue, instead, that Lenin’s call to “smash the state machine” was entirely hegelian and must be understood as the product of Lenin’s study of Hegel in 1914-1915. It may be helpful, then, to return to Lenin’s confrontation with Hegel’s Science of Logic, to make sense of his later politics in 1917. It will give us a better grasp of the idea of “smashing the state machine”—what that might mean, and how we might redeploy the idea on the Left today.

Lenin’s Return to Hegel

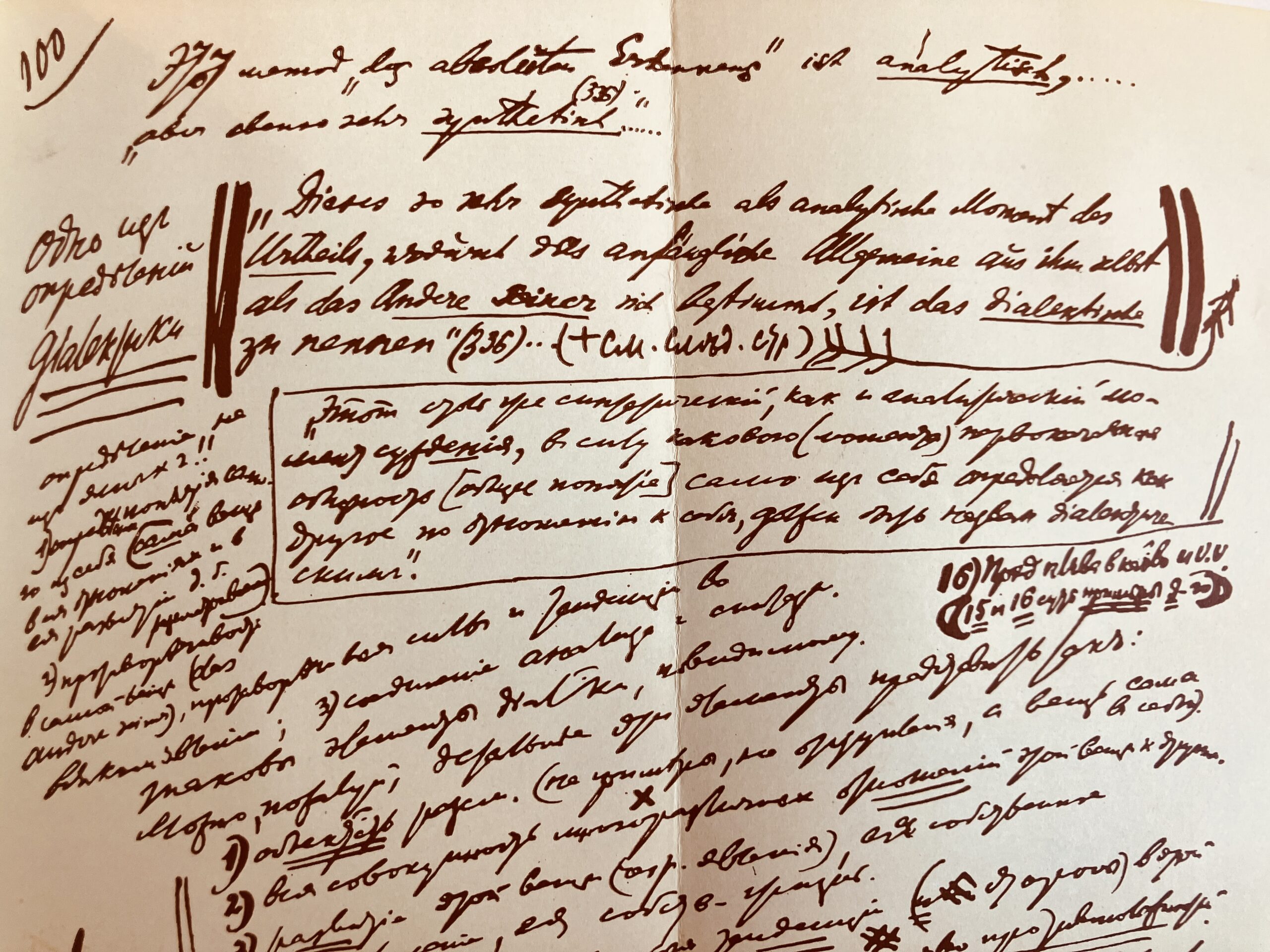

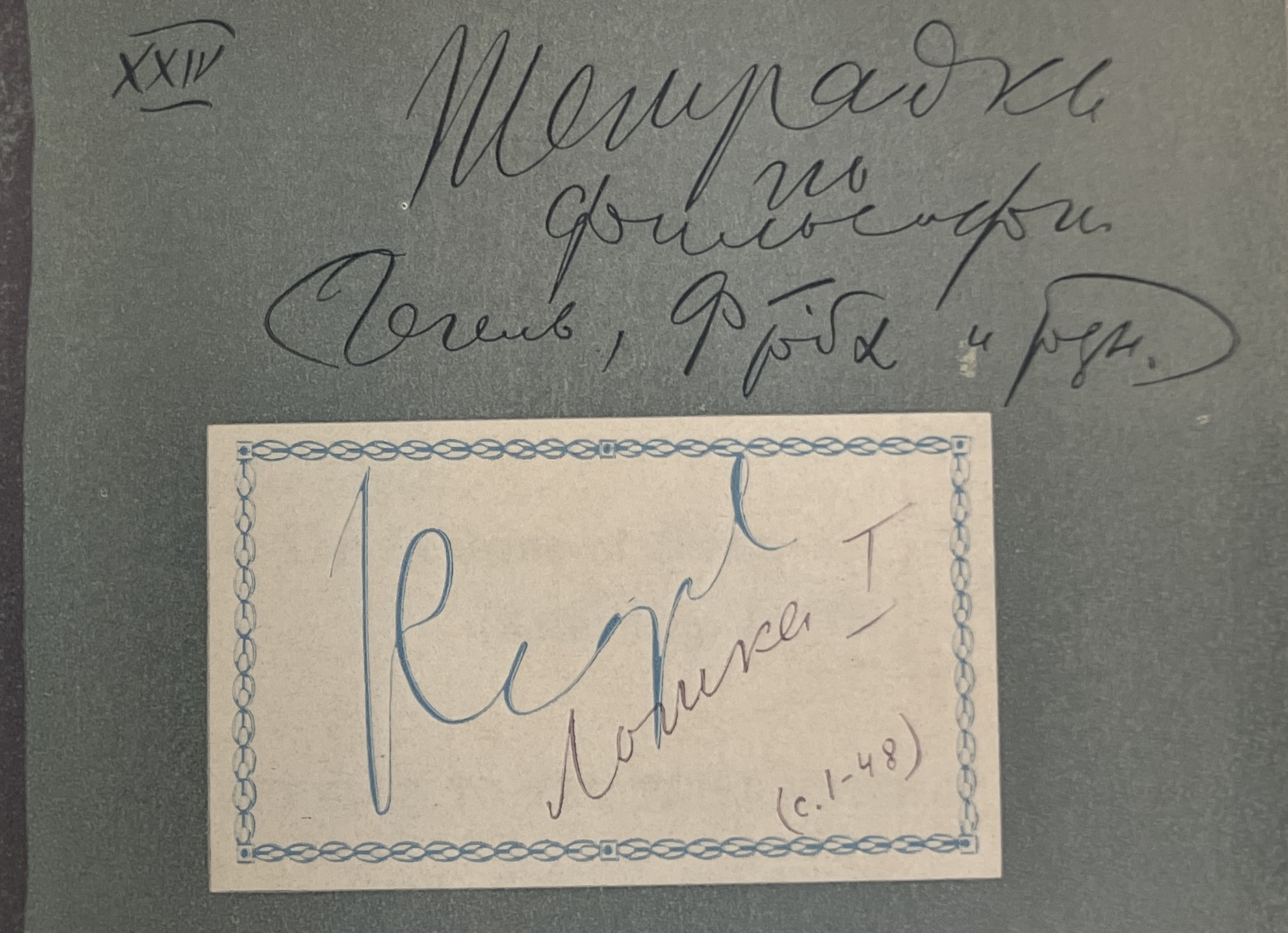

In his darkest hour, at the outbreak of World War I, at a time when internationalist workers’ parties turned nationalistic and patriotic, and the Second International collapsed, Lenin plunged into a months-long study of Hegel’s Science of Logic. In the reading room of the Bern library in Switzerland, in exile, Lenin buried himself in Hegel’s writings, copying passages, annotating them, writing commentary.

The experience was formative. As Lenin famously exclaimed in his Philosophical Notebooks—in perhaps the most famous passage—reading Hegel was essential to understanding Marx: “Aphorism: It is impossible completely to understand Marx’s Capital, and especially its first chapter, without having thoroughly studied and understood the whole of Hegel’s Logic. Consequently, half a century later none of the Marxists understood Marx!!”[6]

Scholars from Georg Lukács, Henri Lefebvre, C.L.R. James, Raya Dunayevskaya, Louis Althusser, Elias Murqus, Kevin B. Anderson, and Slavoj Žižek, and figures like Mao himself (especially in On Contradiction in 1937), have for decades now drawn our attention to Lenin’s reading of Hegel. In this regard, I highly recommend Anderson’s 1995 study, Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism: A Critical Study, as well as a brilliant seminar with Columbia faculty, colleagues, and students on Lenin’s reading of Hegel at Hegel 13/13 on October 8, 2025.

On my reading, Lenin found two interrelated ideas of greatest interest in Hegel’s writings: first, the element of “self-movement” at the heart of all life and societal change; and second, how that element of self-movement feeds a dialectical process.

First, throughout his commentary, Lenin focuses on movement, more specifically on what he calls “self-movement.” As Stathis Gourgouris emphasized at our recent seminar, Lenin placed the emphasis on the “self” in “self-movement”: it is a process that comes from within, that is immanent. In a telling passage, Lenin writes:

Movement and “self-m o v e m e n t” (this NB! arbitrary (independent), spontaneous, internally-necessary movement), “change,’’ “movement and vitality,” “the principle of all self-movement,” “impulse” (Trieb) to “movement” and to “activity”—the opposite to “d e a d B e i n g”—who would believe that this is the core of “Hegelianism,” of abstract and abstrusen (ponderous, absurd?) Hegelianism?? This core had to be discovered, understood, hinüberretten [rescued], laid bare, refined, which is precisely what Marx and Engels did.

The idea of universal movement and change (1813 Logic) was conjectured before its application to life and society. In regard to society it was proclaimed earlier (1847) than it was demonstrated in application to man (1859).[7]

Lenin elaborates on these Hegelian notions in his essay On the Question of Dialectics in 1915. There, he underscores that there are two ways to interpret the conception of “movement” at the heart of historical change: the first is the idea that historical development is a back and forth, a repetition, or what he calls “increases and decreases”; the second is the idea of historical development as the “unity of opposites” or “the division of a unity into mutually exclusive opposites and their reciprocal relation.”[8] The second, of course, is the Hegelian or dialectical approach.

According to Lenin, the first interpretation fails to understand the source of the historical development because it fails to see that the movement is internal. Instead, it projects an external driving force, like God or a subject. It is, he writes, “lifeless, pale and dry.”[9]

By contrast, the second, more Hegelian approach focuses on self-movement and as a result, offers a key to unlock the movement of history: “it alone furnishes the key to ‘leaps,’ to the ‘break in continuity,’ to the ‘transformation into the opposite,’ to the destruction of the old and the emergence of the new.”[10]

This unity of opposites, Lenin claims, helps understand all historical phenomena. In his words, it provides “the recognition (discovery) of the contradictory, mutually exclusive, opposite tendencies in all phenomena and processes of nature (including mind and society). The condition for the knowledge of all processes of the world in their ‘self-movement,’ in their spontaneous development, in their real life, is the knowledge of them as a unity of opposites.”[11]

Self-Movement in Action

Lenin’s meditations on self-movement in 1914-15 shaped his political views and praxis in the years that followed—some of the most consequential years for Lenin and Russia.

Following the first revolution of February 1917, which brought about the abdication of Nicholas II, Lenin called for a second workers’ revolution. In the April Theses, pronounced that month in 1917—again, shortly after his study of Hegel’s Science of Logic—Lenin argued that the Bolsheviks needed to mount a second proletarian revolution on the heels of the first bourgeois revolution. That alone would guarantee political change. Lenin wrote:

The specific feature of the present situation in Russia is that the country is passing from the first stage of the revolution—which, owing to the insufficient class-consciousness and organisation of the proletariat, placed power in the hands of the bourgeoisie—to its second stage, which must place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest sections of the peasants.

Lenin’s call for a second revolution can be understood, I suggest, through the lens of that second living conception of self-movement, the one that Lenin had just discovered a few months earlier in Hegel’s Science of Logic. It represents the historical leap, break, transformation associated with “the destruction of the old and the emergence of the new.”

And it resonates today as well.

The First Trump Revolution (or Counterrevolution)

What we are experiencing today, in the first year of the second Trump mandate, is actually the equivalent of a first bourgeois revolution. The Trump (counter)revolution is toppling the established political order.

President Trump’s (counter)revolution is “bourgeois” in the sense that it is an alliance formed primarily of well-off retired middle-class people and a handful of billionaires. The MAGA movement today is predominantly (at least 60%) white, Christian, and male, and a majority are retired and over 65 years of age.[12] These are the bourgeois in America today. They are the middle class. And they have flocked in droves to the MAGA camp. So, although President Trump may be benefiting mostly billionaires (through tax reform and government contracts), his revolution closely parallels the conventional bourgeois revolutions of the eighteenth and twentieth centuries.

Now, in those conventional first revolutions—which we often refer to as modern revolutions following Reinhart Koselleck—the bourgeoisie toppled an autocrat, Louis XVI in the case of the French Revolution, Tsar Nicholas II in the case of the February Revolution in Russia, George III in the case of the American colonies.

By contrast, here in the United States there was no autocrat. In fact, it is President Trump who is acting like an autocrat and seizing imperial powers. But I take it, from the point of view of the MAGA base, the autocratic power that is being dismantled is a perceived “deep state” made up of Washington insiders and East Coast liberals who have entrenched their power and resources.

There is a widely shared perception among MAGA proponents, and in fact more broadly, that the American political system is broken and only benefiting the liberal elites. Laced through these criticisms, there is the idea that power is concentrated in the hands of a cabal of technocratic and well-connected elites.

So, there is an analogous element, in the MAGA revolution, of unseating autocratic or concentrated power. What is missing, of course, are the large-scale societal upheavals that triggered the modern revolutions. The disastrous world war in the case of Russia. Bread shortages in the case of France. Although perhaps we can imagine the social media revolution and the advent of AI, as well as globalization and climate change, as upheavals that have fueled the revolutionary sentiment.

A Second Revolution

The key question this raises is why the Left today is not calling for a second revolutionary movement in the wake of President Trump’s first bourgeois revolution?

This is especially puzzling because the American people, it seems, are so thirsty for radical politics. The far Right has gotten so much momentum today precisely because it is radical. Because it is channeling the widespread feeling that the political system is broken and only serves the interests of liberal elites. Because it has appropriated Lenin and the Leninist language of smashing the state and draining the swamp.

Once again, sadly, the Left has been outmaneuvered on its own terrain.

In my view, it is time to reclaim the Hegelian lineage of Lenin and the key idea of self-movement, to take advantage of the smashing of the state machine, and to call for a second social movement to overcome President Trump’s revolution and bring about a new and just society—on the basis of solidarity and cooperation, rather than on hate and exclusion.

The Dialectics of Smashing the State Machine

As I intimated earlier, many on the Left worry that the idea of “smashing the state” is not very dialectical and, thus, too blunt an instrument.

But I think it is important to distinguish “the state” from “the state machine” in Lenin’s politics. It turns out that Lenin had a deeply dialectical relationship to the state. The state was something that he imagined continuing after the second movement—or, in more technical jargon, he believed it would be sublated, not eliminated.

Lenin called for smashing the state “machine,” but at the same time, he also acknowledged that the “state” would continue in a different form, namely through direct mass self-governing by industrial and agricultural workers. What he advocated for was a dialectical transformation of the state that would ultimately lead to its overcoming—the famous references to the state “withering away”—when there was no longer any class conflict in society. And he believed it would wither away eventually because, on his view, the state’s primary function is to maintain and enforce class privilege, but that would eventually evaporate with the elimination of classes.

So the state continues to exist, in Lenin’s view, even after the state machine is smashed—at least until some distant future when there are no classes in society anymore.

Smashing the “state machine” can be distinguished from smashing “the state.”

As Kevin Anderson explains, “The age of imperialism, with its monopoly capitalism and even greater centralized planning, had created what Lenin termed ‘the process of transformation of monopoly capitalism into state-monopoly capitalism,’ which meant a strengthened state machine ruling over the workers.”[13] Lenin specifically referred to “an extraordinary strengthening of the ‘state machine’ and an unprecedented growth in its bureaucratic and military apparatus in connection with the intensification of repressive measures against the proletariat…”[14] Lenin was opposed to working within this type of “state machine” and advocated instead for its destruction. But the state machine was different than the state.

Drawing on Marx’s description of the Paris Commune in his 1871 essay Civil War in France, Lenin advocated for political power to be held in the hands of the soviets—the worker and peasant councils.[15] Lenin aspired to a transformation toward a political condition in which everyone would take on, at times, the responsibilities of the state machine, so that no one would be a pure bureaucrat and the state machinery would not crystalize in any one class. Lenin wrote:

Abolishing the bureaucracy at once, everywhere and completely, is out of the question. It is a utopia. But to smash the old bureaucratic machine at once and to begin immediately to construct a new one that will make possible the gradual abolition of all bureaucracy—this is not a utopia, it is the experience of the Commune, the direct and immediate task of the revolutionary proletariat.[16]

Or, in another passage:

the time is nearing when they [the workers] must act to smash the old state machine, replace it by a new one, and in this way make their political rule the foundation for the socialist reorganization of society.[17]

Or, in another passage that Anderson cites:

The workers, after winning political power, will smash the old bureaucratic apparatus, shatter it to its very foundations, and raze it to the ground; they will replace it by a new one, consisting of the very same workers and other employees, against whose transformation into bureaucrats the measures will at once be taken which were specified in detail by Marx and Engels: (1) not only election, but also recall at any time; (2) pay not to exceed that of a workman; (3) immediate introduction of control by all, so that all may become “bureaucrats” for a time and that, therefore, nobody may be able to become a “bureaucrat”.[18]

A Word of Caution

Now, I do not intend to get bogged down in Leninology, nor in the intricate details of Lenin’s debate with Karl Kautsky or Rosa Luxembourg—any more than I want to get caught up in Steve Bannon’s claim to be Leninist, nor his interpretations of Lenin.

My point is that there is a dialectical nature, and in this sense, a Hegelian dimension to Lenin’s call to smash the “state machine”: it is not pure negativity, nor pure destruction, but instead a call for a different state apparatus. There is self-movement.

And this too resonates today.

Trump’s Smashing of the State

There is no doubt that neither President Trump nor Steve Bannon are calling to simply smash the state. They do not advocate anarchism. They too are transforming the state machine into another state form.

President Trump is smashing the administrative state to create a more concentrated police state. President Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” turned ICE into the largest law enforcement agency in American history and funded new ICE detention facilities to the tune of $45 billion. President Trump has rebuilt the camp at Guantanamo Bay into a massive deportation facility. He has transformed the Department of Defense into the Department of War, has dropped bunker-busting bombs in Iran, and is waging a new and unprecedented military assault on suspected drug-traffickers in international waters. And even with regard to the agencies that he has gutted, such as the Department of Education, President Trump is reconstituting their missions through coercive pay-for-play agreements, such as those with individual law firms, research universities, and foreign countries.

This represents a vision of a robust police state, with masked ICE agents kidnapping persons based on the color of their skin and military personnel policing urban cities. It is also a walled state. It would be far too naïve to suggest that President Trump is simply “smashing the state.” He is instead birthing a police state.

A Second Revolutionary Movement Today

Now, given that President Trump is already dismantling the administrative state, with or without our approval and in the face of little resistance by the Democratic Party, the best strategy for the Left—what I have called elsewhere the “counter-move,” or the jujitsu—is, rather than opposing what he is doing, redirect the force and momentum of his actions towards a progressive agenda, creating more fairness, justice, opportunity for all, especially the working class.

The Left should seize the momentum and push a second revolutionary moment today, as Lenin urged in his April Theses. The time for restoration is over. Bannon the Leninist must be overcome. There needs to be a second self-movement.

What shape should this second social movement take? That, I think, is the most urgent and important question for the Left to address today. It is what the Left needs to figure out most pressingly. And only a handful of political leaders seem to be attuned to this—Bernie Sanders, AOC, Zohran Mamdani. But this is the key question for the Left now.

Violent revolution, like Lenin’s Bolshevik revolution, is out of the question—if for no other reason than that the far Right is the only violent revolutionary force in American society today and is armed to the teeth. The far Right is far more likely to engage in armed revolution than any other faction of American society, and more likely to win. So violence is off the table.

What then could a second uprising look like?

I think it would be a massive movement for solidarity and cooperation in the face of the hate, exclusion, and violence that is spewing forth in the Trump administration—from the masked ICE agents, to the summary executions in international waters, to the military flooding our urban streets.

What we need now is a massive counter-movement showering solidarity and cooperation throughout every facet of life. This would include universal healthcare as in most of our peer countries. Job training programs for everyone to retool in the age of artificial intelligence. Mental health care for all. Promoting worker cooperatives, food coops, and housing cooperatives for affordable housing. It would mean creating organizations that prioritize all the stakeholders, communities, and the environment, rather than simply the investors. These ideas—and more—are what we need to focus on now, immediately, to set off a second wave, a chain reaction, a second revolutionary progressive self-movement, to overcome the Trump revolution.

Never Let A Serious Crisis Go To Waste

The expression should be familiar, even if it is usually associate with the Right. You will recall that Philip Mirowski used it in the title of his eponymous book to describe how neoliberals took advantage of the Great Recession to further their agenda of free market liberalism. Naomi Klein drew on the idea to describe Chicago neocons in her book The Shock Doctrine. And even though the expression is often attributed to Winston Churchill, it is clear that it has been appropriated again and again by the far Right. It is Bannon’s key strategy.

Well, here too, there is a connection to Lenin. In his writings on the Irish popular uprisings, which he considered premature, Lenin nonetheless praised the revolts for contributing to the self-movement of history. “The dialectics of history are such that small nations, powerless as an independent factor in the struggle against imperialism, play a part as one of the ferments, one of the bacilli, which help the real anti-imperialist force, the socialist proletariat, to make its appearance on the scene.”[19] (Lenin could hardly have sounded more Hegelian!) And after praising the Irish uprising, Lenin adds:

We would be very poor revolutionaries if … we did not know how to utilise every popular movement against every single disaster imperialism brings in order to intensify and extend the crisis.[20]

It is time, again, for the Left to seize the momentum and not let this crisis go to waste. The stakes are too high.

This essay is part of the Hegel 13/13 public seminars. Read and learn about the Hegel 13/13 seminars, and watch and listen to the upcoming sessions, here https://hegel1313.law.columbia.edu

The essay is also cross posted on Substack here: https://bernardharcourt.substack.com/p/what-is-to-be-done-about-the-radical

Notes

[1] Ronald Radosh, “Steve Bannon, Trump’s Top Guy, Told Me He Was ‘a Leninist’”, The Daily Beast, Aug. 22 2016, available at https://www.thedailybeast.com/steve-bannon-trumps-top-guy-told-me-he-was-a-leninist/

[2] Christopher Rufo speaking on Michael Barbaro, host, “The Conservative Activist Pushing Trump to Attack U.S. Colleges,” The Daily (podcast), April 11, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/11/podcasts/the-daily/christopher-rufo-dei-critical-race-theory.html.

[3] Lenin, The State and Revolution, in Collected Works, Volume 25, p. 381-492; p. 22 here https://www.marxists.org/ebooks/lenin/state-and-revolution.pdf (emphasis added).

[4] Lenin, The State and Revolution, in Collected Works, Volume 25, p. 381-492; p. 22 here https://www.marxists.org/ebooks/lenin/state-and-revolution.pdf

[5] Anderson, Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism, p. 231.

[6] Lenin, Conspectus of Hegel’s Science of Logic, in Volume 38, at p. 180.

[7] Lenin, Conspectus of Hegel’s Science of Logic, at p. 141

[8] Lenin, On the Question of Dialectics (1915)

[9] Lenin, On the Question of Dialectics (1915)

[10] Lenin, On the Question of Dialectics (1915)

[11] Lenin, On the Question of Dialectics (1915)

[12] Panel Study of the MAGA Movement by Rachel M. Blum, Assistant Professor, University of Oklahoma, and Christopher Sebastian Parker, Professor, University of Washington, Demographics & Group Affinities, available at https://sites.uw.edu/magastudy/demographics-group-affinities/.

[13] Anderson, Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism, p. 231.

[14] Lenin, The State and Revolution, in Collected Works, Volume 25, at p. 415, quoted in Anderson, at p. 231.

[15] Anderson, Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism, p. 232.

[16] Lenin, The State and Revolution, at p. 36 online here: https://www.marxists.org/ebooks/lenin/state-and-revolution.pdf

[17] Lenin, The State and Revolution, at p. 83 online here: https://www.marxists.org/ebooks/lenin/state-and-revolution.pdf

[18] Anderson, Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism, p. 233, quoting Lenin, The State and Revolution, in Collected Works, Volume 25, at p. 486.

[19] Lenin, The Discussion on Self-Determination Summed Up (1916)

[20] Lenin, The Discussion on Self-Determination Summed Up (1916)