In an essay on Genet published in Grand Street, Edward Said tells the story of leaving Hamilton Hall to see Genet speak (on the steps of the Low Library) at a rally for the Black Panthers in the spring of 1970, with the university having yet to recover from the student protests of 1968. Said noted about Columbia that at that time “its administration was feeling uncertain, its faculty were badly divided, its students were perpetually exercised both in and out of the classroom.” At the Panther rally, Said observed a great difference between “the declarative simplicity of Genet’s French remarks” and “the immensely baroque embellishment of them by my erstwhile student.” [Continue reading…]

Yearly Archives: 2023

What are the stakes today in revisiting the mid-twentieth century debates between Franz Neumann, Friedrich Pollock, Otto Kirchheimer, and Ernst Fraenkel over the concept of “state capitalism” and their analysis of National Socialism as a totalitarian economic regime – other than matters of historical interest? The discussion at Coöperism 8/13 highlighted at least three. [Continue reading here…}

Coöperism 8/13 returns to the mid-twentieth century debates over state capitalism, and, more specifically, to the lively debate within a circle of expatriate German thinkers over the rise and establishment of National Socialism under Adolf Hitler. Among these German thinkers were the labor lawyer and political theorist Ernst Fraenkel (1898-1975) and several members of the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, including Otto Kirchheimer (1905-1965), Franz Neumann (1900-1954), and Friedrich Pollock (1894-1970), who moved to Columbia University during the war as part of the Frankfurt School in exile. The rise of National Socialism in Germany during the 1920s and 30s presented a puzzling challenge to the conventional opposition between free market capitalism and state-controlled planned economies. [Continue reading here…]

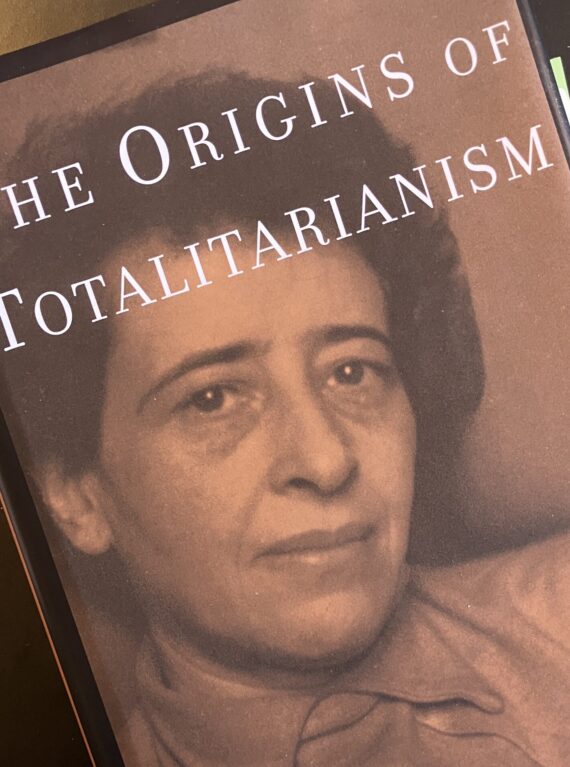

By contrast to Franz Neumann, who characterized the Third Reich as lawless and chaotic, a “non-state” in his words, and to Ernst Fraenkel, who identified both a rule bound and lawless dimension to what he called the “Dual State,” Hannah Arendt argued that totalitarian forms of government (including both Nazi Germany and Stalinist USSR) disregard positive law but aspire to a higher law. For Nazi Germany, Arendt describes that higher law as “the law of nature,” by which she means the white supremacist belief in the superiority of the Aryan race as a matter of genetic science. In the case of the Soviet Union under Stalin, Arendt described the higher law as “the law of history,” understood as a historical materialist theory that inextricably led to the dictatorship of the proletariat, or in her words the superiority of a class. We have seen this played out recently in American politics: political leaders claiming that the enforcement of positive law is purely political and being weaponized, and should give way instead to a popular conception of what is right. [Continue reading here…]

When Max Horkheimer took the reins, in 1931, of the Institut für Sozialforschung, the critique of capitalism received an unexpected jolt. His directorship of the fêted think tank marked a turning point in the development of critical theory. For Horkheimer streamlined the nascent Frankfurt School. He saw to it that staff trained their eyes on varieties of capitalism.[2] In Germany and later at Columbia University, he cultivated an “interdisciplinary materialism.”[3] For the best part of a decade, the critique of advanced capitalism was the overarching focus of the Institute for Social Research. [Continue reading here…]

Ernst Fraenkel’s 1927 essay Zur Soziologie der Klassenjustiz (‘On the sociology of class justice’) had disparaged social-democratic trust in German law as a site for political reform. The law, he contended there, could not be understood in abstraction from its actual practitioners who were, after all, endowed with a specific class position. Franz Neumann, too, sought to point to the necessity of rethinking the law from its liberal foundations. In his Behemoth (1942), Neumann would chastise Social-Democracy for its ‘complete reliance on formalistic legality’ and its inability — or outright reluctance — to ‘root out the reactionary elements in the judiciary’. But more than this: According to Neumann, the parties supporting the republic had relied too much on an easy pluralism which sought to dissolve sovereignty and the unity of the state into a system of plural stakeholders in constant negotiations. This strategy had kept Social-Democrats outside of the real centers of power: the army, bureaucracy, the judiciary and, crucially, industry itself. It had given their political successes in labour law and social legislation a fragile character without robust political backing. [Continue reading here…]

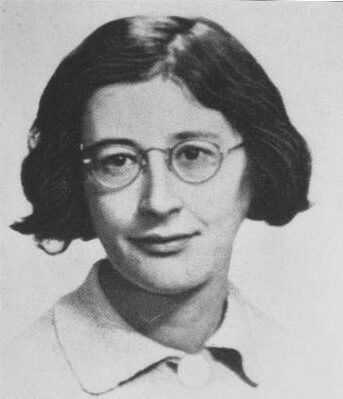

In his brilliant book, Simone Weil’s Political Philosophy: Field Notes from the Margins (2023), Benjamin Davis reads Simone Weil as an important political philosopher. Weil was one of the first thinkers of European descent to call into question her own country’s colonial practices. Clearly, many intellectuals have done the same, however, they do not acknowledge that Weil was the first to do so. For interrogating her culture and society on those anti-colonial grounds, many dismissed her as crazy. Many also dismissed her by focusing on her strange practices of eating and dressing. Ben shows that, if we focus on reading Weil, for the depth of her thinking—that is, if we read Weil as a political philosopher—then we can get a sense of the insights that she offers us. Those insights include: (1) a concern that Western societies have raised their nations to the level of Gods as objects of worship; (2) a method that involves living with workers and those marginalized and exiled if we are truly to understand the modern categories we live under, such as citizen, democracy, fascism, revolution, and exile; and (3) an adamant belief that philosophy should be understood as a way of life, as something that we practice in how we dress, eat, write, speak, and treat one another. [Continue reading here…]

Commemorations of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Institute for Social Research—the Frankfurt School—have taken place around the world this year, many of them at prestigious universities and featuring key contemporary representatives. My general impression of those events is that they have neglected a crucial and still relevant conjuncture in the Institute’s history. That neglect points to some unfortunate lacunae within more recent Frankfurt-oriented critical theory.. [continue reading here…]