By Bernard E. Harcourt

In this session, we skip forward to the late or the final Marx and welcome Kohei Saito from the University of Tokyo to discuss his own manifesto on degrowth communism titled Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto.[1]

In terms of our year-long seminar, we are effectively jumping over what would constitute the next historical episode: the creation of the International Workingmen’s Association (1864–1876, generally referred to as the “First International” or the “IWA”), the rise and fall of the Paris Commune (March-May 1871), Marx’s addresses to the IWA on the situation in Paris, and his famous essay The Civil War in France read to the General Council of the IWA just a few days after the collapse of the Paris Commune. We will turn to this penultimate historical episode at our next session, Marx 12/13, with Bruno Bosteels, on April 23, 2025.

But for today, we put that penultimate period aside and focus on the late Marx with Kohei Saito. (We will return to the late Marx as well in our closing session of Marx 13/13 with Étienne Balibar on May 27, 2025, in Paris.)

The late Marx is of particular importance to a scholar like Kohei Saito because it is during his final years that Marx expands his repertoire to engage a wide range of areas outside of the classic corpus of political economy he had focused on from the 1840s to the 1860s. In his final years, Marx explores scholarship in chemistry and the natural sciences on the effects of advanced agricultural technologies and practices on the ecosystem. He reads works on the history of political development in India, Russia, and Algeria. Marx consults the work of anthropologists on pre-capitalist societies. He explores work on land use and actual practices in ancient Rome, in South America, and among the indigenous peoples in America.[2] He reads the anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan and takes copious notes in what has come to be known as his Ethnological Notebooks. He annotates the work of the natural scientist Justus von Liebig in the field of agricultural chemistry, Organic Chemistry in its Application to Agriculture and Physiology (1840), and the agriculturalist Karl Fraas’ Climate and Plantlife throughout the Ages (Klima und Pflanzenwelt in der Zeit, 1847). He reads the work of the German legal historian Georg Ludwig von Maurer on the history of the early village institutions among the Germanic peoples and the question of communal property. He explores the climate and agriculture of Egypt, Greece, and Mesopotamia. He reads the studies of William Stanley Jevons warning of the shrinking deposits of easily accessible coal in England. All his copious notes are now being collected in the MEGA2 edition of his complete works.

During the period, Marx publishes far less than he had in earlier decades. His manuscript notebooks fill volumes of the new MEGA2 edition of his and Engels’ collected works, but practically none of it had been published. The most important writings from these final years, especially for scholars of the late Marx, include the following, listed in order of importance rather than chronology:

- The drafts and final letter that Marx wrote to the Russian revolutionary Vera Zasulich in February and March 1881.

- The preface to the second Russian edition of The Communist Manifesto that Marx and Engels published in 1882.

- The Critique of the Gotha Program that Marx published in 1875.

- The Ethnological Notebooks that he kept during his readings and study.

These texts form the backbone of the late Marx that Kohei Saito analyzes in his work Slow Down and in his earlier books, including Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism: Capital, Nature, and the Unfinished Critique of Political Economy, published in 2017.

In this, Saito is not alone, but forms part of a burgeoning research cluster of Marx scholars who have unearthed a “Late Marx” or the “Last Marx.” The effort traces back at least to the 1970s with the work of scholars such as Wada Haruki in Japan, the author of Marx, Engels and Revolutionary Russia in 1975, Maurice Godelier’s edition of Marx and Engels’ texts on precapitalist societies published in 1973, and the publication in 1972 of Marx’s Ethnological Notebooks.[3] Today, scholars working on the late Marx include Marcello Musto, author of the 2016 book, The Last Years of Karl Marx: An Intellectual Biography; Teodor Shanin and the contributors to Late Marx and the Russian Road: Marx and the Peripheries of Capitalism; Bruno Bosteels in his book La Comuna Mexicana; Kolja Lindner and the scholars surrounding the publication of the collected edition of Le Dernier Marx (Asymétrie, 2019); Michael Löwy, Pier Paolo Poggio, and Maximilien Rubel, authors of Le dernier Marx, communisme en devenir (2018); and others.[4]

What is unique about Kohei Saito’s work, though, is that he marries the late Marx with an argument for degrowth communism. While others have wedded the late Marx to ecological aspirations and ecosocialism, Saito goes further and argues for degrowth.

Saito’s advocacy of degrowth communism includes, at its heart, an argument for worker cooperatives, consumer coops, and mutual aid. It embraces the ambition of an economic regime of mutually reinforcing cooperative enterprises, or what I call Coöperism. In fact, that is how he starts the English edition of his book, Slow Down.

Saito opens the preface to the English edition with an anecdote about a time that he was presenting a public lecture in Suzuka City, the home of Honda’s principal car factory and of the Suzuka Circuit, the Japanese equivalent of the United States Grand Prix. After his talk, he was approached by a man who had come all the way from Tokyo, a three-hour ride, who told him about his dilemma and asked for advice. The man owned a rubber plant and had come to realize the ecological damage that the plant was doing. Saito responded to the man that he should convert his company into a worker cooperative. Saito writes:

My answer was that he should sign his business over to its employees. Since capitalism is the ultimate cause of climate breakdown, it is necessary to transition to a steady-state economy. All companies therefore need to become cooperatives or cease trading.[5]

Saito’s position dovetails perfectly with the argument for cooperation, or what I call Coöperism, understood as a network of cooperatives, mutuals, unions, and mutual aid. And Saito traces a similar argument in the late Marx: in Marx’s support for communal forms of ownership among the Russian agricultural workers. It is where he ends the book as well: on a call for action that includes worker cooperatives, organic farms, democratization of production, and mutual aid networks.[6] These are signature strategies of coöperism.

In this full-length introduction, I will introduce the late Marx and then turn to Kohei Saito’s formative interpretation.

The Late Marx

The late Marx refers loosely to the final decade (1873-1883) or, sometimes, just the final years (1881-1883) of Marx’s life, the period following the publication of Capital in 1867, the turmoil of the Paris Commune in 1871, and the close of the First International in 1876.

During these last years, Marx is reading and taking copious notes on a range of problematics beyond Western European industrialization and the German, French, and British working class. In the process, he produces a small set of critical writings. Let me go over those in their order of importance.

The Letter to Vera Zasulich (March 1881)

Vera Zasulich (1849–1919) was a Russian revolutionary, living at the time, in 1881, in exile in Geneva, Switzerland, after her assassination attempt, and subsequent acquittal at trial, of the police chief of St. Petersburg.[7] A supporter of the Russian form of communal agricultural property known as “obshchina,” Zasulich wrote to Marx asking him whether he could imagine a path to communism that passed through communal ownership and bypassed Western-style industrialization.

A quick word on the “obshchina,” also referred to in the literature as the “mir.” The obshchina was a form of communal land ownership in Russia by means of which agricultural workers (what are referred to as “peasants”) decided in common how to distribute commonly-held land among different households, what crops to plant, and how to rotate land usage. It amounted loosely to a kind of commune or agricultural worker cooperative. It is believed that the obshchina had its origins in the early 1500s, if not before, and so, predated feudalism in Russia. This form of communal land ownership eventually became the core of rural soviets after the Russian revolution. For the most part, the obshchinas would be dissolved as a result of forced collectivization under Stalin.[8]

Zasulich wrote a letter to Marx dated February 16, 1881, posing a question that she described as “a matter of life or death, especially for our socialist party.”[9] She and her comrades had been fighting over the application of Capital to the political situation in Russia. The question was whether the rural commune in Russia was capable of developing into socialism, in which case the socialist revolutionary had to sacrifice everything to the development of these communes, or whether Russia would have to go through the lengthy and grueling process of industrialization like Western Europe.[10]Zasulich’s letter prompted a deep reconsideration by Marx of his views about possible paths to communism. Marx penned a number of drafts of a response to Zasulich, ultimately cutting down the size of his letter.

In early drafts, Marx suggested that the rural communes would lead to a rejuvenation of Russian society and help create a post-capitalist society superior to those societies that had experienced the domination of capitalism. Marx penned four drafts and the official reply:

- The ‘First’ Draft (4,500 words)

- The ‘Second’ Draft (2,000 words)

- The Third Draft (2,000 words)

- The Fourth Draft (300 words)

- Karl Marx: The reply to Zasulich (350 words)

The final letter that Marx sent is dated March 8, 1881. After apologizing for his delay, Marx begins with two citations from his work, Capital, intended to emphasize that he was only addressing there the situation of industrialized Western European economies.[11]

The first passage of Capital that he quotes is the section concerning, in his words, the analysis of the genesis of capitalist production:

At the heart of the capitalist system is a complete separation of … the producer from the means of production … the expropriation of the agricultural producer is the basis of the whole process. Only in England has it been accomplished in a radical manner. … But all the other countries of Western Europe are following the same course. (Capital, French edition, p. 315.)

Marx thus emphasizes here that he was only analyzing Western Europe. He underscores this: “The ‘historical inevitability’ of this course is therefore expressly restricted to the countries of Western Europe.” And he then writes that “The reason for this restriction is indicated in Ch. XXXII,” which he again quotes for Zasulich. This is the second passage:

Private property, founded upon personal labour … is supplanted by capitalist private property, which rests on exploitation of the labour of others, on wage labour. (Capital, French edition, p. 340).

Marx then concludes with a single paragraph that has received now lengthy treatment. He is writing in French, so I will quote the original text first:

Dans ce mouvement occidental il s’agit donc de la transformation d’une forme de propriété privée en une autre forme de propriété privée. Chez les paysans russes on aurait au contraire à transformer leur propriété commune en propriété privée. L’analyse donnée dans le « Capital » n’offre donc de raisons ni pour ni contre la vitalité de la commune rurale, mais l’étude spéciale que j’en ai faite, et dont j’ai cherché les matériaux dans les sources originales, m’a convaincu que cette commune est le point d’appui de la régénération sociale en Russie ; mais afin qu’elle puisse fonctionner comme tel, il faudrait d’abord éliminer les influences délétères qui l’assaillent de tous les côtés et ensuite lui assurer les conditions normales d’un développement spontané.[12]

In English, this passage reads:

In the Western case, then, one form of private property is transformed into another form of private property. In the case of the Russian peasants, however, their communal property would have to be transformed into private property.

The analysis in Capital therefore provides no reasons either for or against the vitality of the Russian commune. But the special study I have made of it, including a search for original source material, has convinced me that the commune is the fulcrum for social regeneration in Russia. But in order that it might function as such, the harmful influences assailing it on all sides must first be eliminated, and it must then be assured the normal conditions for spontaneous development.[13]

In effect then, Marx argues that based on his own research in those final years, he believes that communal property in Russia can serve as the basis for revolutionary change. We will come back to this.

1882 Preface to the Communist Manifesto

A second key text in the literature on the late Marx is the Russian preface to the Communist Manifesto that Marx and Engels penned and published in January 1882—what is referred to as the “Preface to the Second Russian Edition of the Manifesto of the Communist Party.” That preface as well specifically addressed the question of a Russian revolution and the potential role of the obshchina as a way to bypass industrialization. Marx and Engels write:

[I]n Russia we find, face-to-face with the rapidly flowering capitalist swindle and bourgeois property, just beginning to develop, more than half the land owned in common by the peasants. Now the question is: can the Russian obshchina, though greatly undermined, yet a form of primeval common ownership of land, pass directly to the higher form of Communist common ownership? Or, on the contrary, must it first pass through the same process of dissolution such as constitutes the historical evolution of the West?

The only answer to that possible today is this: If the Russian Revolution becomes the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West, so that both complement each other, the present Russian common ownership of land may serve as the starting point for a communist development.[14]

Here too, then, Marx embraces the idea of communal property as the basis of revolutionary change.

The Critique of the Gotha Program (1875)

Seven years earlier, Marx had famously responded to the Gotha Program, a draft platform for the proposed unification of two workers’ parties, the Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Germany and the General German Workers’ Association, the latter formed by the German socialist politician Ferdinand Lassalle. The platform was associated with Lassalle, an acquaintance of Marx from the time of the 1848-49 revolution in Germany.

In The Critique of the Gotha Program (1875), Marx disparages the Lassallean platform. Marx criticizes the language of the draft for its use of the terms “equal right” and “fair distribution.” Marx argues that the reliance on the concept of “equal right” throughout the text privileges legal relations over economic relations, and that this inverts the relationship between law and economics. This echoes Marx’s argument that law is superstructural or ideological, an argument that we find in the Brussels manuscripts of 1845, known as The German Ideology, and in the 1859 Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Marx asks, rhetorically, “Are economic relations regulated by legal conceptions or do not, on the contrary, legal relations arise from economic ones?”[15] Marx characterizes the notion of “equal right” as nothing more than a bourgeois notion, arguing that it is simply a “bourgeois right” in the absence of an equal labor force.[16]

Marx goes on to argue there that the use of rights language does not appreciate the historical dimension of societal transformation. It does not recognize that there are phases of revolutionary change. In a first phase of communism, Marx argues, there may well be some reliance on the defective notion of “equal right” because many of the new institutions will still be “stamped with the birth marks of the old society from whose womb they emerge.”[17] However, Marx believes that, in a later or a “higher phase of communist society,” there will develop a better understanding of real equality based on abilities and needs. In a fully communist society, there will not be a question of “equal rights”; instead, society will be governed by the principle “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!”[18] In the famous words of the Critique, Marx writes:

In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labor, and therewith also the antithesis between mental and physical labor, has vanished; after labor has become not only a means of life but life’s prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-around development of the individual, and all the springs of cooperative wealth flow more abundantly – only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!

The section from this classic passage that interests Kohei Saito, as a scholar of the late Marx, is the clause “after … all the springs of cooperative wealth flow more abundantly.” For Saito, Marx’s use of the term “cooperative wealth” here indexes communal property and communal wealth. “It seems quite natural to thus read the sentence as referring to the cooperative management of wealth as understood as communal,” Saito writes.[19] He then asks whether the passage suggests, for Marx, that “societal cooperation fostered by communism is modeled on the management of communal wealth in the Markgenossenschaft [the term for the communal social organization of ancient Germanic peoples] and, as such, should be reinstated in Western Europe as well?”[20] Saito phrases this as a rhetorical question. It is clear that the answer is yes.

The Ethnological Notebooks

A fourth important text is comprised of the notebooks that Marx filled while he was reading the anthropological writings of Lewis Henry Morgan, specifically his book Ancient Society, John Budd Phear’s The Aryan Village, Henry Sumner Maine’s Lectures on the Early History of Institutions, and John Lubbock’s The Origin of Civilization. Marx’s unpublished notes and annotations, his excerpts and commentaries, were written during the period 1880-1882. These were compiled by Lawrence Krader and published in 1972. They contain Marx’s last thoughts and comments about primitive accumulation, the formation of the state, and the conception of human beings nested within social relations.[21]

The Marx of the “Late Marx”

Read through the lens of scholars such as Kohei Saito, Marcello Musto, Teodor Shanin, Kolja Lindner, Michael Löwy, Pier Paolo Poggio, Maximilien Rubel, and others—scholars of the “Late Marx”—these final writings constitute a very different Marx than the one that we are accustomed to, especially the Marx of the mature economic writings of Capital, Volume 1.

The traditional Marx is a productivist, economistic Marx, who both critiqued but also praised capitalism for making possible forms of abundance and technological advancement that alone made possible the advent of communism. On this conventional reading, capitalism was the condition of possibility of communism. This is based not only on a reading of Capital but also in part on the Communist Manifesto. Kohei Saito summarizes the traditional view in the following terms:

The advance of capitalism involves the extreme exploitation of workers by capitalists, widening the gap between the rich and poor. Capitalists compete against each other, raising their productivity, which leads to the production of more and more commodities. But workers, exploited due to low wages, can’t afford to buy those commodities. This eventually leads to a crisis of overproduction. The already-exploited workers thus suffer another blow, this time due to the unemployment stemming from this crisis, and rise up en masse, bringing about a socialist revolution. The capitalists are purged, the workers freed.[22]

This traditional reading of Marx was subject to several critiques, including its excessive focus on European industrialization, its valorization of productivism despite the imperialist tendencies of capitalism, and its apparent incompatibility with environmentalism, among other things.

The scholars of late Marx, however, propose a dramatically different Marx. I would call it, perhaps, without the negative connotation, a “revisionist” Marx. It is “revisionist” because, along at least six dimensions, if offers an entirely different reading of Marx—one that absolves Marx of many potential weaknesses:

- First, it is a Marx who is aware of the dangers of climate change. On this reading, Marx was aware of the harm that capitalist methods were inflicting on nature. Marx was reading chemists who were demonstrating the negative effects on soil health. Marx was becoming conscious of the threat of capitalism to the earth.

- Second, it is a global Marx. On this reading, Marx was paying attention to countries outside industrialized Western Europe—to Russia and India, to South America, to indigenous peoples of North America. Marx was concerned about people other than the industrialized proletariat class.

- Third, it is a Marx who is open to alternative paths to communism. On this reading, Marx was considering alternatives to proletarian revolution. Marx was charting a path forward for rural agrarian societies without going through Western-style industrialization.

- Fourth, it is a Marx who is no longer determinist: insofar as he was charting these other paths forward, Marx was also revisiting the progress narrative of historical materialism and no longer wedded to determinism in history.

- Fifth, it is a Marx who embraces cooperatives and cooperation: Marx changes his views on collective ownership and forms of cooperative arrangements, especially with the case of the Russian communes. In this regard, there is a similarity with Lenin who also changed his views at the end of his life, coming to favor cooperatives in his two final essays “On Cooperation” in 1923.

- Sixth, it is a Marx who is less fixated on violent armed revolution. As we saw at Marx 8/13, Engels took a different view of armed struggle after 1849. On this reading, Marx was also forging a slightly different path, especially in the context of Russia.

We can see all this clearly in the work of Marcello Musto, who is perhaps one of the more adamant scholars on these points.

Marcello Musto

Marcello Musto, a professor of sociological theory at York University in Canada, published a book in 2016 in Italian titled L’ultimo Marx, 1881-1883. Saggio di biografia intellettuale. The book appeared in English in 2020 under the title The Last Years of Karl Marx: An Intellectual Biography with Stanford University Press. His book highlights the “late Marx” and proposes several “turns” in the later Marx that reorient our reading of Marx. Those “turns” include:

- An environmental and ecological emphasis: “Recent research […] has shown the importance he attached to the ecological question: on repeated occasions, he denounced the fact that expansion of the capitalist mode of production increased not only the theft of workers’ labor but also the pillage of natural resources.”[23]

- An emphasis on migration and immigration: “He showed that the forced movement of labor generated by capitalism was a major component of bourgeois exploitation and that the key to fighting this was class solidarity among workers, regardless of their origins or any distinction between local and imported labor.”[24]

- A turn to the global and anticolonial: “Marx undertook thorough investigations of societies outside Europe and expressed himself unambiguously against the ravages of colonialism. It is a mistake to think otherwise. Marx criticized thinkers who, while highlighting the destructive consequences of colonialism, used categories peculiar to the European context in their analysis of peripheral areas of the globe.”[25]

- A shift toward cooperatives: “Marx went deeply into […] forms of collective ownership not controlled by the state.”[26]

- A turn as well to “individual freedom in the economic and political sphere, gender emancipation, the critique of nationalism, [and] the emancipatory potential of technology…”[27]

For Musto, the critical task is to displace our attention from the early Marx to the mature and late Marx. Musto is explicit about this. He believes that the late Marx effectively repudiates the young Marx. But not in the way in which Althusser proposed. This is not a philosophical versus scientific break. It is a break that takes us to a non-Eurocentric, post-colonial, environmentalist, and non-productivist Marx.

Musto argues that the mature and late Marx “supersede” the early Marx. They displace less valuable work. Musto is explicit about this. The late Marx is more “precious,” he argues. Musto writes:

For a long time, many Marxists foregrounded the writings of the young Marx (primarily the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and The German Ideology), while the Manifesto of the Communist Party remained his most widely read and quoted text. In those early writings, however, one finds many ideas that were superseded in his later work. It is above all in Capital and its preliminary drafts, as well as in the researches of his final years, that we find the most precious reflections. These represent the last, though not the definitive, conclusions at which Marx arrived.[28]

This is, then, a rehabilitated Marx—rehabilitated from the critiques to which he was subject, from feminists, post-colonialists, ecologists, etc.

Musto is, if nothing else, defensive. Of Marx, he writes, “He was anything but Eurocentric, economistic, or fixated only on class conflict.”[29] Not all scholars of the late Marx, though, are as defensive.

Let us now turn to Kohei Saito’s research and his book, Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto.

Kohei Saito, Slow Down

Kohei Saito’s book rests on several essential foundations. First and foremost, the urgency of the global climate crisis and the extent of the crisis we are facing. This is what grounds and motivates Saito’s entire enterprise. Second, the fact that the global climate crisis is caused by capitalism: for Saito, the ecological crisis cannot be separated from a critique of capitalism. Saito describes the “Imperial mode of living” in late capitalism that has brought us to the point of no return. It is a world of exploitation by the global north of the global south that is dooming all humankind. Third, the fact that most solutions that are being proposed are insufficient. The Green New Deal is inadequate and counterproductive. Saito points out the paradox, for instance, that electric vehicles cause ecological harm because of the need for lithium and the exploitative mining practices in places like the South of Congo. Saito demonstrates that so many of the proposed solutions to global warming are actually counterproductive. Our own efforts at using recycled bags and composting have trivial effects. On Saito’s view, reducing carbon dioxide emissions cannot be achieved while growing our economies, and so, Saito argues, the reduction of emissions can only be achieved through degrowth.

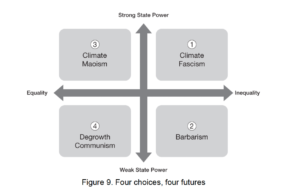

Saito draws a two-by-two chart to capture four possible futures. The X-axis is the level of equality and goes from the most egalitarian positions on the left to the most unequal positions on the right. The Y axis is the concentration of political power in the state, with state power at the top and anarchy at the bottom. Saito describes the four resulting cells, or options: climate fascism top right; barbarism, bottom right; climate Maoism, top left; and what he has in mind, degrowth communism, bottom left.

Double Displacement

Kohei Saito performs a double displacement in Slow Down: he criticizes forms of Marxism that do not take account of global climate change and simultaneously criticizes forms of environmentalism that do not take account of Marxist critiques of capitalism. On this basis, Saito argues for the “common,” a space of shared democratic governance of the commons, as a form of degrowth communism aware of and addressing climate change.

The double displacement is similar to Black Marxism or Feminist Marxism: in both cases, there is a critique of Marxism that does not take account of race or gender; and a critique of race or feminist theories that do not critique capitalism. Degrowth communism has that same double edge: at one end, on the side of degrowth, Saito argues for a degrowth theory that “must clarify its critical position against capitalism.”[30] At the other end, on the side of communism, Saito argues for an ecologically aware, democratic, egalitarian common that opposes itself to an undemocratic state socialism controlled by state bureaucrats.[31]

The book opens with a sharp critique of greenwashing—of all the different efforts to address global climate change within the framework of existing capitalist methods: sustainable development goals (SDGs), or corporate ESG programs, or carbon taxes. He calls these the “opiate of the masses” and critiques them as mere band-aids in the face of climate cataclysm. None of them vigorous enough to combat increasing global temperatures. He builds on Emmanuel Wallerstein’s world-systems theory to show how interconnected the world is, with the core economies dependent on and exploiting the periphery.[32] In the end, he rejects all models that have a growth component.

Saito then explores the writings of Kate Raworth and her doughnut theory of degrowth economics—the idea of placing limits on growth in advanced industrialized countries while allowing the economies of less developed countries to expand so that they achieve minimum standards of health and welfare. Here too, Saito critiques Raworth for failing to take on the problems of capitalism. Saito argues for degrowth coupled with a critique of capitalism: “capitalism’s dependence on externalization and displacement guarantees that it will always work against global justice,” he writes.[33] The heart of the matter, for Saito, is that retaining capitalism will never achieve equality and social justice because capitalism itself is, in his words, “a system that always seeks to open up new markets to accumulate capital and increase value.”[34] Or, as he writes a few lines further, “the essence of capitalism is that it will never stop growing in order to create profit.”[35]

Saito builds on theories of the “common” developed by Michael Hardt, Toni Negri, and others as a third way. (The translation uses “the commons” in the plural, which typically refers to older theories regarding, for instance, the tragedy of the commons or the shared green commons in the center of small towns; by contrast, the newer theories of the common use the term in the singular, so I will keep the singular here, even if it rolls less easily off the tongue). The idea of the common is to create communal property governed democratically by the people—by citizens with equal voice.

Saito argues that Marx gradually came to embrace a theory of the common—understood as the “shared management by citizens in a democratic, equal way rather than leaving administration up to specialists, as advocated by the concept of social common capital.”[36]

In his earlier work, including the Communist Manifesto, Marx believed that capitalist growth and greater production would lead to crises of overproduction and ultimately to the downfall of capitalism and the emergence of socialism. This rested on a progress narrative based on the (double-edge sword) of productivism: capital growth led both to exploitation and domination, but eventually to proletarian revolution and dictatorship.

Saito argues, though, that Marx revised his theories as he witnessed the resilience of capitalism throughout the revolutions of 1848-49, the crisis of 1857, and later, the Commune of Paris in 1871. Marx revised his assumptions, which he tried to present in Capital. But he only published Volume 1. The work, Capital, is unfinished, and the second and third volumes were distorted by Engels. As a result, we do not hear the real or authentic Marx in volumes two and three. Instead, we have two over-edited volumes in which Engels imposed his views on Marx. In order to properly decipher where Marx was headed in Capital, we must look at the last years of Marx’s life—at what he was reading, the notes he was taking, and what preoccupied him.

According to Saito, Marx shifted away from productivism after Capital but that is masked by Engels’ editorial work. Saito writes:

The problem is that this major shift is difficult to detect in the version of Capital currently in circulation. Engels sought to emphasize the systematic nature of Capital and ended up concealing the parts of it that were unfinished. In other words, the parts of these volumes in which Marx grappled theoretically with his analysis were removed from view, as was the very evidence of this struggle. As a result, only the handful of researchers who have studied the research notes Marx kept at the end of his life are aware of this shift in his thinking. This means that even specialized scholars and committed Marxists labor under a misunderstanding of Marx’s ultimate views.[37]

To counter these misunderstandings, Saito points us to Marx’s writings from the late period of his life. These offer a much better guide to where Marx was headed in Capital.[38] They open a window on Marx’s ecological concerns.

Saito points to a passage in volume three of Capital, a sentence where Marx writes about the “squandering of the vitality of the soil.”[39] Saito interprets this passage as Marx “sounding the alarm” about the problems of ecology.[40] Saito argues that Marx saw and predicted the ecological harms, especially in volume III of Capital based on the work of Liebig, Agricultural Chemistry (1862):

Marx warns us in Capital that capitalism opens up an “irreparable rift in the interdependent process of social metabolism.” This is in the section touching on Liebig’s work as he analyzes how large landed property ownership underpins the business of agriculture under capitalism:

[In] this way [large-scale landownership] produces conditions that provoke an irreparable rift in the interdependent process between social metabolism and natural metabolism prescribed by the natural laws of the soil. The result of this is a squandering of the vitality of the soil, and trade carries this devastation far beyond the bounds of a single country.

Marx is sounding the alarm here, in the third volume of Capital, that capitalism will undermine the conditions necessary for sustainable production by disrupting and opening up a rift in the metabolism connecting humans and nature. Capitalism makes the sustainable management of this metabolic connection impossible and thus hinders the further development of society.[41]

In his earlier book, Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism, Saito highlighted that Marx studied the “overharvesting of forestland, the waste of fossil fuels, and the extinction of seeds as arising from the contradictions of capitalism.”[42] Saito suggested there that Marx was evolving towards an idea of a sustainable economic development within socialism, or what he calls ecosocialism.[43]

In his new work, Slow Down, Saito goes further and argues that Marx embraced degrowth at the end of his life. Marx changed his view of communism at the end of his life, a time at which he brought together his research in ecology with his research into communal landowning societies.

According to Saito, Marx’s research in ecology was pointing to civilizational collapse, and his work on communal forms of ownership was pointing to a solution: cooperatives and communes.[44] Marx revises his view of capitalism, suggesting that productivism may not lead to communism, nor to emancipation from class struggle, but instead to the destruction of nature.

This represents, naturally, a radically different way of thinking about capitalism as compared to classic readings of Marx. In fact, it is not clear what one would need to retain or could retain from the classic Marxian view of industrial production. It also entails a different conception of history. As Saito notes, this reading of the late Marx demands that we reassess his earlier views on history as progress, given that capitalism now brings about, not progress but the irreversible destruction of the natural environment and the devastation of society. This shakes the foundations of Marx’s historical thinking. It is no longer evident that Western Europe, with its high level of industrialization and productivity, could be more advanced than the non-Western world.

Saito argues that Marx actually came to favor the sustainable management of land through communal property in Capital, Volume III, in a passage where Marx discusses ground rent and writes: “instead of a conscious and rational treatment of the land as permanent communal property, as the inalienable condition for the existence and reproduction of the chain of human generations, we have the exploitation and the squandering of the powers of the earth.”[45]

This appears even more clearly, Saito argues, in a draft of Marx’s letter to Vera Zasulich, where Marx writes of the necessary “return of modern societies to the ‘archaic’ type of communal property”—which Saito interprets as the argument that “the Markgenossenschaft [communal property] of the Germanic peoples and the mirs in Russia hold within them elements to which the modern societies in Western Europe must return.”[46] On the basis of these draft letters, Saito argues that Marx changed the way he thought about communism in Western Europe.[47]

Of that, I am not entirely convinced. Clearly, Marx was open to another path to communism in a country like Russia, which had not experienced industrialization. But that did not necessarily change the path for Western Europe. He did not include that passage about the “return of modern societies to communal property” in his final letter—perhaps for a reason. In any event, I am not convinced that his late research on Russia extends to his analysis of the West. By contrast, what he was surely suggesting is that in countries like India or Russia, there was the possibility of communal ownership and a steady state economy that would ultimately lead to communism. As Saito writes, “Marx ends up asserting that it’s precisely the steady state of a commune’s economy that allows it not only to resist colonial domination but also to hold within it the possibility of toppling the power of capital and achieving communism.”[48]

On Saito’s reading, though, again, Marx goes further, beyond sustainable growth, to embrace degrowth. Saito’s main point is that, as he writes, “the communism envisaged by Marx late in his life was an egalitarian, sustainable form of degrowth economics.”

Saito makes clear that his unique contribution is to show that Marx went further than ecosocialism. He went further than the idea of a steady state, sustainable economy, or even of a growth economy that is sustainable. He went so far as to embrace the idea of degrowth, as he writes:

No one, though, went so far as to propose degrowth communism. Even in Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism, I stopped at noting how a call for sustainable economic development was part of Marx’s eco socialist thought. […]

But the fact is, Marx’s change of mind after turning away from productivism and concentrating on searching for revolutionary possibility in the study of non-Western and precapitalist communal societies is not just evidence that we should revise the way we imagine him. […]

Rather, it’s evidence that Marx reached the point of imagining degrowth communism as a project that might truly topple Western European capitalism.[49]

In other words, the “real theoretical shift” in the late Marx is to degrowth.[50]

Kohei Saito’s Five Proposals

More concretely, Kohei Saito proposes five steps to promote degrowth communism.

The first is that society needs to shift its production and its attention from high value goods to things that have high use value. By high value goods, he is referring to items that do not really address our needs in times of crisis. He’s referring to value in the Marxist sense of commodity value and to items like luxury goods that have high value in our society. But they have low use value. So basically, he is proposing a shift in consumption and production that would focus on what we need in society to satisfy our most important needs.

The second proposal is to shorten work hours and eliminate wasteful and unnecessary productivity, to get rid of marketing and advertising and packaging, and consultancy and investment banking, to get rid of overnight shipping and 24-hour stores. The idea would be to get rid of facets of the economy that are simply unnecessary to satisfying basic needs. This would allow us to reduce the number of hours that people work across society so that they could enjoy themselves more. The only way that can be done, though, is if there is degrowth or deceleration.

The third proposal is to abolish the division of labor. The idea here is to eliminate specialization and uniformity in what we do. The idea is not to automate and augment creative activities outside work, but instead to make work itself more creative and attractive. The way to do that is to get rid of the specialization and standardization associated with the division of labor. As he writes, “to make work attractive again, we must establish sites of production that allow workers to engage in a wide variety of tasks and activities.”[51]

The fourth proposal is to democratize the production process. This could be achieved by giving workers democratic decision-making power over production and might involve the turn to worker cooperatives, communal management of the means of production, and a commons regime to replace intellectual property rights and monopoly platforms like the GAFAs.

The fifth suggestion is to prioritize labor intensive, essential work. So here, the idea is to move away from, rather than towards, automation and artificial intelligence. Labor intensive work or labor-intensive industries are those that require human labor, for example, care work. That is the kind of work that should be valued in society. It is the kind of work that will decelerate the economy.

In sum, Saito advocates for a shift from high-value to high-use-value goods, reducing work hours, abolishing the division of labor, democratizing production, and prioritizing labor-intensive work, as a way to address the climate crisis caused by capitalism. He emphasizes the insufficiency of current solutions like the Green New Deal and highlights the exploitative nature of modern capitalism, particularly the “Imperial mode of living.” He proposes a return to more labor-intensive industries like care and a reinterpretation of Marx’s later work to focus on ecology and communal property.

Capitalism claims to produce abundance, but in fact, it only creates scarcity, Saito argues. It creates scarcity by enclosing the common and turning it into private property and forms of profit—which then restrict resources. By contrast, Saito proposes to return to and reclaim the common in order to restore what he calls “radical abundance.”

Worker Cooperatives and Coöperism

Kohei Saito urges us to be optimistic about the possibility of change. Fundamental change only requires that a small minority of people rise up in protest. The figure is actually only 3.5%. As Saito writes, “this is the number that Harvard political scientist Erica Chenoweth came up with in the course of her research into protest strategies as the percentage of a population that must rise up sincerely and non-violently to bring about a major change to society.”[52]

On my reading, that major change will take place by means of worker and consumer cooperatives. In his work, Saito argues primarily for worker cooperatives. Worker cooperatives are what return the means of production to the commons. “Workers’ co-ops play a crucial role in workers regaining their autonomy and power of self-determination,” he writes. “Every member of a co-op invests in, owns, and operates the enterprise. It’s the workers who have the agency to discuss and determine what sort of work will be done and how it will take place.”[53]

Worker ownership and democratic self-governance at work are the keystone to achieving the abundance of the common. As I do in Cooperation, Saito discusses the long tradition of worker cooperatives and cooperative ownership going back to the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers in 1844 and forward to the Mondragon cooperatives in the Basque Country today. By contrast to me, Saito aligns Marx with worker co-ops. He refers specifically to passages from Volumes 20 and 22 of the complete works, where Marx describes worker cooperatives as a “possible communism.”[54] Saito discusses that worker coops are becoming more popular, especially within the British Labor Party. He too ties worker co-ops to a solidarity economy.[55] He writes that “workers’ cooperatives can become the basis by which to transform society overall, premised as they are on resisting the impoverishment, discrimination, and inequality fostered by capitalism.”[56]

Saito leans into cooperatives, especially in the context of Barcelona and the movement in Barcelona towards the “Fearless city” for the future. One of the things he notes about the Barcelona is that it is in a particularly good position to clear a path forward because of its “long tradition of workers’ cooperatives there—the very same workers’ co-ops that Marx called examples of ‘possible’ communism.”[57]

It is clear that Saito believes that worker co-ops can pave the way to degrowth communism, and in this context, his work aligns well with a theory of coöperism. “Spain has always been a hotbed of cooperative associations, and Barcelona is famous for its social solidarity economy, which includes not only workers’ cooperatives, but also consumer cooperatives, mutual aid societies, organic produce cooperatives and so on. The social solidarity economy, in fact, employs about 53,000 people, or 8 percent of the people employed in the city, producing 7 percent of the city’s total gross production.”[58] Worker co-ops and coöperism are central to his vision—and this is where Slow Down dialogues with Cooperation—something that we can explore at the seminar!

Welcome to Marx 11/13!

Watch the seminar with Kohei Saito here!

Notes

[1] Kohei Saito, Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto (New York: Penguin Random House, 2024).

[2] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 105.

[3] Wada Haruki, Marx, Engels and Revolutionary Russia (Tokyo, 1975); Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Sur les sociétés précapitalistes, ed. Maurice Godelier (Paris: Les éditions sociales, 2022 (édition augmentée; 1973 édition originale); Karl Marx, The Ethnological Notebooks of Karl Marx: Studies of Morgan, Phear, Maine, Lubbock, ed. Lawrence Krader (Assen, Netherlands: Van Gorcum, 1972).

[4] Marcello Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx: An Intellectual Biography, trans. Patrick Camiller (Stanford University Press, 2020 [2016 in Italian]); Teodor Shanin, ed., Late Marx and the Russian Road: Marx and the Peripheries of Capitalism (Monthly Review Press, 1983); Bruno Bosteels, La Comuna Mexicana (Akal Mexico, 2022); Kolja Lindner, ed., Le Dernier Marx (Toulouse: Les éditions de l’Asymétrie, 2019); Michael Löwy, Pier Paolo Poggio, and Maximilien Rubel, Le dernier Marx, communisme en devenir (Etérotopia, 2018).

[5] Saito, Slow Down, at p. ix.

[6] Saito, Slow Down, at pp. 232-233.

[7] Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx, at p. 53.

[8] See, “Obshchina,” at https://www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/o/b.htm#obshchina.

[9] “Lettre de Vera Zassoulitch à Marx,” in Michael Löwy, Pier Paolo Poggio, and Maximilien Rubel, Le dernier Marx, communisme en devenir (Etérotopia, 2018), at p. 58 (my translation).

[10] “Lettre de Vera Zassoulitch à Marx,” in Löwy, Poggio, and Rubel, Le dernier Marx, communisme en devenir, at p. 58.

[11] All references to “Lettre de Vera Zassoulitch à Marx,” in Löwy, Poggio, and Rubel, Le dernier Marx, communisme en devenir, at p. 60.

[12] “Lettre de Vera Zassoulitch à Marx,” in Löwy, Poggio, and Rubel, Le dernier Marx, communisme en devenir, at p. 58; Karl Marx, “Réponse à Vera Zassoulitch,” 8 mars 1881, available online at https://www.marxists.org/francais/marx/works/1881/03/km18810308.htm.

[13] Karl Marx, “The reply to Zasulich,” 8 March 1881, available online in English here: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1881/zasulich/reply.htm.

[14] Marx and Engels, 1882 Preface, available online at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/preface.htm#preface-1882.

[15] Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program, in The Marx-Engels Reader, 2nd ed., ed. Robert C. Tucker (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978), p. 528; also available online at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/ch01.htm.

[16] Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program, p. 530.

[17] Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program, p. 529.

[18] Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program, p. 531.

[19] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 125.

[20] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 125.

[21] See generally “Introduction” in Karl Marx, The Ethnological Notebooks of Karl Marx: Studies of Morgan, Phear, Maine, Lubbock, ed. Lawrence Krader (Assen, Netherlands: Van Gorcum, 1972).

[22] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 91.

[23] Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx, at p. 3.

[24] Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx, at p. 3.

[25] Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx, at p. 3.

[26] Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx, at p. 3.

[27] Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx, at p. 3.

[28] Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx, at p. 4 (bold added).

[29] Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx, at p. 4.

[30] Saito, Slow Down, at p. xii.

[31] Saito, Slow Down, at p. xii.

[32] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 112.

[33] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 65.

[34] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 69.

[35] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 69.

[36] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 87.

[37] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 93.

[38] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 92.

[39] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 98.

[40] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 98.

[41] Saito, Slow Down, at pp. 97-98.

[42] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 99.

[43] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 101.

[44] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 110.

[45] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 116, quoting Marx, Capital Volume III, at p. 948-949.

[46] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 117.

[47] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 118.

[48] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 119.

[49] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 123.

[50] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 118.

[51] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 195.

[52] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 231.

[53] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 163.

[54] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 164.

[55] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 165.

[56] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 166.

[57] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 212.

[58] Saito, Slow Down, at p. 212.

© Bernard E. Harcourt. All rights reserved.