By Bernard E. Harcourt

Abstract:

In this essay, “Hegel and the Heritage Foundation,” I sketch the family resemblances between the systematic thought of G.W.F. Hegel and the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025. I demonstrate that they both anchor their political viewpoints in a similar starting place, namely the traditional family (a man and a woman and their children) and the ownership of property. The family and property serve as the grounding that leads Hegel to justify the rule of an autocrat (the sovereignty of a hereditary constitutional monarch) and the Heritage Foundation to justify the dismantling of the administrative state. In the essay, I then show how to design an entirely different political project that, first, starts from existing interpersonal relations and all the acts of cooperation that make our lives possible, and, second, leads to a society of democratic self-governance, solidarity, cooperation, and equal thriving for all people.

“It is not difficult to see that ours is a birth-time and a period of transition to a new era.”

— Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, “Preface,” p. 6.

These are Hegelian times. The spirit of our epoch is changing. There is a shift in the American mindset, a distinct and noticeable turn to the Right.

We are living through a formidable historical transformation—right here, right now. A modern counterrevolution has snapped to pieces liberal institutions, the former ramparts of the neoliberal establishment. Political liberalism has proven impotent, especially now in the face of a commanding rightwing populism across the globe. One by one, the bulwarks of liberalism are being toppled over: the legal establishment, the academe, the media, the Democratic Party. They are being burst apart by a wave of nationalist populist sentiment.

A conservative will to power is seizing the moment. Far-right coalitions are ascending. But they are deeply unstable and likely to give way to a radically new political landscape that is practically unpredictable at this point, unknowable.

We could be witnessing the rise of global fascism, the consolidation of ethno-nationalist enclaves, or the emergence of political theocracies—or perhaps, the birth of new Left alternatives.

One thing is for sure: we have entered a new historical era. The interregnum we all have been speaking about is coming to an end. Something new is about to emerge.

These are Hegelian times.

And in this moment of historical transformation, there is an opening for a new social movement of cooperation, mutual aid, and solidarity among the vast majority of people—the great number of human beings who are compassionate, who care about others, and who tend to those in need. There is an opportunity for a new progressive movement, for equal dignity and human emancipation, for mutualism and respect, for a new politics that seeks to achieve for everyone their fullest flourishing regardless of race, gender, creed, nationality or mind-set.

One can already hear and feel the rumblings. Protesters in Los Angeles took on the Goliath of masked ICE agents and deputized National Guard members, without fear—and Chicagoans are gearing up. Bernie Sanders and AOC stormed the country on their Fighting Oligarchy Tour. Zohran Mamdani triumphed over his centrist Democratic opponents in the mayoral primaries of New York City, and brought out troves of young voters. There is a new spirit awakening across the country. A new spirit of care, compassion, cooperation, and solidarity.

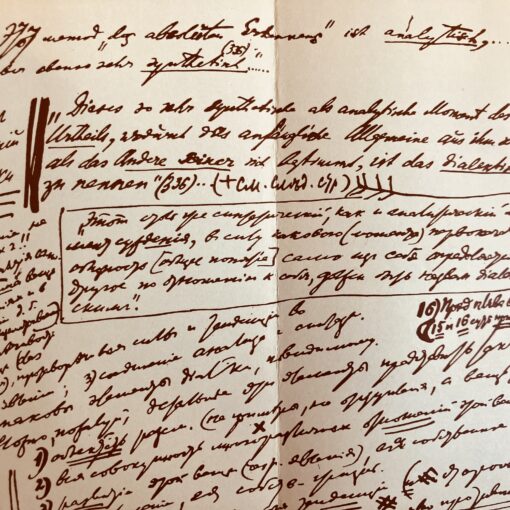

Yes, these are Hegelian times. And in moments like these, new philosophies and practices have so often emerged from a sharp confrontation with ideas from the past. I am thinking especially of ideas, concepts, and methods from the Hegelian toolkit. Whether it was Marx in the nineteenth century turning the Phenomenology of Spirit on its head, or Lenin closely annotating The Science of Logic, or C.L.R. James transforming the dialectic into a tool for decolonization, or Frantz Fanon or Jean-Paul Sartre inverting the master-slave dialectic, or Judith Butler turning subjectivity into desire, so many of the major contributions to critique and praxis in the past two centuries were born from an antagonistic struggle with Hegel’s thought.

To confront Hegel again

It is time then, once again, to return to Hegel, not to think with him, but rather, as it has so often been more productive, to think against him again. It is time for another round of agonistic confrontations with Hegel’s writings.

Now, let there be no doubt. Hegel was deeply problematic in his politics. He was a radical thinker, to be sure. Not conservative in the traditional sense of wanting a return to a past; no, he understood the dynamism of political consciousness and the need to move forward, constantly. But his politics were problematic—no matter how much thinkers like Herbert Marcuse, in Reason and Revolution, or others would try to recuperate him.[1] Of this, there can be no question: “Our objectively appointed end and so our ethical duty is to enter the married state,” Hegel states in his Principles of the Philosophy of Law (1820).[2] “The sovereignty of the people,” he adds, “is one of the confused notions based on the wild idea of the ‘people.’”[3] As Marx would retort, “The confused notions and the wild idea are only here on Hegel’s pages.”[4] And let’s not even discuss how Hegel relegated African culture to prehistory and disparaged Africans, or relegated women to the private, domestic sphere of the household.

Yes, indeed, there were Right-leaning passages in Hegel’s writings. But we do not return to Hegel to embrace his politics. Nor to recuperate him. Nor, subliminally or ideologically, to turn attention away from other more radical thinkers, as Louis Althusser had so presciently warned us not to do.[5] No, we turn to Hegel to confront his ideas and challenge his method and, in the process, to dig and excavate and invent new paths forward toward a horizon of solidarity and cooperation. We confront and draw from the well of his spirit, in a contrarian way.

The goal: to explore the past inversions of Hegel that have been so productive for the Left, in order to rethink the rightward shift going on today and invent a new and alternative Left politics for tomorrow. Not just to reread Hegel. Nor simply to reread Marx, Lenin, James, Marcuse, Kojève, Sartre, Fanon, Foucault, Butler, and others on Hegel. But to study their Hegelian “acrobatics,” as Homi Bhabha suggests, in order to understand and respond, to resist, displace, and help forge a new alternative to the far-Right today.

Let us learn from the way that Marx stood the Hegelian dialectic on its head to develop such a powerful and influential world-historic critique of capitalism. “The mystification which the dialectic suffers in Hegel’s hands,” Marx explains in Capital, “by no means prevents him from being the first to present its general forms of motion in a comprehensive and conscious manner.” Marx continues, “It must be inverted, in order to discover the rational kernel within the mystical shell.”[6] Similarly, let us now learn from the way that Lenin mined Hegel’s Science of Logic to sharpen his critique of imperialism, or how Marcuse sought to make a “contribution to the revival, not of Hegel, but of the power of negative thinking.”[7] Or how Fanon, in his provocative chapter on “Le nègre et Hegel” (“The Negro and Hegel”) in Black Skin, White Masks, reimagines Hegel’s master-slave dialectic to inspire anti-colonial action and revolt.[8]

These times are urgent and call for creativity and rethinking. The ideas of the past are just that, past. But the past confrontations with those ideas can serve as a vital resource to jumpstart a new political program, a new vision, a new horizon. Especially when we experiment with them, play with them, push them, twist, turn and distort them—the way that Foucault plied the thought of writers whom he admired, the way in his own words, he used them, deformed them, made them “groan and protest.”[9]

Let’s see how brilliant thinkers made Hegel groan and protest, so that we too can rethink our present crisis of authoritarianism. The times could not be more urgent.

So let’s start right now. Let’s experiment. Let’s see if we can prefigure what we might be able to do confronting Hegel again. But this time, with the present historical conjuncture in mind.

Family, civil society, State

The Heritage Foundation, the conservative think tank propelling a rightwing movement in America today, bases its worldview and political program on the trilogy that Hegel made famous in his Principles of the Philosophy of Law: family, community, and State.

First, the family, the very source and core of the Heritage Foundation’s worldview. The Foundation embraces a Christian, faith-based view of the family as the union of a man and a woman for purposes of procreation. Marriage is the central institution, but marriage between a man and woman for purposes of raising children in a nuclear family. Marriage between a man and woman is viewed as a moral imperative and touchstone. Any deviation from that norm, they view as unnatural. What liberal governments have been doing, they claim—the harm they have been doing, that is—is “to replace people’s natural loves and loyalties with unnatural ones.”[10] And so the very first promise the Foundation articulates in Project 2025 is to “restore the family as the centerpiece of American life and protect our children.”[11]

Second, civil society. The family should be mediated not by the government, but by the community—by the church and schools. The Heritage Foundation speaks of these in terms of community at times, at other times in terms of “the institutions of American civil society.”[12] These institutions are the ones that function as and make up, in the Hegelian topography, “civil society,” even if, at times, the Heritage Foundation makes it sound more like Ferdinand Tönnies’ Gemeinschaft (community) than Gesellschaft (civil society). Either way, the Heritage Foundation builds a clear demarcation, a wall really, between civil society and State. It emphasizes that the mediating function must not be conducted by the State, but rather by the community. “These are the mediating institutions that serve as the building blocks of any healthy society,” Kevin D. Roberts, the President of the Heritage Foundation, writes: “Marriage. Family. Work. Church. School. Volunteering.” He adds, emphasizing: “The name real people give to the things we do together is community, not government.”[13]

Third, then, the State. The Heritage Foundation proposes—in fact, militates for—a streamlined vision of government, without its administrative apparatus or bureaucracy, without the administrative state, and limited to the core idea of popular sovereignty expressed through the legislature. The State represents, simply, the will of the people: democratic self-determination based primarily on Article I of the U.S. Constitution—Congressional power. The Heritage Foundation endorses the unified executive theory (“UET”): all executive functions should ultimately report to and be accountable to the President. In the short term, the Foundation is enthusiastic about the president single-handedly dismantling the administrative state—firing all the federal workers, shuttering departments, and dismantling agencies; but in the long-term, democratic self-determination operates through the legislature. This goes hand-in-hand with a preference for small government and laissez-faire economic policies.

What follows is radical. The innate concepts of natural and unnatural, for instance, lead to forms of fundamentalism regarding the family and traditional male-female relations. The Heritage Foundation wants to excise from every federal rule and regulation terms like sexual orientation or gender identity—or even the word “gender” insofar as it might challenge a heterosexual or patriarchal norm. Kevin Roberts writes:

The next conservative President must make the institutions of American civil society hard targets for woke culture warriors. This starts with deleting the terms sexual orientation and gender identity (“SOGI”), diversity, equity, and inclusion (“DEI”), gender, gender equality, gender equity, gender awareness, gender-sensitive, abortion, reproductive health, reproductive rights, and any other term used to deprive Americans of their First Amendment rights out of every federal rule, agency regulation, contract, grant, regulation, and piece of legislation that exists.[14]

To strike the term “gender” from every federal text, that is indeed radical, and it flows seamlessly from the trilogy of family, civil society, and State. It flows seamlessly from the Hegelian trilogy, that is.

Now, to be sure, the content is not necessarily Hegelian. In fact, in terms of institutional design, it is much closer to Marx than to Hegel: while Hegel favored a constitutional monarchy, Marx favored instead democratic, popular-based governance. Marx would have been opposed to elite policymakers governing, just as the Heritage Foundation is opposed to the administrative state—which, for Marx, would have been the equivalent of the Prussian bureaucracy. And there are other elements that are more proximate to Marx as well, such as the relationship between man and nature (at least, setting aside the newer scholarship on the Late Marx of Kohei Saito, Marcello Musto, and others). The Heritage Foundation embrace a nineteenth century view of that relationship: man should control nature, especially natural resources. On its view, the U.S. should exploit its dominance of energy resources. It places its faith in human resilience and creativity.[15] It even borrows from the “turn-on-its-head” logic of Marx, arguing that it is environmentalists who have turned things around: “They would stand human affairs on their head, regarding human activity itself as fundamentally a threat to be sacrificed to the god of nature.”[16]

No, the point is not that the Heritage Foundation is advancing a worldview that resembled that of Hegel. Not at all. But the structure of the argument, the relation between family, civil society, and State is sufficiently adjacent to the Hegelian system that it could prove useful, here, to draw on the different ways that thinkers have inverted Hegel to invent their own philosophies. How can we borrow here, or learn from, or get inspired by the way that C.L.R. James, or Frantz Fanon, or others used Hegelian ideas as a foil. How can we write, in effect, the missing critique and commentaries to paragraphs 142-260 of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right in such a way that it might give birth to a new political vision and program?

Ab initio: Where do we start?

One of the most important insights from the centuries-long confrontation with Hegel is the importance of determining where to start—where to begin the dialectical (or anti-dialectical, or counter-dialectical) movement.[17] As Marx demonstrated so powerfully in his early drafts (Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy and the Grundrisse) and book (Capital, Volume 1), the starting point is key: money, or capital, or the commodity. The difference between C-M-C and M-C-M is pivotal. The decision whether to begin with the chapter on money or the chapter on capital, or with commodities, and how those choices would invert the idealism of Hegel and ground a new materialism, are key moments in the confrontation with Hegelian ideas.

Gilles Deleuze—perhaps the most anti-Hegelian thinker, the one who entirely displaced the dialectic and contradiction with concepts of difference and repetition—and Félix Guattari rebelled against the idea of starting with the family. That was the entire point of their Anti-Oedipus in 1972: to critique the fetishization of the bourgeois family and how the Freudian oedipal complex serves to redirect all of the bourgeois libido back into the nuclear family.

Now, we know where both Hegel and the Heritage Foundation begin. With regard to ethical life, Hegel begins his Principles of the Philosophy of Law with the family. So does Kevin Roberts at the Heritage Foundation.

The question for us, now, then, is whether we should start with the family as well, today? Should our analysis start there? That is the question this first confrontation raises. Do we ground everything on a first principle to “restore the family as the centerpiece of American life and protect our children.”[18]

And the first point, of course, is that the American family is far more rich and diversified than the image of it that the Heritage Foundation projects. Today, it includes and can be comprised of two mothers and their children, or two fathers, or a parent and grandparents, or unmarried companions—there is today a far wider array of possibilities for raising children. And what matters most is the love and affection and support in the family unit, not the form of the heterosexual couple. On that point, I am prepared to simply disagree without further elaboration with the Heritage Foundation and proponents of a conservative traditional family viewpoint. What matters, I would argue, is that there is love and understanding in the family unit, no strife nor domestic abuse, and support from the surrounding community. That, I think, is the easy part.

But on the question of where to start the analysis, it makes no more sense to start the political analysis with the traditional family and the parental relationship to children than it does to start with Robinson Crusoe—or for that matter, with Robinson Crusoe with or without his man Friday. The family, the state of nature, why start there? And what work does it do to start there?

One answer is that it bakes into the analysis natural forms of exclusion: the traditional family unit is the biological or adoptive unit, and it naturally excludes those outside the family unit. It reinforces the family bias or intuition, and turns into a tautology the conservative mantra concerning the order of love, of ordo amoris, captured most recently by J.D. Vance, who endorsed in a TV interview the “Christian concept that you love your family, and then you love your neighbor, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens in your own country, and then, after that, you can focus and prioritize the rest of the world.”[19]

Neither the individual in isolation, nor the traditional family are the right place to start for a progressive politics. A leftist politics would need to start instead with the acts of cooperation that bring people together into a community and make people work productively with each other, to assist each other, provide support and mutual aid. In effect, a leftist politics would need to start with the community.

Now, to be sure, there can be quite a few exclusions built into the community, and perhaps that would be the first set of contradictions to address: How have communities in the past segregated others, or red-lined or excluded others. There is no naturalness to the concept of community, any more than there is to the traditional family.

This means that the community must be regulated properly—racial covenants on property need to be prohibited; segregation along racial or religious lines needs to be prevented; etc. In this way, the abstract community needs to be overcome by means of regulations of civil society and State.

But politically, the place to start could be the community, the collectivity—perhaps something closer to the “fused group” that Sartre described in the Critique of Dialectical Reason.

This calls for a rereading and renewed confrontation with Hegel’s discussion of the family and civil society in the Philosophy of Law—a session that we will hold first as we begin with the 1843 manuscripts.

Our embedded lives, a starting point

But let’s go further down this path for now—to experiment or prefigure the work of Hegel 13/13.

In the same way in which privileging the traditional family introduces assumptions and exclusions into the political theory, the simple concept of community or collectivity may also be far too abstract, because the definition of the community, or of the collectivity, is itself loaded with values. Which community do we privilege? Faith communities? Or educational communities?

No single one, actually. To speak of community or collectivity is to gesture at something else, something different. What we are aiming at when we refer to community is one’s surroundings, one’s existing real environs and all of the attachments one has to other people in one’s current existence.

In effect, the place to start, really, is in the embeddedness of our lives and our lived experience, and to include all of one’s relations to others. These include colleagues and co-workers. They include neighbors and friends from high school, and grade school, friends from college, the people who we speak with and write to. These include the cashier at the grocery store and the other residents in your housing coop. They include one’s boss and the people that you report to, or the people that you work with, or the people who might report to you. They include the people you serve or care for, or the inverse, the maintenance person at your work, the crosswalk safety guard. The children you teach or the teachers of your children. It includes all those other people who you come into contact on a daily basis, or weekly basis, or monthly basis. People you have befriended, with whom you accidentally struck up a conversation, who you communicate with in the street. It includes the prison guard or the warden or fellow prisoners. Wherever you are, whoever you are, you are surrounded by other people. The community is them.

The description here is intended to be neutral in terms of socio-economic relations. I have listed several interpersonal relations, everyone has these, whether they are at the one extreme or the other of the socioeconomic ladder. I am referring to the people who you encounter every day, every week, who you know, whose names you know. That is where we have to start the political analysis. Of course, it includes your partner, if you have one, or your spouse, if you have one, or your children, if you have children, or your parents, if your parents are still alive, or your guardian, or adoptive parents, or the people who raised you, as well as your extended family. Naturally, they all form part of your community, but they do not define or limit it. Your spouse does not define the starting point. They contribute to the rich interpersonal surroundings that you have, they are part of the surroundings that allow you to live and thrive, and at times falter, but they do not define it.

For the most part, the community that surrounds us is formed by the acts of cooperation with people surrounding us who make our lives possible—who make it possible for us to live and thrive, through their acts of exchange, of giving, of helping and collaborating. All those interactions are, again for the most part, cooperative interactions, whereby you are providing things to others, and others are providing things to you. It may be a conversation. It may be a salary. It may be caring for someone. It may be fixing something, or replacing something, or exchanging something. It may be consuming something together, providing a service to someone, or waiting their table. These are all cooperative acts—cooperative in the sense that we are engaged in interpersonal interactions that are intended to benefit oneself and others.

Of course, they’re all laced with coercion. There are relations of power that traverse them through and through. Many of the interactions may not be fully voluntary. If you had your druthers, maybe you would not be doing this or that. Maybe you would not be befriending a colleague or a superior. Yes, of course, the relations are fraught, always fraught, but they are acts of collaboration nonetheless. And those relations of power infect family relations as well. In the family setting, there can be a lot of coercion and obligation and guilt.

But the point is, to limit or even begin our analysis with the traditional family is, well, preposterous. Many people don’t have spouses. Many people don’t have partners. Many people live alone. Many people don’t have children. Many people raise other people’s children. In wealthy families, children are raised by nannies. Focusing on the traditional nuclear family inevitably results in logical absurdities, as in the idea of there being a moral obligation to get married and to have children—as in Hegel’s Philosophy of Right or in the Heritage Foundation worldview.

Privileging the family inevitably leads to the idea of family obligations that do not reflect reality and that are not the only or the most central ties that one may have, even if they are ones that might bring so much joy for some. So the place to begin is in our deeply embedded social relations, in the collectivity that surrounds us, in our real situated space, in our surroundings. And it turns out that those are formed predominantly by acts of cooperation with the people who surround us.

A historical grounding

And it makes sense to begin the political analysis here, not simply because it is the real, the concrete, but also because it grounds the analysis historically. When we start with our actual, real surroundings, we are in the present historical moment. Our surroundings are historically shaped. They reflect the economic system that we live in. They reflect the social relations of the times. They are shaped by the progressions and shifts of history.

To analyze our really existing surroundings is necessarily a historically defined project. It is necessarily a historically situated project. A historically contextualized project.

We are at the heart of the present historical conjuncture when we try to understand our own relations and our surroundings and the communities that we form part of as the focus of inquiry. The analysis does not then need to be historicized. The analysis is necessarily located in a specific moment, historically.

By contrast, the family as an abstract concept is not historicized. Certainly not in the way in which it is presented in the Heritage Foundation or in Hegel’s work. There, it is an abstract concept, far removed from families today. It is formalized. It is a universal of some kind, but it is completely unconnected to reality.

How do we historicize? The most important aspect of Marx’s work is to locate everything in its historical moment, especially in terms of global forces, modes of production, and economic relations but we can expand that, with Stuart Hall and others, to cultural forces as well. By situating ourselves in the present and acknowledging the power relations that shape our present experience, we have automatically satisfied the requirement of historicization; we remain conscious of all the ways in which our social relations are shaped by current modes of production and exchange and broader economic and cultural forces.

Casting the die

The broader point is that there is no neutral place to start the political analysis. This is something that Foucault emphasized—but also elided by always jumping mid-stream into discourse.

On the one hand, Foucault underscored that there is no way to establish reality in a neutral objective way, because one must always choose which facts to privilege, which facts to start with, which facts to discuss and highlight. There may well be facts that can be verified. There may be accurate, correct facts. But even so, what matters more are the interpretations we make of those facts and the choices of which ones to discuss. And here, there is no neutral place. Where to start the discussion is a matter of choice. It is political.

On the other hand, aware of this, Foucault preferred not to choose.

I wish I could have slipped surreptitiously into this discourse which I must present today, and into the ones I shall have to give here, perhaps for many years to come. I should have preferred to be enveloped by speech, and carried away well beyond all possible beginnings, rather than have to begin it myself. I should have preferred to become aware that a nameless voice was already speaking long before me, so that I should only have needed to join in, to continue the sentence it had started and lodge myself, without really being noticed, in its interstices, as if it had signalled to me by pausing, for an instant, in suspense. Thus there would be no beginning, and instead of being the one from whom discourse proceeded, I should be at the mercy of its chance unfolding, a slender gap, the point of its possible disappearance.[20]

Quoting Samuel Beckett, perhaps my favorite author, Foucault yearned for that someone else who had already started the conversation, made the choice, and prodded us along with the famous words: “You must go on, I can’t go on, you must go on, I’ll go on, you must say words, as long as there are any, until they find me, until they say me, strange pain, strange sin, you must go on, perhaps it’s done already, perhaps they have said me already, perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story, that would surprise me, if it opens.”[21]

And Foucault goes on:

I think a good many people have a similar desire to be freed from the obligation to begin, a similar desire to be on the other side of discourse from the outset, without having to consider from the outside what might be strange, frightening, and perhaps maleficent about it. […] Desire says: “I should not like to have to enter this risky order of discourse; I should not like to be involved in its peremptoriness and decisiveness; I should like it to be all around me like a calm, deep transparence, infinitely open, where others would fit in with my expectations, and from which truths would emerge one by one; I should only have to let myself be carried, within it and by it, like a happy wreck.”[22]

I can understand the desire to want to start in the middle of discourse. I can understand the yearning to not to have to begin. And I can appreciate the almost overwhelming role of discourse in shaping what we might have to say—almost determining what we say and how we say it.

But despite that righteous insight and intuition, we must always begin somewhere. And where we begin is equally determinative of what we will say.

This is so clear from reconsidering Marx’s different attempts at beginning his study of political economy—of starting the work. Marx placed the commodity first in his first published attempt in 1859, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. He opens the book, the preface, in the following terms: “I examine the system of bourgeois economy in the following order: capital, landed property, wage-labour; the State, foreign trade, world market.”[23] The progression had Hegelian overtones. The starting place was capital, the commodity.

Two years earlier, in the Grundrisse, his notebooks from 1857, Marx started instead with the chapter on money. And in the introduction to the Grundrisse, he starts even elsewhere: “The object before us, to begin with, material production.”[24] That required, first, confronting eighteenth century ideas, or the “illusion”[25] as he calls it, of the independent individual, because that of course is where all the others began, from Smith and Ricardo to Rousseau to Defoe in his Robinson Crusoe, to Bastiat, Carey, and Proudhon.[26] By contrast to these, who focus on the independent, autonomous, abstract individual, Marx write, “Individuals producing in society—hence socially determined individual production—is, of course, the point of departure.”[27]

Ten years later, in Capital Volume 1, it is with the capitalist commodity that Marx opens: “The wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails,” Marx writes, “appears as an ‘immense collection of commodities’; the individual commodity appears as its elementary form.”[28] And so, he states, “Our investigation therefore begins with the analysis of the commodity.”[29] And so, like a scientist studying cells in a microscope, but using abstraction instead, Marx tells us, the place to start is with the economic cell-forms of the commodity form.[30] Roman Rosdolsky, in his meticulous recounting of the stepwise progression from the Grundrisse to Capital, traced all of these beginnings, charted their interrelationships, and documented how they gave birth to the different plans for the complete volumes of Capital, all in his early book The Making of Marx’s Capital (1968).[31]

“Beginnings are always difficult in all sciences,” Marx writes on the first page of his preface to the first edition.[32] Difficult, I would say, but telling. Or perhaps more, formative. The place to start an analysis, a dialectic, a study inevitably anchors a political theory.

Hegel begins his analysis of law in the first part of his Principles of the Philosophy of Law—which is intended to trace the long history of how brute individual free will develops and transforms into a robust form of liberty (or ethical life) in the modern state—again, he begins his analysis with property law. It is private property, the ownership and possession of things, that grounds the analysis, that is the first instantiation of a person’s liberty, that is the person’s first consciousness and realization of having an immediate free will. It grounds the analysis in the sense that it then forms the material substratum for his discussion of contract law as a higher form of recognition of one’s free will—which is important. “Contract,” he explains there, “presupposes that the parties entering it recognize each other as persons and property owners. It … contains and presupposes from the start the moment of recognition.”[33]

As law professors, we constantly debate where to start a legal education, which is to say, where to start legal analysis. At Columbia Law School, we start the study of law with what we call “Legal Methods,” a special class designed by American Legal Realists like Karl Llewellyn in mid-twentieth century, to expose and teach entering students what the law is. We then plunge the students in a mandatory curriculum for the first year that begins with torts, civil procedure, contracts, constitutional law, criminal law, and property law. The sequencing matters. The place to begin matters.

By starting with private property in the Principles of the Philosophy of Law, by grounding the analysis in property, Hegel has thrown the dice. He has inserted the analysis of free will into property ownership—something that was not necessary beforehand. The die, now, is cast. But it need not have been that way.

Similarly, when Hegel decides to discuss, in the section on “Civil Society,” court administration, the tribunals, and the police—the police both narrowly and more broadly in terms of public authority or what was called Polizeiwissenschaft at the time, or what he refers to as “Die polizeiliche Vorsorge”[34] or “policing precautions”—bref, when he decides to discuss the courts and the police first as part of “civil society,” rather than in the section on “The State,” Hegel has thrown the dice again.

To be sure, those two institutions—the courts and the police—mediate between the particularity of the individual and the universality of the State. They mediate between the self-interests of people in society and their conflicts with others. But they are, through and through, institutions of the State. They are the right hand of the State, as Bourdieu would say, the right fist of the State. They represent the most direct and concrete manifestations of the State—what we, as citizens, are most likely to first encounter of the State.

Locating the police and the tribunals first in civil society is, on my view, patently wrong, but prescient in its error. It is brilliant in being so wrong. Because it reveals that those are the State institutions that, invisibly, manage the poor class—and in that sense, are often hidden in plain sight in civil society.

Walk into any courthouse in any county around this country—they are open to the public—ask the officer at the security for the arraignments part (where the local judges are processing the first appearances of people who have been arrested and detained by the police), and you will witness a procession of impoverished men of color, the poor and downtrodden, the outcasts of society, hands cuffed behind their backs, in dirty street clothes, being processed by the system. Black and brown men shuffle into the well from the holding cell, dazed. These men are the “rabble,” as Hegel called them—and as he predicted, it would grow in size with the growing inequality in economic exchange. That’s ¶ 243 of the Philosophy of Law, with its natural consequence of colonization (¶ 246).

Placing the police and tribunals within “civil society” and not, more directly or first within the “State,” sanitizes the management of the poor and removes it from view. It renders it apolitical. Instead of the tribunals and police being understood and perceived as the coercive arm of the state, they are first presented as a mechanism to deal with intra-social conflict—conflict among members of civil society. What an illusion!

In New York—the city but also the state—it is “the people” who are acting to create order and punish the rabble. Yes, the “people” is the body, civil society. In court, all cases are called out “The People versus so-and-so.” The people are on the caption of every prosecution. It is not “the State” that is prosecuting or enforcing the law. It is not “the State” in the caption. It is not “the State” who is seeking to imprison the accused. It is rather “the people.” The prosecutor speaks as “the people.” The Court defers to “the people.” “The people” seek justice and a return to civil order.

The fact that Hegel would place the police and tribunals in the section on civil society is a red flag that begs the question: What is civil society?

Shall we build a new framework?

So, starting the analysis with our embedded lives in the community and collectivity, rather than the family, is a first act of defiance, a first inversion of Hegel, that puts the analysis back on its head.

More broadly, though, it raises the question whether it makes sense, starting from there, to build a new system. Not, like Foucault, to plunge mid-stream into discourse—even if that is, in a sense, inevitable. But to, more deliberately, aim to build a new and better system than the one that Hegel left us.

I say this with hesitation as someone who has critiqued systems analysis and system’s thinking. In an article titled The Systems Fallacy: A Genealogy and Critique of Public Policy and Cost-Benefit Analysis, published in 2018 in the Journal of Legal Studies, I demonstrated how the assumptions embedded in any systems analysis bakes values into the outcomes.[35] So I am a critic of systems thought when it is presented as neutral and objective. Foucault as well, on my reading. In fact, Foucault’s chair at the Collège de France was entitled “The History of Systems of Thought”—Histoire des systèmes de pensée. And surely Hegel’s thought should be understood as a system, as systemic. But given my hesitations about the concept of a system, perhaps I should be speaking instead about a new framework, or approach, or vision. A new method. A new paradigm.

The framework that Marx bequeathed us no longer functions the way it did in the past—as a system, really. For decades now, the Left without Marx, or without his system, has been struggling. There has been a loss of gravitational force. A loss of cohesion. Many on the Left still identify as Marxists; but far more, even people who would call themselves Socialist or Democratic Socialist would not self-identify as Marxists. And it is hard to imagine a return to Marx’s system today, given the rise of identity politics on the Left as well as the fundamental transformation of capital in a globalized and financialized time.

So the burning question is whether the Left needs a new framework, and, if so, where would that new approach begin. Certainly not with the traditional nuclear family as in Hegel’s Principles of the Philosophy of Law, or in Project 2025.

In the end, there is no apolitical place to start the analysis. Starting with the traditional family is a choice. Starting with the school or place of worship would be a choice. But what I have tried to argue is that the analysis should begin right where we are, with our real situation and the actual experience of our embedded lives: our relations to others, acts of cooperation and exchange, daily routines. Starting there would ground the analysis in our real situatedness, the web of social relations that surround us. And shifting the initial focus from the family to the broader community ties underscores the importance of grounding theory in our real, historically situated surroundings given that our social relations extend far beyond the family to our colleagues, neighbors, and others we interact with daily.

On Liberty

But there is more. Grounding the analysis in our real, actual web of social interactions and cooperative acts has the additional advantage that it reveals the ways in which we are situated within webs of relations—social relations, power relations, unneighborly and cooperative relations—that constitute the dense regulatory network that we live in. It has the added advantage of giving us insight into what freedom might be.

Liberty is not really being free of those interpersonal relations. It is not living autonomously, alone, independently, or simply making choices based on our own self-determination. Liberty is not being left alone. Instead, liberty is having our social surroundings organized in such a way as to allow oneself and others to thrive. Liberty concerns the proper regulation of one’s surroundings.

In this sense, freedom is not what the Heritage Foundation has in mind, namely a small government that does not interfere in the economy. That is beside the point. A possible outcome masquerading as a philosophical principle. Freedom is a regulatory form—including government regulation—that allows everyone in society to flourish to their maximum capability. It is a framework of regulation that does not privilege some over others.

The ambition should not be to be left alone, but rather to live in a social and political environment that allows everyone to thrive equally. I tend to think that the notion of thriving equally includes being part of the decision-making process in all the spheres of one’s life, not just in the voting context during elections, but also in context of one’s housing, one’s consumption, one’s workplace. I tend to think that full democratic participation across every aspect of one’s life guarantees or assures that the notion of thriving, of doing well, is not overly determined by particular elites. If we have a democratic vote in every aspect of our lives—in the workplace, in a housing coop, at the food cooperative—then we get to participate in what it means to thrive. And that may be the most important thing. Everyone should have a say in what it means to thrive, to develop to one’s full potential. The key is to make it possible to live freely, surrounded by others who are thriving, to develop one’s own capacities to their utmost.

This is very far from concentrating our free will into the sovereignty of a hereditary constitutional monarch, which is where Hegel landed, but nevertheless, some of you will notice a Hegelian ring to these thoughts on liberty.

Onwards to Hegel 13/13!

Watch the upcoming Hegel 13/13 Seminars here: https://hegel1313.law.columbia.edu/

We are also on Substack now here: https://substack.com/@bernardharcourt

Notes

[1] Herbert Marcuse, Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory (Boston: Beacon Press, 1960 [1941]); see also Herbert Marcuse, Hegel’s Ontology and the Theory of Historicity, trans. Seyla Benhabib (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987 [1932]).

[2] Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, trans. T.M. Knox (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1945 [1942]), ¶ 162 Remark, p. 111; see also Id. at ¶ 167 Remark, p. 115 (“Marriage, and especially monogamy, is one of the absolute principles on which the ethical life of a community depends”).

[3] Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, ¶ 279 Remark, p. 182-183.

[4] Karl Marx, Critique of Hegel’s “Philosophy of Right,” trans. Annette Jolin and Joseph O’Malley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), p. 28.

[5] Louis Althusser, « Le retour à Hegel. Dernier mot du révisionnisme universitaire » [1950], p. 243-260, in Écrits philosophiques et politiques, t. I, éd. François Matheron (Paris, Stock-IMEC, 1994), at p. 244; see also Jean-Baptiste Vuillerod, La Naissance de l’anti-hégélianisme. Louis Althusser et Michel Foucault, lecteurs de Hegel, Paris, ENS Éditions, 2022, p. 11-13.

[6] Karl Marx, “Postface to the Second Edition,” (1873), pp. 94-103, in Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume One, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), at p. 103.

[7] Marcuse, Reason and Revolution, at p. vii.

[8] Frantz Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1952), at pp. 210-215.

[9] Michel Foucault, “Prison talk,” in Gordon, Colin (ed.) Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–77 (New York: Pantheon, 1980), at p. 53.

[10] Kevin D. Roberts, “Foreword: A Promise to America,” 1-17, in Project 2025 Presidential Transition Project, Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise (Washington D.C.: The Heritage Foundation, 2023), at 4 (emphasis in original).

[11] Roberts, Project 2025, at 3.

[12] Roberts, Project 2025, at 4.

[13] Roberts, Project 2025, at 4.

[14] Roberts, Project 2025, at 4-5.

[15] Roberts, Project 2025, at 11.

[16] Roberts, Project 2025, at 11.

[17] This is not unique to Hegel. It is true as well from the centuries-long confrontations with Descartes, or more recently, with a philosopher like Husserl.

[18] Roberts, Project 2025, at 3.

[19] See https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2025/05/19/vance-pope-leo-love-samaritan-holocaust/

[20] Michel Foucault, The Order of Discourse. Inaugural Lecture at the Collège de France, given 2 December 1970, 51-78, in Untying the Text: A Post-Structuralist Reader, ed. Robert Young (Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1981), at p. 51.

[21] Foucault, The Order of Discourse, at p. 51, quoting Samuel Beckett, “The Unnamable,” in Trilogy (London: Calder and Boyars, 1959), at p. 418.

[22] Michel Foucault, The Order of Discourse. Inaugural Lecture at the Collège de France, given 2 December 1970, 51-78, in Untying the Text: A Post-Structuralist Reader, ed. Robert Young (Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1981), at p. 51.

[23] Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1977), available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1859/critique-pol-economy/preface.htm.

[24] Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, trans. Martin Nicolaus (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), at p. 84.

[25] Marx, Grundrisse, at p. 83.

[26] Marx, Grundrisse, at p. 83.

[27] Marx, Grundrisse, at p. 83.

[28] Karl Marx, Capital. Volume 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Vintage, 1977), at p. 125.

[29] Karl Marx, Capital. Volume 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Vintage, 1977), at p. 125.

[30] Karl Marx, « Preface to the First Edition », Capital. Volume 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Vintage, 1977), at p. 90.

[31] Roman Rosdolsky, The Making of Marx’s Capital (London: Pluto Press, 1992).

[32] Marx, « Preface to the First Edition », Capital. Volume 1, at p. 89.

[33] G.W.F. Hegel, Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, trans. T.M. Knox (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952), ¶ 71, Remark.

[34] G.W.F. Hegel, Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts (Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp Verlag, 1970) (Werke 7), ¶ 249, at p. 393.

[35] Bernard E. Harcourt, “The Systems Fallacy: A Genealogy and Critique of Public Policy and Cost-Benefit Analysis,” Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 47, No. 2, 419-447 (June 2018) https://doi.org/10.1086/698135.