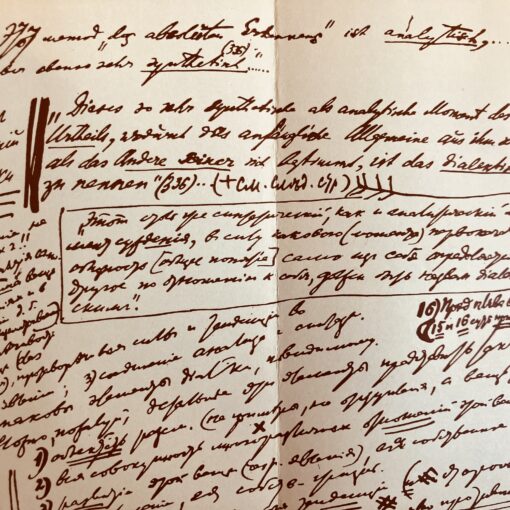

In his darkest moment, at the outbreak of World War I and the outburst of nationalism among Western European workers parties, Lenin plunged into deep study of G.W.F. Hegel’s Science of Logic and the Encyclopedia Logic. In the wells of the Bern library, in exile in Switzerland, Lenin took copious notes and wrote comments on Hegel’s work that fill up his Philosophical Notebooks of 1914-15. As Kevin Anderson has shown, this time of study would shape his political vision, writings, and praxis in 1917, especially on the state, revolution, and imperialism.

Lenin was not alone in returning to Hegel at a deep moment of crisis. C.L.R. James similarly burrowed into Hegel’s Logic in 1948 at a time of disenchantment with the U.S. workers movement, forming a separate tendency within the Left, alongside Raya Dunayevskaya and Grace Lee Boggs, to rethink the foundations of solidarity.

Remarkably, since the nineteenth century and to the present, many of the greatest thinkers of political praxis developed their philosophical positions and political practices in a dialectical confrontation with the systematic thought of Hegel. At practically every stage of Marx’s writings, for instance, he found inspiration in a different dimension of Hegel’s work. In the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, Marx returned to Hegels’ Phenomenology of Spirit. In the Grundrisse, he drew on Hegel’s Science of Logic. And of course, Marx’s 1843 manuscripts were dedicated to a critique of the Philosophy of Right. Following Alexandre Kojève’s famous lectures on Hegel’s Phenomenology, Jean-Paul Sartre would draw extensively on the master-servant dialectic to develop his own brand of existential philosophy, reconcile it with his later politics, and motivate his activism on the war in Algeria and popular uprisings. Frantz Fanon confronted Hegel’s master-slave dialectic directly in his book Black Skin, White Masks in 1952. Herbert Marcuse began his intellectual journey with Hegel in Reason and Revolution, and even before that in Hegel’s Ontology and the Theory of Historicity in 1932. Foucault wrote his master’s thesis on Hegel’s concept of experience in order to develop a materialist theory of experience. Judith Butler wrote her dissertation on the genesis of the desiring subject by tracing it back to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit and its influence on Kojève, Hyppolite, Sartre, Lacan, Deleuze, and Foucault.

Drawing on this long history, the 2025-2026 public seminar “Inversions of Hegel 13/13” explores the myriad ways in which critical thinkers, from the nineteenth century to the present, have confronted Hegel’s thought and in the process invented new radical visions and programs of solidarity, cooperation, and emancipation. This is an urgent task today as we face a growing far-right movement in global politics, figure out new ways to counter the increasingly systematized theories of the extreme Right, and propose new horizons for the future.

Hegel 13/13 is a multi-year project that explores the historical confrontations with G.W.F. Hegel’s thought, from the nineteenth century to the present, with the aim of developing new critical perspectives and practices for today’s times. The ambition of this multi-year project is to serve as a catalyst to produce new forms of critique and praxis to address the present political conjuncture.

This is not a “return to Hegel,” in the sense in which Althusser presciently critiqued post-war French philosophy for siding with Hegel against Marx. That essay by Althusser from 1950 is brilliant and can serve as our starting point. Our project is to see how Hegel has been used and abused in order for us to develop our own critical praxis. These times of crisis call for nothing less.

From early on with Ludwig Feuerbach and the Young Hegelians, to Alexandre Kojève in the 1930s and his influence on post-war French philosophy but also on Allan Bloom, Francis Fukuyama, and American conservative thought, or to the Johnson-Forest Tendency within the U.S. workers’ movement, the contradictions in Hegel’s thought have given birth to some of the most important and impactful political ideas and practices.

It is time then, once again, to return to Hegel, not to think with him, but rather, as it has so often been more productive, to think against and beyond him. It is time for another round of agonistic confrontations with Hegel’s writings—The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), The Science of Logic (1812-1816), the Encyclopedia (1817), and the Principles of the Philosophy of Law (1820).

The multi-year project “Inversions of Hegel 13/13” will begin during the academic year 2025-2026 with preparatory sessions (informal conversations, small seminars, reading groups, and lectures) that will lay the groundwork for a 13/13 public seminar series on the confrontations with Hegel’s writings that have shaped world history. Throughout, the ambition will be to develop a new critical praxis for today.

Bernard E. Harcourt

New York, NY

September 4, 2025