by Bernard E. Harcourt

Abstract

Steve Bannon just called, this month, for a three-state solution in Israel—the third state being the Christian nation of Jerusalem. Bannon calls himself a Christian nationalist. But this raises a puzzling question: How can Christian faith fuel the far Right when it also nourishes the Left (think here for instance of the sanctuary churches movement)? Does Christianity necessarily entail reactionary political views? This essay explores the relationship between the form and political content of theological and philosophical traditions. It focuses on the early works of the French philosopher Louis Althusser, who, in the postwar period, tried to reconcile Christianity with Leftist politics and Hegelian philosophy. It demonstrates how form and content can be linked, but in the end, more than anything, the essay underscores the need for the Left to develop a new comprehensive philosophy to inspire political action today.

Steve Bannon and Christian Nationalism

This month, Steve Bannon called for a three-state solution in Israel, with the third state being a Christian nation in control of Jerusalem. “If you’re going to have a two-state solution, you have to have a three-state solution,” Bannon said on his podcast, and “one of those states has to be the Christian state of Jerusalem.”

Already in 2019 Bannon argued that the only way to guarantee the welfare of Israel, and of American Jews for that matter, was what he called “a hard-weld with Christian nationalism.” The future of American Jews, he said, was “conditional upon [that] one thing.”

Now Bannon is arguing for a Christian state in Israel. “If you really want to protect the Holy Land,” he claims, “the Christians are going to have to get their own stake in this.”

Bannon considers himself a Christian nationalist. He is not alone. Christian nationalism is widespread on the far Right. It buoyed Donald Trump’s third run for president—especially after he survived an assassination attempt in Butler, Pennsylvania, in July 2024, which many on the Right saw as the hand of god. Naturally, Trump played along and encouraged those beliefs, telling a crowd that “Many people have told me that God spared my life for a reason, and that reason was to save our country and to restore America to greatness.” Today, a large number of MAGA supporters view Trump as a messianic figure.

This is part of a broader religiosity on the American Right. Even among less extreme evangelicals, Christianity plays an important role on the far Right. Forty-four percent (44%) of Republicans, for instance, believe that President Trump’s election in 2024 was “part of God’s overall plan.”

Christian faith is deep on the Right. The worldview of the Heritage Foundation, a leading far Right think tank, is grounded on Christian faith. The conception of liberty at the heart of the Heritage vision—and its Project 2025 “Mandate for Leadership”—revolves around Christian beliefs. They conceive of freedom as fulfilling god’s intentions for us as human beings. It is tied to our divine essence as human beings, which consists of matrimonial relations between a man and a woman, procreation, and raising a traditional family. Liberty is understood as a form “blessedness.”[1] Being free is giving full expression to our divine nature: “Our Constitution grants each of us the freedom to do not what we want, but what we ought to do,” Kevin Roberts, the President of the Heritage Foundation, explains.[2]

Even secular Right thinkers are turning to Christian faith. Just this month, Charles Murray published an autobiographical account of his intellectual conversion to Christianity. Murray charts, in his new book Taking Religion Seriously, his own agnostic intellectual struggles with religion and, ultimately, his newfound Christian faith. His is a story, precisely, of the welding of conservatism and Christianity.

Does Christianity Lean Right?

This raises a question: Does Christian belief lean Right? Is Christianity tied to conservatism?

The question has been a source of contentious debate for, well, centuries—and I hesitate to wade into that debate in only a short essay. What is certain is that, historically, Christian faith has nourished Leftist politics as well, from Liberation Theology and sanctuary churches to forms of Christian Marxism. This is true of other religious faiths and traditions. One need only think of the Nation of Islam and the trajectory of Malcolm X.

In the United States today, the evidence indicates that Christian faith among white adults correlates with membership in the Republican Party, whereas Christian faith among black adults correlates with membership in the Democratic Party.

So what is clear, even today, is that Christianity can lead believers into very different political directions.

This, then, raises perhaps a more interesting question: How is it possible that Christian faith could nourish the far Right when the same religious tradition has given birth to Liberation Theology, the sanctuary church movement, and forms of Christian Marxism? What does that say about Christian faith? Is it just empty words that can lead in any political direction whatsoever? Is there any necessity between Christian faith and concrete political outcomes? And if not, should religion just stay out of politics?

How can one reconcile the position of the Heritage Foundation or the Christian nationalism of Steve Bannon with the fact that so many thinkers of Christian faith hold diametrically opposite views—like my brilliant and dear colleague, Thomas Anthony Durkin, who passed away just a few months ago, who was convinced that the early Christian fathers were effectively communists?[3]

To address this question, I propose examining here the writings of a brilliant philosopher who attempted to bridge Christian faith with Left politics, and also self-consciously addressed the question of the necessary link between form and content—between belief systems and political positions, between theory and practice. The French philosopher, Louis Althusser, dedicated his early years to reconciling his Christian faith with his Leftist beliefs and to interrogating the question of the relationship between form and content. So, it makes sense to look more closely into Althusser’s philosophical project.

The Young Louis Althusser

We could begin with Louis Althusser’s first article, titled “The International of Decent Feelings,” written in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, in 1946.[4]

In the article, Althusser proposes a synthesis of Christian faith and Leftist political thought. The synthesis operates by means of the concept of “destiny” or “fate,” which Althusser borrows from the young Hegel, more specifically, from one of Hegel’s earliest writings, his 1799 essay on The Spirit of Christianity and Its Destiny. The title in German is Der Geist des Christentums und sein Schicksal, and the German word “Schicksal” translates as fate, destiny, or even fortune, future, or lot.

So the young Althusser, who is almost 29-years-old at the time, plies the Christian concept of destiny that he takes from the Christian writings of the 29-year-old Hegel to advance a Leftist agenda of revolutionary workers movements.

At the time, Althusser was still more Christian than Marxist, although he was trying to synthesize the two seamlessly. Raised Catholic, and a devout Catholic in his youth (and on the far Right as well), by 1946 Althusser resumes his studies at the École normale supérieure at the rue d’Ulm in Paris (“ENS”) after spending five years in a Stalag, a German prisoner of war camp, in Schleswig, Germany, as a captured French soldier.[5] He is not yet a member of the French Communist Party, which he will join two years later, in November 1948. At the time, he is still a practicing Catholic.[6] And he plunges into the youthful writings of Hegel, that are all on Christian theology and tie Hegel’s religious thought to his political philosophy.

This may be surprising to those who are more familiar with Althusser’s mature writings—and Hegel’s as well. Althusser is best known for the thesis he developed in the mid-1960s which identified what he called an “epistemological break” in the thought of Karl Marx—a discontinuity between the youthful philosophical writings on the one hand and the mature scientific economic writing evidenced in the first volume of Capital on the other. Althusser located the break in 1845 after Marx had dedicated himself to the critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right in his Kreuznach notebooks of 1843 and to the critique of The Phenomenology of Spirit in his Paris manuscripts of 1844, so at the time of the writing of what is commonly referred to as The German Ideology, the Brussels manuscripts in 1845. Althusser argued in his most well-known works, For Marx and Reading Capital in 1965, that the only way to truly understand and operationalize Marx’s thought is to sever and to ignore the philosophical writings of Marx’s youth, all of which engaged Hegel’s thought. One had to, in effect, excise the young-Hegelian philosophical Marx.

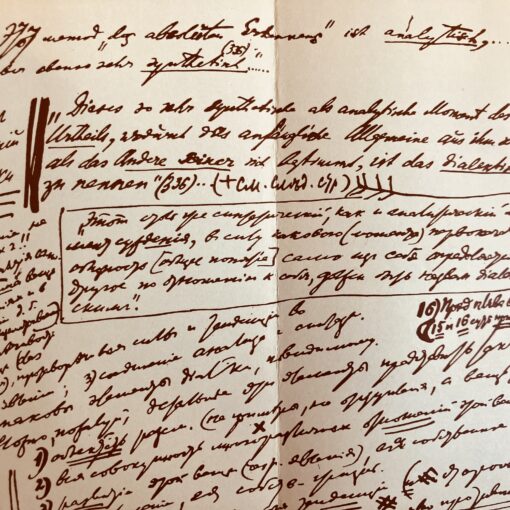

What is less well known is that Althusser started his intellectual journey as a young Hegelian himself, a devout Catholic, who deliberately retained his Christian faith in his Leftist political worldview, by means of lengthy elaborations of Hegel’s writings—both the youthful Hegel writings on Christianity and the mature phenomenological and political writings. In effect, Althusser dedicated himself to reconciling Christianity, Marxism, and Hegelianism. His Master’s thesis was a lengthy treatment of Hegel’s thought, titled “On Content in the Thought of G.W.F. Hegel”—in published form almost 200 pages long.[7] But let’s start with his first unpublished article.

Louis Althusser, “The International of Decent Feelings” (1946)

Althusser’s article a year earlier, in 1946, “The International of Decent Feelings,” is a critique of liberal and existentialist French philosophers, such as André Malraux, Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Arthur Koestler, who, Althusser believed, were mounting a false flag operation against the workers’ movement. It is a fierce critique—in a letter to his parents, he refers to the draft as “quite virulent.”[8] He attacks them for coopting the idea of human fate or destiny towards a centrist or reformist political agenda—what was referred to at the time as “humanism,” but a middle-of-the-road humanism. Althusser does not aim his venom at the far Right or fascists, but at moderate, left-wing, centrist, liberals who are effectively, on his view, undermining the workers movement.

Althusser’s argument, in essence, is that these humanists have created an illusion, namely, that in the immediate post-war moment the fate of humanity as a whole is at risk. They turned the crises of the moment—the atomic bomb, new technologies, the apocalyptic conditions of post-war Europe—into the myth that mankind was facing an existential threat. Mixed with a political pessimism, this myth of generalized human risk, threat, and fear led them to a conciliatory consensus politics, a soft liberalism that operated hand-in-hand with capitalism. As Fred Moten explains, “Althusser denounces the international of decent feelings because it attempts to erase antagonisms that are the necessary precursors of revolutionary theory and practice.”[9]

By contrast to this humanist myth and its accompanying fear of a human destiny that ends in apocalypse, Althusser recuperates a Christian notion of destiny wedded to the emancipation of man. He emphasizes that the atomic bomb itself is nothing more than the product of human labor, and draws a parallel between the mythic fear of that human product (the atomic bomb) and the workers’ condition of being subjugated by the product of their own work.

The path forward, he argues, is to reconcile human beings with their true destiny, by which he means workers coming into control of the means of production. “The road to reconciliation of mankind with their destiny is essentially their appropriation of the products of their labor, of their work in general, and of their history as well,” Althusser writes in 1946. “This reconciliation presupposes the transition from capitalism to socialism through the liberation of the proletariat workers, who not only, through this act, can liberate themselves, but also liberate the whole of humanity from its contradiction and, moreover, from the apocalyptic fear that besieges it.”[10]

At this critical juncture of his argument, Hegel appears, but the young Hegel of The Spirit of Christianity and Its Destiny(1799). Althusser inserts a quick, short reference to the book, writing: “Destiny is the consciousness of self as an enemy, said Hegel.”[11]

Althusser’s point is that Malraux, Camus, and the humanists express fear for their own destiny in the face of the atomic bomb and apocalyptic war—which haunts the horizon like a specter. In the face of this fear of their fate, they can no longer see their own image in mankind. They no longer recognize themselves. And so, Althusser writes, quoting Hegel, they treat their own destiny as an enemy. They “break the silent bonds that united them to their destiny and curse it.”[12]Faced with this mythic threat to the human condition, the reformists protest against a destiny that they feel is escaping them.

But in the face of this “political pessimism,” Althusser posits another conception of destiny that is both Christian and Leftist. He argues that we are not all equally situated. Our supposed equality in the face of threat is an illusion, a myth that must be denounced as such “by Christians.”[13] Althusser writes:

For we believe as Christians in the human condition, in other words, we believe in the equality of all men before God and before His Judgment, but we do not want God’s judgment to be concealed from us, and we do not want non-Christians and sometimes Christians to commit the sacrilege of taking the atomic bomb for the will of God, equality before death for equality before God, […] and the tortures of concentration camps for the Last Judgment.[14]

No, we must reject this pessimistic path, as Christians Althusser says. We must acknowledge that the workers’ condition is far different. And we must seize a truly Christian conception of destiny that will lead to solidarity and cooperation.

Althusser draws the implication, in italics: “We await the advent of the human condition and the end of destiny.”[15] By which he means, the workers movement and the passage to socialism will be the start of the human condition, the end of the humanist myth of destiny, and the realization of humanity’s true destiny. That is Hegel’s message, Althusser suggests.

Hegel himself had turned in his youth to Christianity—in a protestant style—to resolve the tension he felt in the formalism of Kantian morality and certain religious traditions (especially Judaism according to the young Hegel). Hegel’s idea of destiny involved, precisely, a reconciliation of reason and passion, of faith and rationality, of duty and desire. Similarly, Althusser’s idea of destiny reconciles the alienation of mankind from their labor, their work, their oeuvre, their history.[16]

That is where the essay ends. We are missing a few passages or pages, but the last words, it appears, are:

In this struggle, we will fight as well against the myths that seek to rob us of the truth: we are hungry for the truth, and we love it like the bread it tastes like. In this struggle, we do not reject good intentions, but we need the will and comrades who are willing to listen and to see. It is not the deaf and the blind who will guide mankind in the friendship of their destiny.[17]

This is, naturally, a very different view of Christianity and its political implications that we find in Steve Bannon’s Christian nationalism. Far more attractive on my view, even if I do not consider myself a Christian.

But it simply raises again, and does not resolve, the original question: If in fact Christian faith can lead to Bannon’s argument for a Christian nation in Jerusalem and to Althusser’s call for a workers’ revolution and socialism, then are Christian teachings void of any content? Is there a complete divorce of the formal aspects of Christianity—the logics, language, epistles, teachings—and the political substance or content that can be derived from it? Is there, in fact, an alienation of form and substance in Christian faith, one that Hegel protested against in his youth and tried to resolve in The Spirit of Christianity and Its Destiny?

Louis Althusser, “On Content in the Thought of G.W.F. Hegal” (1947)

Perhaps Althusser was driven to this very puzzle by the end of his own article. In any event, Althusser turns to this precise question in his first major work (also unpublished during his lifetime), his Diplôme d’études supérieures at the Sorbonne, what was in effect his Master’s thesis, which he defended in 1947 under the supervision of the French philosopher of science, Gaston Bachelard. And although Althusser plunges deeply, in the first part of his thesis, into the youthful writings of Hegel on Christianity, Althusser poses the question to the entire Hegelian corpus, rather than simply to Christianity.

The central question that Althusser poses is whether the political outcome of Hegel’s writings are the necessary product of the form or logic of his philosophy, or if there is instead a disjuncture, an alienation of form and substance. And if the latter, whether there is any value to Hegel’s thought. In other words: Are form and substance, are theory and practice, related? Because if not, we can simply dispense with the form, the logic, the theory, the philosophy, or the religion, and simply fight over the politics.

The question Althusser poses in his thesis is the following: How is it possible that the same Hegelian dialectic, the same intellectual form, the same language, the same logic, could have given rise, ten years after Hegel’s death, to both a right-wing Hegelianism and to its opposite, the young or Left Hegelians, including Marx and Engels? Or, turning to his present, 1947, how is it possible that Hegelian thought could nourish humanist existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre, moderate or reformist humanists such as André Malraux and Jean Hyppolite, dogmatic or deterministic Marxists, and a range of phenomenologists? How could such disparate thinkers all feed at the trough of Hegelianism?

The same question, of course could be asked of Christianity. Should we therefore free ourselves from the form of thought or from its political content?

To bring us back to our crises and problematics of today—for we face the same dilemma—we could similarly ask ourselves: How is it possible in the United States that the same religious faith (most often Christianity, but it is true of others) can serve as a basis for conservative or reactionary or even counter-revolutionary far Right politics, but also for progressive movements? How could it nourish both the Heritage Foundation and the sanctuary church movement?

Althusser tackles this exact question by interrogating the “content” of Hegel’s thought. That is the very title of his Master’s thesis, “Content in the Thought of G.W.F. Hegel.”

What does “content” mean? For Althusser, the concept of content is opposed to that of form—by which he means the Hegelian dialectic, the logical form of the dialectic, dialectical reasoning. So the question Althusser asks in his thesis is whether it is possible to separate form and content in Hegel’s thought.

The question arises because, almost immediately after his death, there arose both right-wing and left-wing versions of Hegelianism. We are all familiar with the Young Hegelians who were left-wing thinkers and, in a way, survived history: Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, Max Stirner, and of course, the young Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who would later break away from them and become more radical. We hardly read the right-wing Hegelians today and hardly remember their names. But some of them include Heinrich Leo, Leopold von Henning, Johann Philipp Gabler, Hermann Hinrichs, Karl Daub—thinkers few of you have probably heard of.

“The lesson of history is unequivocal,” Althusser writes: “Hegel himself became the decomposition of Hegel. Ten years after the Master’s death, his work fell apart, divided, developed in opposing directions, became the site of a struggle, and was itself a struggle: ‘Ich bin der Kampf’ [I am the struggle].”[18]

Hegel’s thought immediately became alienated, fractured, split in two, in two diametrically opposed political directions. A great paradox: a philosophy that synthesized, a philosophy that led to an absolute summit, a philosophy that prided itself in reconciliation, unification, unity, overcoming of contradictions, a system that led us to the summit of knowledge, of self-consciousness, of our awareness of ourselves as containing all previous philosophical and material stages—very much like Christianity (which explains why Hegel’s absolute spirit is often interpretated in a religious way)—suddenly finds itself, right after Hegel’s death, pulled in opposite political directions. This is quite remarkable.

Althusser asks himself: How is it possible that the same work, the same logic, the same dialectic would give birth to two opposite political “contents”?

Another way of asking the question: Is there a direction or a necessity to the Hegelian dialectic? Or is the form of the dialectic indeterminate? Can it lead us in any political direction, or is there a connection between the content and form of dialectical reasoning in Hegel’s thought?

These are, as I am sure you realize, questions that critical thinkers have asked themselves throughout the ages about the form of criticism itself—whether in critical theory or in Christianity. It is, for instance, at the heart of Duncan Kennedy’s landmark article “Form and Substance in Private Law Adjudication,” which contributed to the birth of Critical Legal Studies in the 1970s. These are long-standing issues for thinkers of all stripes, since it affects so many different fields.

Althusser formulates the questions precisely: “Whether dialectics is a form imposed from outside or whether it is the development of content, whether it is formal or real, whether the schema is a purely mechanical process or the soul of things.”[19]

Althusser’s Response, in Three Parts

Now, to answer these questions, Althusser turns to an immanent examination of Hegel’s thought. He burrows inside it. He seeks the answer in Hegel’s thought, not outside it—somewhat like the Critical Theory approach of the Frankfurt School: to enter, or in his words, “to penetrate inside the truth.”[20] As he writes, “Perhaps then it will be possible to determine whether Hegelianism is indeed a philosophy of the content, or a superficial formalism, and to resolve the paradox of the most rigorous of systems justifying the least rigorous of institutions, and ultimately breaking down as if its very rigor were borrowed.”[21]

Althusser tackles the question in a first part entitled “Birth of the Concept,” by returning to the young Hegel, particularly The Spirit of Christianity and Its Destiny (1799), to demonstrate that this problematic of formalism versus content is something that Hegel himself had directly confronted in his youth.

For Hegel, the problem stemmed from a feeling of emptiness in the face of Enlightenment philosophy and its emphasis on reason. Hegel shared this feeling with other German Romantics, such as Friedrich Schiller—a sense that obligation and reason alone do not move us as human beings, that something more is needed, like will, spirit, passion. As Althusser writes, “In this world emptied of its truth, the young Hegel and his friends from Tübingen, Hölderlin and Schelling, aspired to a regained fullness.”[22] Here too, one can sense an element of alienation—between beliefs and duties, between thought and action, between knowing and doing—one that Hegel associates with Immanuel Kant. As Althusser writes, Kant is the philosopher, for Hegel, who wants to “learn to swim in order to jump into the water.”[23] The problem with Kantian morality is that we are forced to act because of the categorical imperative, instead of acting according to our desires and ethics. What Althusser is reaching for, with Hegel, is a reconciliation of these forms of alienation, of separation, in effect a unity of form and substance.

In a second part titled “Knowledge of the Concept,” Althusser tackles Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit and Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, the more mature writings. Althusser performs a dialectical analysis of the concept of content, in effect a three-step movement where the third moment, the most important, becomes the self-consciousness of the content in history. The discussion is abstract, but taking the example of a specific content, citizenship for example, can offer a more concrete understanding. So let’s take the example of citizens who recognize each other as equals and not as master and slaves. According to Althusser, Hegel argues that the concept of citizenship cannot simply be understood if it is taken as a given, if it is taken for granted, nor through mere reflection. Instead, it must develop through history, through the experience of the French Revolution, through the actualization of the content in history and through historical experience.[24] This should remind you of the end of the Phenomenology of Spirit, which leaves the reader, in the aftermath of the French Revolution and the Terror, in a rational and fulfilled world of equal citizenship.

But this is where things become problematic for Althusser, because that is not the world that Hegel describes and defends in his work Principles of the Philosophy of Law, what we generally call The Philosophy of Right, fourteen years later in 1820. Instead of equal citizenship in the wake of the French Revolution, the “content” becomes that of a hereditary constitutional monarchy, which represents a hierarchy, a pyramidal structure, the very opposite of Hegel’s dialectical circle. It leads to an authoritarian Prussian bureaucracy, where there is no place for equality, but rather inequality and hierarchy, where there is no room for freedom, but rather, as Althusser writes, “the bulkheads of corporations, bureaus, and police forces.”[25] Here, Althusser pens one of the best lines of his thesis: “The reason of the State is nothing more than reason of state, a reason of another world hiding the unreason of this world.”[26] As well as this other great line: “The individual does not find his fulfillment and liberation in the State, but rather the official recognition of his servitude and alienation.”[27] That sense of alienation also attaches on the side of the monarch, who is himself split in two—with, on the one hand, his individuality as a human being, and on the other, the crown—reminding us of Kantorowicz’s brilliant work on the King’s two bodies.

Inversions and cyclical turnings

It is at this point, in the third part titled “Misunderstanding of the Concept,” that Althusser initiates a series of operations on Hegel’s thought that can be described as inversions or cyclical turnings.

1. An epistemological break in Hegel

First, Althusser draws on Marx’s 1843 manuscripts, Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, to identify a distortion in Hegel’s political analysis, and on that basis, Althusser effectuates an epistemological break avant-la-lettrewithin Hegel’s writings.

In 1843, Marx had critiqued Hegel for not following through on the implications of his philosophy for politics. As noted, instead of leading toward equal citizenship in a democratic setting, Hegel promoted a hierarchical political system of constitutional monarchy in his Philosophy of Right in 1820. Marx’s critique serves the role, for Althusser, of identifying Hegel’s misstep, or the perversion of the political content.[28] Remarkably, Althusser uses the terms “error” and “falsity”[29]—harsh terms for a young philosopher. Marx’s critique of The Philosophy of Right demonstrates that Hegel left the reader in a form of alienation between on the one hand the private selfish interests of the middle class in society and on the other hand the universal interests of the State. Marx argued instead for resolution through “true democracy,” where he believed Hegel had ended in his earlier work written in Jena in 1806 as Napoleon took control of the city.

Althusser diagnoses the problem as the product of an unfortunate epistemological or political break in the writings of Hegel. I said avant-la-lettre earlier, because Althusser has not yet developed his most famous argument, which he would in the mid-1960s, about the “epistemological break” in Marx around 1845, at the time of the writing of The German Ideology, that would lead Althusser to sever and abandon the young Marx. Here, Althusser does not mention the notion of an epistemological break—but the idea is subliminally present in the text: Althusser draws a line between the early Hegel of the Phenomenology of Spirit in 1806 and the Hegel of The Philosophy of Right in 1820. He effectively urges us to abandon the later Hegel. He tries to sever the conservative political thought of The Philosophy of Right and leave us only with the revolutionary historical development from The Phenomenology of Spirit. The break is reflected—clearly, in my view—when he refers to the later work as “the unfortunate texts of the Philosophy of Right and the Philosophy of History”—in his words, “les malheureux textes.”[30]

2. Return to the dialectic

For Althusser, however, the problem he and Marx identify in Hegel represents just a moment in the Hegelian dialectic. It is therefore necessary, as a moment in the dialectic, and can be overcome by continuing the dialectical reasoning. The problem is that Hegel remained, in 1820, at too abstract a level. That abstraction is precisely what the Hegelian dialectic overcomes. And so in effect, the form of alienation that remains in The Philosophy of Right (between the egoistical interests of the middle class and the universal interests of the State) can simply be resolved by prolonging Hegel’s work—the work of the dialectic, the process that Hegel described in his works on Logic (both his book The Science of Logic from 1812-1816 and the Logic from Part 1 of the Encyclopedia in 1817). In effect, Hegel’s political content in 1820 was distorted, but the error represented an essential contradiction, and it can be overcome using the logical process that Hegel calls his dialectics.

Interestingly, Althusser argues here—and this is the second reversal—that Marx was too dismissive of Hegel and did not recognize that Hegel’s own internal logic provided the way forward. In fact, Althusser suggests, Hegel realized an essential point that Marx himself overlooked or ignored—in French, “que Marx néglige.”[31] Marx serves as a corrective, but he must then be augmented by Hegel’s own logic and Hegel’s work on the concept (which Hegel elaborates in his two Logics).[32] Or, to be more precise, Hegelian logic and method are needed to complement Marx’s critique of Hegel’s political thought, which corrects it and puts us on the right path, but which requires a return to Hegelian thought to accomplish that with necessity.

You will recall that Marx had pointedly remarked, in his critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, that Hegel’s true interest in that work was not politics, but logic—that the political work was just the unrolling of his Logic. Marx famously wrote that “It is not the philosophy of law, but rather the logic that constitutes the true center of interest [in The Philosophy of Right]. […] What is philosophical in all this is not the logic of the matter, but the matter of Logic. It is not the Logic that serves to demonstrate the State, it is the State that serves to demonstrate the Logic.”[33]

In effect, Marx argued that Hegel got lost in abstractions, that he got distracted trying to realize the actual. But at that point, Althusser argues, Hegel’s own logic becomes crucial for continuing Marx’s and Hegel’s work. Hegel stopped at the level of abstraction. But as Althusser writes, “abstraction is only the locus of Hegelian alienation.”[34] Hegel can get lead us out of the abstractions, and this reflects, in Althusser’s words in 1947—which may surprise readers who are more familiar with the later Althusser—“the greatness of Hegel.”[35]

3. Ending with Marx

In a third and final moment, at the end of his thesis, Althusser returns to Marx to give texture to Hegel’s political content, which we know in the Phenomenology of Spirit ended in a revolutionary manner.

Hegel provides the logical path forward. As Althusser writes, “We owe this conception of history, as fundamental element and meaningful totality, to Hegel. We also owe Hegel the ability to identify the rational nature of this totality with the nature of human totality”[36]

But to truly understand where it all leaves us, at the final revolutionary moment of the dialectic, we need to turn to Marx and his interpretation in Capital of the economic bases of this human totality.

Ultimately, the final resolution of Hegel’s political thought is achieved in the revolutionary action of the workers movement. Althusser writes, “Revolutionary action can conceive, at least formally, the advent of human totality reconciled with its own structure.”[37] And he concludes with these words: “The future lies, for us, in the secret movements of the present content; we remain in a totality that is still obscure totality and that we must bring to light.”[38](217)

Althusser does not view these three different moments as “inversions” of Hegel. He rejects Marx’s well-known idea of putting Hegel back on his feet. He suggests that the idea of turning Hegel on his head—made famous by Marx—makes little sense because Hegels’ thought is circular, rather than vertical, and that one cannot turn a circle on its head. Althusser asks “what could a circularity put back on its feet amount to?”[39]

The idea of inversion or reversal is not the right way to think about the relationship between these thinkers, Althusser suggests. Marx did not simply turn Hegel on his head and transform idealism into materialism. Rather, the circular logic of dialectical movement must continue. And that is precisely what Althusser proposes: the continuation of the logic of historical transformation that leads beyond the revolutionary form at the end of the Phenomenology of Spirit toward a new revolutionary movement led by workers.

The Stakes of the Matter

At the end of the work, Althusser returns to the political stakes of the matter. He explains the seriousness of the problem, what he calls the “fundamental problem of our time.”[40]

The fundamental problem is that practically all the different philosophical and political positions in his contemporary moment constitute mere fragments or crumbs of Hegelian philosophy—we might here think of our original analogy to Christian beliefs. All of the political factions simply take up pieces, portions, or splinters and not the totality of Hegelian thought. Modern existentialists, such as Jean-Paul Sartre, appropriate the subjective elements, the subjectivity, the will of the individual. Determinist Marxists, on the other hand, appropriate the objective elements, the structure. Contemporary phenomenologists of different stripes return to the experiential elements. As Althusser writes, “Contemporary thought was formed in the decay of Hegel, and feeds off it. Ideologically speaking, we are thus under the domination of Hegel…”[41]

Those political factions are thus stuck in a scattering of Hegel. The way forward, Althusser argues, is to unfold Hegel’s dialectical reasoning properly and actualize it in the real world of the workers’ movements and revolutionary actions—to reconcile theory and practice.

Another Turn: Althusser, “The Return to Hegel” (1950)

Three years later, in 1950, Althusser would begin his own break from Hegel. In an article titled “The Return to Hegel: Last Word of Academic Revisionism”—and this one, by contrast to the earlier two, published, in La Nouvelle Critique—Althusser makes a violent break from Hegel, from his university peers, and from the entire tradition of mainstream French philosophy.

The article takes aim at the French establishment of university philosophy professors who have turned to Hegel’s philosophy—especially the philosopher Jean Hyppolite, who had reintroduced Hegel’s work to the French academy with his French translation starting in 1939 of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit and his publication in 1948 of a treatise on the text titled Genesis and Structure of the Phenomenology of Spirit of Hegel.

The puzzle that motivates Althusser is why French philosophy, which had been so very hostile to Hegel throughout the nineteenth century, suddenly adopted him in about 1932 at the dawn of the twentieth century. “How can we understand this reversal?”, he asks.[42]

Althusser’s answer: for the same reasons that Hegel was adopted by the Prussian elite in the nineteenth century. Hegel served Prussian feudalism in its effort to repress and crush the merchant class that was rising up in nineteenth century in Germany. In the same way, Hegel’s writings, particularly on the State, serve the elites in 1950 to crush and repress the rising working class. It is the same gamble, the same ambition, as he says, “to place in servitude the rising class.”[43]Althusser targets thinkers like Raymond Aron, Hyppolite, and their cohorts, accusing them of acting like Mussolini and other fascists across Europe who used Hegelian thought to repress the working class.

The article is brutal, violent. Althusser is talking about fascism and Prussian authoritarianism, and equates French philosophers with them. He is attacking what he calls a “fascist” “operation.” In his words: “This Great Return to Hegel is nothing more than a desperate recourse against Marx, in the specific form that revisionism takes in the final crisis of imperialism: a revisionism of a fascist character.”[44] (256)

Althusser is essentially suggesting that the whole operation of recuperating Hegel is aimed at violence and war against the working classes. It reflects a shift towards a conflictual vision of society, based heavily on Hegel’s dialectic of the confrontation between lord and bondsman—or what is referred to in French at the time as the “master-slave dialectic”—which is at the heart of French philosophy at the time, especially the book of Alexandre Kojève, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, published in 1948 based on lectures delivered in the 1930s.[45]

In this 1950 article, Althusser proposes a brilliant historical account of the trajectory of French philosophy from the eighteenth century to the post-war period—one that I will have to come back to in another essay. There is too much to say.

But what is clear from this fierce article in 1950, as well as from the equally “virulent” (in his words) essay from 1946, is that this will not be the final stage of Althusser’s reflections on Hegel. No, in fact, we are faced here with the inevitability of Hegel’s central place in Althusser’s thinking throughout his entire life. Hegel will be his constant foil. This will lead, in the mid-1960s, in For Marx, to the epistemological break, which attempted to eliminate entirely any possible reference to Hegel in the interpretation of Marx, accompanied by a severe critique of Hegel, followed in the late 1960s and during the 1970s by several texts of fundamental importance on Hegel, Marx, and Lenin, that function as an autocritique of some of his positions from the mid-1960s.

The Young Althusser’s Answer

Althusser thus managed to reconcile the Christian writings of the young Hegel with Hegel’s mature writings in the Phenomenology and two Logics, as well as with Marx’s early critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right and, ultimately, with Marx’s economic writings from the first volume of Capital. Althusser wove together, seamlessly, Christianity, the Hegelian dialectic, and Marxism. In the process, Althusser provided an argument for a necessary relationship between form and content—for a link that inextricably ties together the dialectical logic with the resulting political substance, the politics. Althusser unified theory and practice.

Now, to be sure, one can critique Althusser’s work, try to find gaps in the reasoning, pull it apart—as one can any philosophical or theological work. This is true of all great works in philosophy and religion. One can find contradictions in even the most rationalist of thinkers, like Kant or Descartes.

What matters here, though, is that in answer to the original question—namely, how is it possible that Christian belief or Hegelian philosophy could spawn both right-wing and left-wing politics—Althusser does not back down. He does not concede that form could be disconnected from content. He does not retreat to a purely political argumentation. No, on the contrary, he dedicates himself to proving that the logic, the language, the formality of philosophy necessarily implicates a unique political outcome.

Throughout his life, Althusser dedicated himself to the arduous intellectual task of providing a deep philosophical foundation to Marx. That was his life ambition: to develop the theoretical groundwork for Marxism. And that explains why he had such an influence on the Left during the second half of the twentieth century.

Where does this leave us today?

A New Philosophy for the Left

Today, it feels as if only the far Right has a coherent vision, a philosophy, and clear policy objectives. One may not like them. One may believe they are filled with paradoxes and hypocrisies. But the far Right has a coherent worldview. For the Heritage Foundation, it is based on Christian belief. For Steve Bannon, on Christian Nationalism. For Christopher Rufo, on an explicit “counterrevolutionary” perspective. But these are all comprehensive worldviews. And one of the reasons that the far Right is ascendant today is precisely because they have a comprehensive philosophy. That is the wind in their sails. It empowers people to rally behind them.

The Left had coherent and articulable worldviews in earlier times. FDR heralded a New Deal in the United States, hand-in-hand with a robust philosophy about the need for a “second Bill of Rights” focused on economic and social rights. Building on that, Lyndon B. Johnson gave Americans the idea of the Great Society—a society that would provide for greater economic equality, less racial discrimination, and improved education. Johnson launched the War on Poverty, a whole set of public policy programs intended to reduce poverty for all Americans across the country. Fannie Lou Hamer, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, Thurgood Marshall, Bayard Rustin and so many others fueled a civil rights movement for racial equality built on a philosophy of non-violent civil disobedience—not that different from Gandhi. All of these movements offered Americans a vision of a more just society. They inspired people to act.

In Europe, one particular coherent philosophy, Marxism, played a much larger role and fueled mass movements and parties throughout the twentieth century. In France, for instance, the French Communist Party consistently won over 20% of the first-round elections in the National Assembly from the post-war period until around 1978.

Today, though, it feels as if the American Left has run out of ideas and has no coherent philosophy. Or it has ideas and policies, but not a coherent framework to put them in.

Bernie Sanders presents as a democratic socialist, as does AOC; but they do not espouse or spend much time developing the philosophical bases of their worldviews. They are more policy oriented and issue driven, than philosophical.

Zohran Mamdani has a host of innovative public policies centered around the goal of making New York City more affordable. He is proposing to cap rent increases for rent-stabilized apartments, as Bill de Blasio had done; free public transportation on buses; a city-run city-owned wholesale food grocery store in each borough; more affordable housing, with up to 200,000 new units over the next decade; barring ICE from city facilities; baby baskets of goods to new parents and free childcare; community responders to mental health crisis 911 calls and violence interrupters. These are a remarkable set of policies, and Mamdani’s policy orientation is strategically wise in our political climate.

The central organizing principle of Mamdani’s worldview is making New York City affordable and less of a struggle for its residents. That’s a good message—and far more coherent than the other candidates, whether its Andrew Cuomo, Curtis Sliwa, or the earlier crew, including Eric Adams, who nobody could associate with a single policy or strategy.

But these are not comprehensive philosophical worldviews—by contrast to the far Right. And I fear that this is handicapping the Left right now.

One of the most urgent lessons I draw from all this—including Louis Althusser’s life ambition to provide a philosophical grounding to the Left—is that we need to develop a new comprehensive philosophy of solidarity and cooperation for the Left.

Fred Moten notes that “Althusser appeals to a kind of Christian truth to which I cannot appeal; nevertheless, a discourse of truth is available to us—the simple, banal, inexhaustible record of what “we” do and of “our” motives for doing it.”[46]

I’m afraid that I too cannot appeal to Christian truth, and I hesitate as well to avail myself of Moten’s “discourse of truth,” which in my opinion President Trump has appropriated, exploited, and broken.

It is time now to invent a new philosophical path forward—ambitiously.

Notes

[1] Kevin D. Roberts, “Foreword: A Promise to America,” 1-17, in Project 2025 Presidential Transition Project, Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise (Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation, 2023), p. 3, 13, and 14.

[2] Roberts, Project 2025, p. 13.

[3] Tom Durkin was working on a terrific paper on that when he passed away, and although unfinished, I will see if it is possible to bring it to light.

[4] Louis Althusser, « L’internationale des bons sentiments (1946) », p. 35-49, dans Écrits philosophiques et politiques, t. I, éd. par François Matheron, Paris, Stock-IMEC, 1994; Louis Althusser, “The International of Decent Feelings,” in The Spectre of Hegel, trans. G. M. Goshgarian (New York: Verso, 1997).

[5] See, generally, Yann Moulier Boutang, Louis Althusser. Une biographie, Tome I, La Formation du mythe (1918-1956), Paris, Grasset, 1992, pp. 229-233.

[6] Boutang, Louis Althusser, p. 235

[7] Louis Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 59-238, dans Écrits philosophiques et politiques, t. I, éd. par François Matheron, Paris, Stock-IMEC, 1994; translated in The Spectre of Hegel, trans. G. M. Goshgarian (New York: Verso, 1997).

[8] Althusser, Écrits philosophiques et politiques, t. I, éd. par François Matheron, Paris, Stock-IMEC, 1994, p. 27.

[9] Fred Moten, “The New International of Decent Feelings,” Social Text, 72 (Volume 20, Number 3), Fall 2002, pp. 189-199, at p. 191.

[10] Althusser, « L’internationale des bons sentiments (1946) », p. 49 (my translations here and below)

[11] Althusser, « L’internationale des bons sentiments (1946) », p. 49.

[12] Althusser, « L’internationale des bons sentiments (1946) », p. 35.

[13] Althusser, « L’internationale des bons sentiments (1946) », p. 43.

[14] Althusser, « L’internationale des bons sentiments (1946) », p. 43.

[15] Althusser, « L’internationale des bons sentiments (1946) », p. 49.

[16] Althusser, « L’internationale des bons sentiments (1946) », p. 49.

[17] Althusser, « L’internationale des bons sentiments (1946) », p. 49.

[18] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 62 (my translations here and below).

[19] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 63.

[20] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 64.

[21] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 65.

[22] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 72.

[23] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 83.

[24] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 142.

[25] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 167.

[26] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 177.

[27] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 171.

[28] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 166, 175.

[29] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 166, 175.

[30] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 203.

[31] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 185.

[32] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 187.

[33] Karl Marx, Contribution à la critique de la philosophie du droit de Hegel, trad. Victor Béguin, Alix Bouffard, Paul Guerpillon, et Florian Nicodème (Paris : Les Éditions sociales (LDES), 2018) (édition La Geme), at ¶ 270, p. 94 (my translation)

[34] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 183.

[35] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 185.

[36] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 214.

[37] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 217.

[38] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 217.

[39] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 211.

[40] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 211.

[41] Althusser, « Du contenu dans la pensée de G.W.F. Hegel (1947) », p. 210.

[42] Louis Althusser, « Le retour à Hegel. Dernier mot du révisionnisme universitaire » [1950], p. 243-260, dans Écrits philosophiques et politiques, t. I, éd. par François Matheron, Paris, Stock-IMEC, 1994, at p. 245; Louis Althusser, “The Return to Hegel,” in The Spectre of Hegel: Early Writings, trans. G. M. Goshgarian, ed. François Matheron (New York: Verso, 2014 [1950]).

[43] Althusser, « Le retour à Hegel », at p. 253.

[44] Althusser, « Le retour à Hegel », at p. 256.

[45] Althusser, « Le retour à Hegel », at p. 252.

[46] Moten, “The New International of Decent Feelings,” at p. 194.