By Bernard E. Harcourt

In his victory speech the night of his election, Zohran Mamdani invoked two great figures from history, Eugene V. Debs and Jawaharlal Nehru. The first, Eugene Debs, is perhaps the most famous Socialist in American history. The second, Nehru, was the leader of the most populous, post-colonial, independent nation in the world, India. Together, Debs and Nehru symbolize the dawn of a new political era of cross-cultural solidarity. Mamdani summons these two world-historical figures to ring in a new epoch in American politics.

Mamdani’s speech, drafted by Julian Gerson with Mamdani’s major input, uses the metaphor of “hands” to introduce this new political era. First and foremost, he depicts working hands—toiling hands, scarred and blistered by repetitive use: “Fingers bruised from lifting boxes on the warehouse floor, palms calloused from delivery bike handlebars, knuckles scarred with kitchen burns.” Second, and relatedly, he suggests that these working hands have never been allowed to hold power—to get their hands on power. But third, and most importantly, he declares that these working hands have now, finally, grasped power. “The future,” Mamdani proclaims, “is in our hands.”

The metaphor of hands fits perfectly Mamdani’s underlying theory of social struggle. He grounds his politics in a societal struggle between those who work, most often with their hands, and those who merely profit or take advantage of the hard work of others—between those who work in the city but cannot even afford to live there and those who live in the city without even needing to work.

But Mamdani does not leave matters there. He augments and enriches the class division by invoking the postcolonial struggle—epitomized by Nehru—and blends in the categories of race, ethnicity, gender, national origin, and religious background. Those who have been excluded are not just the working class, they are Muslims, Black New Yorkers, persons of color, and working women as well. Mamdani refers to the “Yemeni bodega owners and Mexican abuelas. Senegalese taxi drivers and Uzbek nurses. Trinidadian line cooks and Ethiopian aunties.”

Together, the working class, post-colonial, and global dimensions offer a novel theory of social struggle that reaches across, but also beyond the five boroughs. This was, of course, a municipal election. But Mamdani’s success has national, even international implications. It represents a victory over President Donald Trump, over the leadership of the Democratic Party, and over the Democratic Party establishment (represented by former governor Andrew Cuomo). President Trump weighed in heavily during the campaign, threatening New Yorkers with retribution if they elected Mamdani. The leaders of the Democratic Party in the House and Senate only reluctantly and belatedly endorsed Mamdani, even after he won the Democratic nomination. The powerbrokers and financiers of the Democratic establishment spent millions of dollars supporting Cuomo, who was not even running as a Democrat. Mamdani’s victory is a rebuff to President Trump—the equivalent of a midterm reversal—but also to the Democratic Party establishment. There are international implications to his victory as well, especially for positioning a new Left in countries around the world that are experiencing a political slide to the far Right.

Mamdani is a sophisticated theorist—as evidenced by his victory speech, but also by his time on the campaign. He studied critical theory at Bowdoin College, an excellent liberal arts college in Maine, read Frantz Fanon, learned about the Haitian Revolution, delved into problems of urban crises, majored in Africana studies. He also grew up in a home of brilliant intellectuals.

As a result, critical theoretic dimensions play an important role in his vision of the world. He is not only a savvy young politician, an eloquent speaker, and an astute strategist, he is also an engaged and cutting-edge political philosopher. In this regard, I would like to suggest, he instantiates what might be called “a new philosophical practice.”

I’ve argued elsewhere that Zohran Mamdani is a model of a politician who offers a positive and clear vision of where he wants to lead society and provides well-defined policy proposals to support his political vision. During his campaign, Mamdani kept his eyes on the prize: he charted a clear and positive vision to make New York City more affordable for everyone who lives there. He did not engage in negative campaigning. He did not trade in negative messages. Instead, he constantly offered a constructive vision and program. It was never just “No Kings,” it was a positive vision and precise public policies that everyone knew: rent stabilization; free buses; universal child care; city-owned grocery stores; community response teams; and more.

But Mamdani is also the model of a political actor and thinker who is engaged in a new practice of philosophy. He is a critical theorist/political actor who is constantly confronting concrete political projects with philosophical principles, and vice versa.

In my last essay, I argued that there is an urgent need, today, to develop a new philosophical foundation for the Left. I proposed a different paradigm than the usual categories of capitalism and socialism: a bottom-up model of cooperation and solidarity that builds on worker and consumer cooperatives, mutuals and mutual aid, and other forms of solidarity economies. It is a model in which the people retain power, rather than concentrating it in the hands of the State.

In this essay, I would like to add that the Left also needs a new philosophical practice. It is not just a question of the philosophy itself, which must always be in motion, constantly revised and revisable—thought in action and in movement (this is perhaps the greatest debt we owe to a thinker like Hegel and his dialectic). It is also a question of a new philosophical approach: one that is politically engaged and accompanies action. That is key: to engage in theoretical work that takes political sides, draws sharp demarcations, and operates hand-in-hand with political actors to enrich politics. The Left needs theorist/political actors on the model of Zohran Mamdani.

To sketch out what I have in mind, I will draw on the writings of the postwar French philosopher Louis Althusser, who, throughout his deeply problematic and troubled life, constantly struggled to provide the Left with a philosophical foundation and, in the process, developed one model of what he called “a new philosophical practice.”

Now, returning to Althusser is problematic for many reasons, most importantly because he murdered his wife, Hélène Legotien Rytmann, in November 1980. That act must affect our understanding of him and his work—and does, as I will show. It raises difficult questions about Althusser and about his philosophical practice. These are difficult questions. But we should not shy away from them.

Louis Althusser’s Relationship to Philosophy

From the mid-1940s to the late 1960s and into the 1970s, Louis Althusser dedicated his intellectual life, his intellectual quest, to one question: How to provide a philosophical foundation to the Left. Althusser was haunted by his concern that the Left, by which he primarily meant Marxism, lacked a philosophical basis. And so, he made it his task to seek out theoretical foundations to enrich and empower the Left.

This task motivated his entire intellectual journey, and the answers that he provided over the course of his life varied greatly. They ranged from one extreme to another. Althusser started by searching for Christian foundations, and then turned to Hegel’s philosophy and dialectics, but eventually discarded Hegel and Christianity completely to develop a secular revolutionary foundation that he located in Lenin’s philosophical practice.

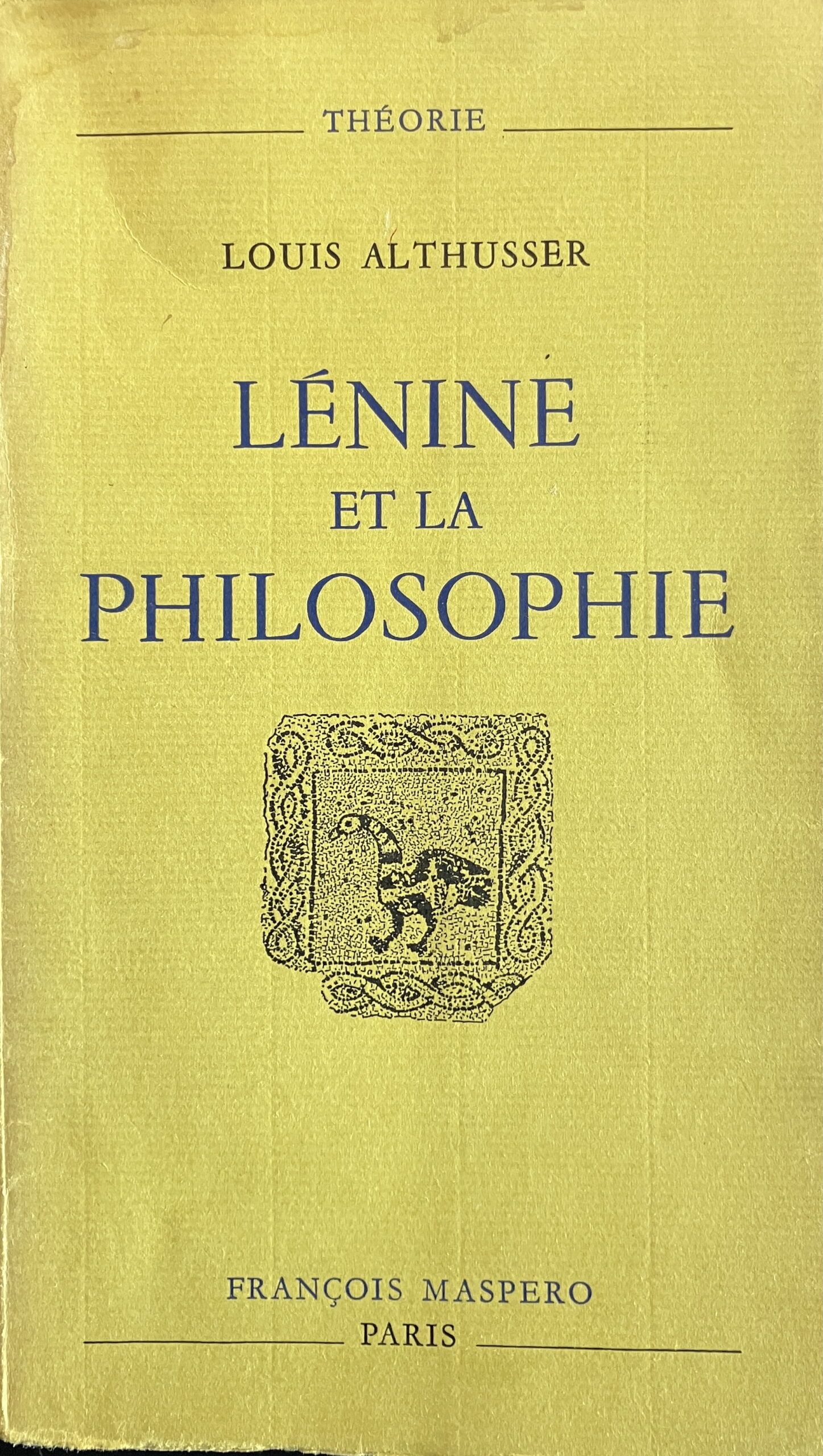

I am most interested here in those later writings from 1968-1969 concerning what he called a “new philosophical practice,” so I will dive right into that for the moment, and come back later to his other proposals—false starts or missed opportunities—as well as his deeply problematic biography.

The reason that Althusser ultimately looks forward to Lenin and other revolutionary thinkers, rather than backwards to philosophers like Hegel, Kant, or Fichte, or even further back to the Christian fathers, is that he came to the view that Marx had inaugurated a new scientific domain. He called it the “science of history.” And he maintained that it would give rise to a new way of doing philosophy. That new way had not yet been invented or discovered by the time of Marx’s death, but was on the horizon and already announced by Marx in his famous eleventh thesis on Feuerbach: the idea of a new philosophy that would not just interpret, but transform the world.

Althusser argued that the discovery of new scientific domains had always come first, and was only later accompanied by new philosophical approaches. He maintained that there had only been three such scientific domains opened in human history, and that they each had or would be followed by a new philosophical approach. According to Althusser, the ancient Greeks launched the first scientific “continent,” in his words, with the discovery of the science of mathematics.[1]That scientific domain would give rise to Plato’s philosophy. Galileo discovered the second scientific domain, the science of physics, and that eventually gave birth to the philosophies of Descartes, of Kant in response to Newtonian physics, and eventually to Husserl. Althusser argued that Marx inaugurated the third of only three scientific domains, the science of history—before it, there were only philosophies of history—but that he had not developed the accompanying philosophy other than to signal that it entailed an epistemological break articulated in the eleventh of his Theses on Feuerbach.[2]

That, according to Althusser, was the very meaning of the eleventh thesis: namely, that a new philosophical approach was necessary and necessarily entailed by the new science of history. But Marx did not have time to develop this new philosophical approach, or to write the book on the dialectic that he had promised. Instead, Marx dedicated himself to the scientific enterprise that led to the publication of the first volume of Capital in 1867.

This interpretation is in keeping with Althusser’s more well-known thesis, from the mid-1960s, that there is an epistemological break in the writings of Marx between the earlier philosophical and Hegelian writings pre-1845 and the later mature economic and scientific writings that led to Capital. Althusser famously argued that Marx’s work became scientific after 1845 and that the earlier philosophical writings should be discarded as still purely ideological. That scientific work would lead, according to Althusser, to one of three scientific discoveries in human history—the science of history.

The Implications for Philosophical Practice

Althusser believed that each scientific domain would give birth to a new philosophical approach. In the case of mathematics, it was platonic philosophy. In the case of Galilean physics, it was the philosophy of Descartes, and later Kant, and Husserl. But the scientific domain of history had not given rise to a new philosophical approach by the time that Marx died. And philosophy always comes late on the scene, as Althusser intimated, with a silent nod to Hegel’s famous aphorism about the owl of Minerva rising at dusk—meaning that wisdom is always achieved late in the game.

Althusser and others, Lenin especially, searched for philosophical foundations to Marxism in Marx’s magnum opus, Capital, Volume One. That motivated Althusser’s work in Reading Capital, a collective work with his students, Étienne Balibar, Roger Establet, Pierre Macherey, and Jacques Rancière, published in 1965. But—at least, this is my sense—Althusser did not feel that he found what he was looking for there, and so he continued searching after 1965. But he continued to search, not by going back in history to the pre-scientific era, but instead by going forward in history toward those who were part of the scientific paradigm—to borrow a Kuhnian term. It is for this reason that Althusser would spend so much time searching for philosophical foundations in the writings of political actors who put Marx’s words into action—not only Lenin, but also Mao, whose essay On Contradiction would serve as primary material for Althusser, as well as, for a while, at least until his name was no longer mentionable, Stalin and his essay on Dialectical Materialism and Historical Materialism.

Althusser’s confrontation with Lenin and with Lenin’s relationship to philosophy—which, for Lenin, as we saw earlier, included a deep dive into Hegel’s Logic in 1914-1915—destabilized his own views in the late 1960s and led to what he would call an “autocritique” of his earlier position from 1950, a time at which he evacuated Hegel.

In a lecture that he delivered to the French Philosophical Association in February 1968 titled “Lenin and Philosophy,” and in another presentation he made a year later in April 1969 called “Lenin Before Hegel,” Althusser brought Hegel back into his interpretation of Marx, arguing that the main debt that Marx owed Hegel was the central idea of history being a “process without a subject,” by which he meant without a human subject, without individual humans as agents. The agents of history, Althusser would argue, are the masses—not individuals.

Althusser remained convinced that there had been an epistemological break in the work of Marx, which meant that he still effectively evacuated the writings of the young Marx and with them, the Hegelian and other philosophical influences on the young Marx. Despite that, Althusser now acknowledged that the late Marx drew on Hegel’s system. Marx drew on Hegel’s Logic and on the second part of the Encyclopedia namely on the dialectics of nature—which are non-human processes—to develop the idea of a “process without a human subject.” That notion of process grounded Marx’s work in Capital, Althusser claimed. It also gave rise to the need for a new philosophical practice, since all prior philosophies were purely descriptive or diagnostic, but did not seek to change the world.

This is what then opens the door to the search for a transformative, rather than merely interpretive philosophy. It also explains why Althusser was so concerned that there was a philosophical vacuum in Marxism that needed to be filled—that is, after the science of history was born.

In 1968 and 1969, Althusser fills the void by returning to Lenin, to Lenin’s relationship to philosophy, and to what Althusser called Lenin’s “new practice of philosophy.”

Before getting to that, though, let me just return for a moment to the wide-ranging nature of Althusser’s other efforts to uncover a philosophical foundation for the Left. The French philosopher Jean-Baptiste Vuillerod does a masterful job of elaborating these earlier moments in his book on The Birth of Anti-Hegelianism, published in 2022.[3]

The Young Althusser

In his first writings from 1946, Althusser tried to infuse Christian ideas into Leftist thought. At the time, Althusser was still of Catholic faith and had just spent five years as a prisoner of war in a Germany stalag. Resuming his studies in philosophy at the age of 28, now at the ENS, Althusser argued that the Christian notion of destiny could serve as a foundation for the workers movement.

At the time, Althusser was writing against the leading intellectuals of the moment, moderate Leftists such as André Malraux and Albert Camus, who embraced a doomsday view of the future of mankind—a time marked by the atomic bomb, the risk of nuclear war, and the apocalyptic conditions in post-war Europe. Althusser argued that their doomsday view of destiny was a deliberate subterfuge: it allowed them to present as self-styled humanists advocating for consensual politics, but at the same time, it allowed them to reject the workers’ movement. Their humanism elided the real differences that existed in the social condition of the working class.

Althusser advanced instead a Christian notion of destiny as human progress and self-development, and linked that idea of destiny to the workers’ movement. In effect, without saying as much, Althusser tied together the eschatological dimensions of Christianity and of Marxism. But he quickly moved away from that position and from Christian teachings.

The following year, in his masters’ thesis, Althusser turned instead to Hegel’s philosophy to ground his Leftist politics. Although Hegel’s early notion of destiny from his 1799 essay The Spirit of Christianity and Its Destiny had been mentioned in 1946, Althusser gives it a far more central place in the first part of his thesis in 1947; but following that, Althusser turns primarily to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit and Logic as his main sources to enrich Marx’s writings. Althusser develops a hypothesis that essentially cycles between Hegel and Marx to show how they complement each other, add to each other, and lead ineluctably to a revolutionary dialectic that is embodied by the workers’ movement.

If, at an earlier time, he was drawing on the revolutionary aspects of Christianity, at this point Althusser is drawing primarily on the revolutionary aspect of the dialectic in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, which, as you will recall, ended with the French Revolution, the Terror, and the revolutionary aspects of citizenship in a supposedly rational bureaucratic Empire.

Only three years later, Althusser sheds entirely his Hegelianism. In a fierce critique of his peers published in 1950 under the title “The Return to Hegel: The Last Word of Academic Revisionism,” he accuses French university philosophy professors of rediscovering Hegel in order to undermine the workers’ movement and Marx’s legacy. The Hegelianism that had come to dominate professional philosophy in the French university, Althusser argued, was complicit with the fascist attacks on the working class. Althusser treats the renewed interest in Hegel as a reactionary political ploy. “This Great Return to Hegel,” he writes, “is nothing more than a desperate recourse against Marx, in the specific form that revisionism takes at the moment of the final crisis of imperialism: a revisionism of a fascist character.”[4]

In the process, Althusser, who by 1950 had evacuated Christian thought and also renounced Hegelianism, is left only with Marx—and his nagging sense that Marxism lacks a philosophical foundation. From that point on, Althusser searches for philosophical foundations not only in the book Capital, but in later thinkers and political actors who would work within the paradigm that Marx opened. This is what leads him to Lenin.

In effect, Althusser’s evacuation of Hegel allowed him to search forward, rather than backwards, to find a philosophical practice for Marx’s science of history. It opened an entirely new, forward-looking vista.

Lenin’s “new philosophical practice”

What does it consist of? According to Althusser, it had two main features:

First, it consists in creating clear lines of demarcation within theory. As examples, one could think of—although Althusser does not mention it—his own theory of an epistemological break between the young philosophical Marx and the mature scientific Marx. Or, one could think of Althusser’s earlier sharp demarcation, in his 1947 thesis, between the early Hegel of The Phenomenology of Spirit (1806) and the Logic (1812-1817) on the one hand, and the late Hegel of the Philosophy of Right (1820)—in that case, he argued that the late Hegel should be evacuated. Or, one can think of—Althusser gives this example—the way in which Lenin decided to read Hegel as a materialist. Those are all examples of sharp demarcations.

Second, it consists in taking sides in the current political struggle, more specifically, in taking sides with the workers in class struggle. It means rejecting the idea that one can or must be objective or neutral in one’s philosophical judgment. Practicing philosophy for Lenin, according to Althusser, means taking a political position.

In this, Michel Foucault’s and Althusser’s thinking would begin to align again in the post-May ’68 turmoil. Foucault had studied with Althusser and been mentored by him during his time at the ENS in the late 1940s, and they saw eye-to-eye on politics during the early 1950s—it was Althusser, reportedly, who encouraged Foucault to join the French Communist Party. But they had grown apart intellectually, I would say, at least until this period. By the Spring of 1973, in his lectures at the Collège de France on The Punitive Society and his conferences in Rio on “Truth and Juridical Form,” Foucault too was attacking the idea that knowledge could be divorced from politics. That great myth—namely, that knowledge can only achieve truth when it is cleansed of politics—has to be “liquidated,” Foucault exclaimed in Rio. For Foucault, it was Nietzsche who began to set things straight—but it was up to us, now, to do the work he had started. This would give birth to Foucault’s theory of knowledge-power and, eventually, his genealogical method.

If Foucault turned to Nietzsche in the late 1960s—with his lectures on Nietzsche at the experimental campus at Vincennes in 1969-70—Althusser, for his part, turns to Lenin instead. The second feature then—for both Althusser and Foucault at the time—is that philosophical practice demands that the philosopher take sides.

A New Practice of Philosophy for Today

I believe that this new practice of philosophy, which Althusser was trying to sketch out, could serve as a guide for us today. It would have several important implications.

First, it means that philosophical practice is conducted hand-in-hand with engaged political actors who are committed to transforming society—more so than with professional philosophers or university professors. Trained philosophers do not have a monopoly on philosophical practice. On the contrary, their training gives them tools and concepts to engage political actors and work in tandem with them. Insofar as political actors have taken sides and are genuinely trying to transform society, they are ipso facto engaged in philosophical practice and bring as much if not more to the table.

Second, it means that philosophical practice does not deal in abstractions and should not operate in a bubble or in isolation. The model is not the brain in a vat or the duality of mind and body. On the contrary, philosophical practice must engage the concrete, real problems facing ordinary people. It must tend toward solutions, by which I mean political theories, visions, and horizons, as well as punctual practices, strategies, and policies.

Third, it means that philosophical practice is not primarily or does not limit itself to diagnosing crises and conjunctures, nor is it about building intricate philosophical systems that describe the world. Instead, it aims to have an impact on society, to work through existing political practices to transform society. It is ambitious in that sense. It works with political movements, not merely theorizing what is going on, but using thought to help orient action—and vice versa.

At the same time, fourth, trained theorists are companions, not the avant garde. Philosophers are not intellectuals leading a revolution, but rather, contribute to political transformation by confronting theory and practice. There needs to be an alliance, an integration of theorists and political actors, of thinking and doing. Political change is led by ordinary people acting in collectivity. The philosophical practice should be incorporated in social movements and politics.

Fifth, and returning to basics, it means that philosophical practice takes sides. It is politically engaged and thus, marked. It does not try to, nor believes that it would even be possible to be neutral, to be objective, to be an arbiter or judge. It is instead committed to the values and politics of the Left—to solidarity, to cooperation, to equality and emancipation. It is a philosophical practice of the Left.

Sixth, and finally, it is a philosophical practice that reaches forward rather than backwards. That too is fundamental for the Left. It is the opposite of “conservatism,” which looks to the past.[5] The practice must look forward, onwards, en avant. It is not a return to the old systems of Hegel, Kant, or Fichte, but a movement into the future.

In an interesting way, Althusser’s break with Hegelianism in 1950 provided the opening to explore a new philosophical practice. His fierce critique of the “Return to Hegel” forced him to look forward, not back—with a very promising and hopeful attitude. It opened the door to forward-looking practice. For Althusser, this was the product of Marx discovering a new science of history, which would entail a new philosophical approach, with philosophy always coming later, like the owl of Minerva. Thought takes time.

For us, today, this approach can help orient a new philosophical practice forward. Onwards.

Let me try to demonstrate how by returning to Zohran Mamdani, his victory speech, and more generally, his campaign. I will also discuss another political actor, Bernie Sanders, and study not a prepared text, but his free-flowing recent interview with the New York Times correspondent, David Leonhardt.

Louis Althusser’s Murder of Hélène Legotien Rytmann

Before proceeding, though, I would like to address the question of Althusser’s biography, specifically Althusser’s murder of his wife, Hélène Legotien Rytmann. Hélène Rytmann always receives little attention in these discussions, so the first thing I would like to do is refer the reader to recent work that begins to conduct serious archival biographical work on Rytmann.[6]

The murder of Hélène Rytmann on November 16, 1980, which is now recognized by many, correctly, as femicide, raises a number of controversial issues surrounding the biography and work of Althusser—and has led some people to cancel him. I cannot address every aspect of this, so I will limit myself to its implications, as I see it, for how we should treat Althusser’s work.

Some background is important first. From the moment of the murder of Hélène Rytmann, Althusser was protected by his peers, friends, and students at the ENS and in Paris, and by the ENS, as an institution, itself. He was immediately transported to a mental hospital, rather than a police precinct, and was swiftly determined to be mentally ill at the time of the murder. He did have a long history of mental illness dating back at least to his time in the German stalag, and had been institutionalized on a number of occasions and subjected to severe psychiatric interventions, including electroshock therapy, decades before the murder. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the 1940s already and had manic bouts throughout those decades. By 1980, he was in a terrible mental condition. So it is not as if there was no basis at all for questioning his sanity at the time of the crime. But there is no question that he benefitted immensely from his privilege as a well-respected philosopher at the ENS, which served to protect him from any criminal responsibility or penal sanction. He was institutionalized for a couple of years following the murder, but also benefitted from his privilege by eventually being released and living freely, before being institutionalized again at the end of his life.

What is clear is that Hélène Rytmann had been an intellectual partner and had supported his work and writings throughout their decades-long marriage, and that Althusser would not have been the philosopher that he was without her support.

What this suggests is that his various philosophical interventions, over the course of his intellectual career, were partly the product of her labor and support. So, for instance, the very argument about the need for a new philosophical practice was itself made possible by gendered power relations and hierarchies—as well as other social structures and advantages that Althusser benefitted from as a comfortable, well-connected, salaried white man teaching at the ENS, who was not himself really part of the working class. The ideas that emerge, thus, are the product of gendered and other privileges and social hierarchies—some of which, at least class hierarchies, Althusser was trying to combat.

This should chasten the way that we think about abstract philosophy, about theory or thought, about thinking, because for Althusser all of those activities were made possible through gender, class, and other forms of privilege—through forms of social hierarchy that make it possible to spend one’s time thinking and not doing, not working with one’s hands. As a result, we need to trim the sails on the very idea of a “new practice of philosophy.” We might want to bring the very word philosophy down one notch, down to scale. Perhaps we should be thinking about new practices of thinking, more modestly. Maybe it’s just critical thinking rather than august philosophy, or theory rather than philosophy, that we should be talking about. According to Lenin, the whole of philosophy has always been a struggle between idealism and materialism, between theory and practice; perhaps this is another reflection of that insight. In the end, this does not mean that we get rid of theory, but maybe we cut it down to size a bit more.

Victory Speech and Interview with Sanders

The challenge, then, is to reread to Zohran Mamdani’s victory speech or Bernie Sanders’ interview to explore how they reflect a new practice of critical thought in relation to action.

Mamdani first. The overarching theme of the victory speech he delivered at the Paramount Theatre in Brooklyn the night of November 4, 2025, is that the election represents a new political era. “Tonight we have stepped out from the old into the new,” Mamdani exclaims. The election represents the dawn of a new era, and Mamdani enlists Eugene Debs and Jawaharlal Nehru to motivate the new era.

Debs symbolizes American socialism and hope: the beginning of a new era, the beginning of a new politics. Debs helped found several socialist parties in America—including the Social Democracy of America Party in 1897, the Social Democratic Party of America in 1898, and the Socialist Party of America in 1901—and ran as a Socialist candidate for President five times, the last time from prison, where he was incarcerated for speaking out against the First World War. Debs is probably the best known American socialist in history. Mamdani called on him at the very opening of the speech, quoting him saying “I can see the dawn of a better day for humanity.”

Nehru symbolizes the anti-colonial struggle against imperialism and the founding of a new era, a new country, and a new government characterized by social democratic politics. Nehru was a main comrade to Gandhi and became the first Prime Minister of India, serving from 1947 to 1964—and was also an author and intellectual. Mamdani invoked Nehru a few minutes into his speech, quoting him saying: “A moment comes, but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”

Referencing both Debs and Nehru together is philosophically significant. The first represents the more traditional socialist embrace of the working class, the second the more contemporary appeal to decolonization and the emancipation of subjugated peoples. Mamdani is not merely introducing identity politics into class struggle, as so many before him have tried to do—so often resulting in tension or competition between class and race or gender. Instead, Mamdani is trying to bridge or reconcile the emancipatory ideals of both into a fused vision of a new era.

The result is a powerful statement about a new dawn. “This new age will be one of relentless improvement,” Mamdani claims; and he then substantiates the claim: stabilizing rents, providing free universal child care, making bus transportation free, hiring more teachers, improving conditions in public housing, creating community responders, and more.

Mamdani self-identifies as a democratic socialist. He does not present himself merely as a social democrat, but explicitly as a democratic socialist. “I am a democratic socialist,” he exclaims. “And most damning of all, I refuse to apologize for any of this.” In this, Mamdani is proud, and radical. He embraces radicality rather than convention. In fact, it is convention that has, in his view, set back the Democratic Party and resulted in the erosion of the working-class base of the party. “Convention has held us back,” Mamdani explains. “We have bowed at the altar of caution, and we have paid a mighty price. Too many working people cannot recognize themselves in our party, and too many among us have turned to the right for answers to why they’ve been left behind.”

Throughout his speech, there is a recurring image of a struggle between the working poor and the wealthy: On the one hand, there is the working class, the poor, those who actually do the work, and who find themselves without resources, having to live two hours outside of New York. And on the other hand, there are the wealthy people who have all the power and are taking advantage of the workers. “As has so often occurred, the billionaire class has sought to convince those making $30 an hour that their enemies are those earning $20 an hour,” Mamdani says. “They want the people to fight amongst ourselves so that we remain distracted from the work of remaking a long-broken system. We refuse to let them dictate the rules of the game anymore. They can play by the same rules as the rest of us.”

Mamdani’s plan is to reverse the class dynamics. “We will put an end to the culture of corruption that has allowed billionaires like Trump to evade taxation and exploit tax breaks,” he argues. “We will stand alongside unions and expand labor protections because we know, just as Donald Trump does, that when working people have ironclad rights, the bosses who seek to extort them become very small indeed.”

There is a concreteness to his approach. This is not about abstract hope. It is about concrete expectations. “Our greatness will be anything but abstract,” Mamdani emphasizes. It will be “felt,” Mamdani says, by the residents of New York who will see their rents capped, who will find child care, who will realize greater affordability. These are tangible outcomes and clear policy goals.

Mamdani is setting forth a critical theory of social struggle. He is making clear demarcations. He is taking sides. Elsewhere, I have argued for a different theoretical approach that focuses less on government run programs and more on worker and consumer cooperatives supported by the municipality; but we can set that aside, the theory needs to be in movement. What I see in Mamdani, though, is the exact kind of new philosophical practice that I tried to sketch out above, drawing on Althusser’s insights.

Bernie Sanders

I see it as well in the wide-ranging interview that Bernie Sanders afforded David Leonhardt of the New York Times. Sanders, like Mamdani, makes a sharp demarcation between the different classes in society, and takes sides with the working class.

Sanders essentially divides the political landscape into, on the one hand, the wealthy and the corporations, and on the other hand ,the working class. These are his words, and his dichotomy. Traditionally, the Democratic Party had been the party of the working class. Sanders emphasizes this: “Throughout the history of this country — certainly the modern history of this country, from F.D.R. to Truman to Kennedy, even — the Democratic Party was the party of the working class. Period. That’s all your working class. Most people were Democrats.” He argues that, starting in the 1970s, the Democratic Party “began to pay more attention to the needs of the corporate world and the wealthy rather than working-class people.” And he wants to reverse that.

“Our job is to create an economy and a political system that works for working people, not just billionaires,” Sanders exclaims.

In addition to class, though, Sanders, like Mamdani, is also attentive to gender, race, youth, and other identities. With regard to the Democratic Party, Sanders argues for a more open and diverse party—beyond simply the working class. “Open the door to young people. Open the door to people of color,” he exclaims. “We’ve got to end sexism. We’ve got to end racism. We’ve got to end homophobia. Very, very important,” he says, indicating clearly the other dimensions interlinked with class.

Wealth inequality is at the heart of his theoretical framework—wealth inequality and the need to reduce it. “In America today, we have more income and wealth inequality than we’ve ever had in the history of this country. Over the last 50 years, you have seen a massive transfer of wealth from the bottom 90 percent to the top 1 percent. You have a political system that is dominated by the billionaire class. That’s what Citizens United was all about, that’s what Super PACs are about. So you got Mr. Musk able to contribute 270 million to elect Donald Trump — and Democratic billionaires playing a role.”

Commentators generally refer to these kinds of arguments as “populist.” They tend to interpret the language of the people versus the elites as populism. And to a certain extent, President Donald Trump seized on this language in his own campaign, when he presented himself as an outsider to the Washington elite. There is a way in which populism can stand in for class struggle. It’s the people against the elites—where the people are the working people, and the elites are the rich. Populism is another way of articulating class struggle, which is why moderates are so opposed to populism. But Sanders always brings it back to the working class, and in this sense is more socialist, theoretically, than populist.

However, Bernie Sanders also shows deep respect for people who are unable to work. So it is not just about working or the working class. There is a generosity, and a mutual aid element.

In the interview, Sanders keeps on challenging Leonhardt on what he means by “the Democratic Party.” Sanders asks, What is a party? What is a movement? And he responds that the Democratic Party is not really a political party, because it does not function as a grassroots movement of people coming together and trying to think together. It is simply a few wealthy billionaires meeting at Democratic fundraisers in Manhattan with the leadership of the party.

What he says about borders is interesting too, which is basically that there needs to be a pathway to citizenship for people who are here working. He always tilts toward work. His argument is that most of the undocumented people in the country are hardworking people. “The overwhelming — overwhelming — majority of these [undocumented] people are working hard. During Covid, those were the people in the meatpacking plants. Those were the people who were coming down with Covid and dying. They were keeping the economy going.” So, he argues, “We need to have an immigration policy, but you also need to have strong borders. Period.”

The idea of scapegoating is a key critique in his theory. He says a few times that what fascists do, what autocrats do, is to identify a particular minority and blame everything on them. “And I think what Trump is doing right now is disgusting. It is what demagogues always do. You take a powerless minority — maybe it’s the Jews in Europe during the ’30s, maybe it’s Gypsies, maybe it’s gay people, maybe it’s Black people. You name the minority, and you blame all the problems of the world on those people. That’s what Trump is doing with the undocumented.”

Very important, Sanders attacks the scapegoating and protects minorities who are vulnerable. This is a central aspect of both Sanders and Mamdani.

Also, Sanders is not just attacking or engaging in broadsides of Trump. Other politicians, like Gavin Newsom in California, spend more time talking about “No Kings.” That is not a positive agenda, and does not help us figure out where we really want to go. Maintaining democracy against an oligarch or an autocrat is not enough.

According to Sanders, the Democratic Party lost the election in 2024 precisely because they did not have a vision that people could identify. “They abdicated. They came up with no alternative.” At most, they nibbled at the edges: “What did the Democrats say? Well, in 13 years, if you’re making $40,000, $48,000, we may be able to help your kid get to college. But if you’re making a penny more, we can’t quite do that. The system is OK — we’re going to nibble around the edges. Trump smashed the system. Of course, everything he’s doing is disastrous. Democrats? Eh, system is OK — let’s nibble around the edges.”

Bernie Sanders argues that we need to give a vision of where we are going. And that’s one of the things that Mamdani and Sanders do all the time. They give a vision of where they want to go. Maybe that’s the implication of a new practice of thinking based on sharp demarcations and taking sides: giving a vision of the future, a positive vision.

Sanders demonstrates a commitment to taking sides for a long haul. And not giving up. “Don’t use the words ‘red state’ or ‘blue state,’” he says. “When I hear ‘red states,’ to me it’s an abdication of the Democratic Party fighting for the working class.”

Sanders also fights back against the nationalism and claims of patriotism of Trump, arguing that Trump is undermining the country by empowering the billionaires. He argues for a different idea of patriotism reflected in the sacrifice of so many Americans to uphold democratic, rather than oligarchic, principles. Sanders appropriates the notions of nationalism and patriotism, arguing that they can only be advanced by “a government and an economy that works for all of us, not just a handful of wealthy campaign donors. That’s your nationalism.”

Sanders concludes:

We love this country. My father came from a very poor family in Poland — antisemitism, poverty — came to America and never in a million years — the fact that his two kids were able to go to college. Unbelievable! Unbelievable. That is the truth of millions and millions and millions of people in this country. This is a great country. It has given so much to so many people, and we’re going to do everything that we can to make sure that Trump does not divide us up, does not move us into an authoritarian society.

Mamdani is tapping into the same notion of patriotism and hope when he discusses New York City as such a melting pot of different nationalities and ambitions—when he talks about Steinway, Kensington, Midwood, and Hunts Point, neighborhoods that reflect the diversity of the city.

Conclusion

According to Marx’s eleventh thesis, the task of philosophy is not just to interpret but to transform the world. But to transform the world, you have to have an idea of what you are going to do, what the future is going to look like. Maybe the positive vision is the transformation, the transformative philosophical practice.

It’s important not to make too much out of a mere interview—and the same is true of a victory speech drafted by a speech writer. These are not intended to be statements of a philosophy. Neither Sanders, nor Mamdani are philosophizing. These are just ordinary act of conversation, of debate, of discourse.

But Mamdani and Sanders are pushing against the box of acceptability in their politics. They are fighting against a system that is designed to contain them. It is important to acknowledge that and further explore the philosophical dimensions or the question of the philosophical practice that’s involved in answering questions and setting out a vision and doing politics.

The bottom line, for the time being, is that Zohran Mamdani and Bernie Sanders illustrate a new practice of philosophy. This practice of philosophy is engaged, sharply demarcated, and takes sides. As a result, it develops a positive agenda, a constructive vision for the future, and specific policies. It is a model for a new political era.

Cross-posted on Substack here.

Notes

Special thanks to Parker Hovis, Mia Ruyter, and Jean-Baptiste Vuillerod for conversations and comments on these ideas. A video recording of a conversation with the philosopher Jean-Baptiste Vuillerod on Louis Althusser’s conception of a new philosophical practice can be watched here.

[1] Louis Althusser, Lénine et la philosophie, pp. 5–47, in Louis Althusser, Lenin & la philosophie, suivit de Marx & Lenin devant Hegel (Paris: François Maspéro, 1972), at p. 20.

[2] Althusser, Lénine et la philosophie, p. 22.

[3] See Jean-Baptiste Vuillerod, The Birth of Anti-Hegelianism. Louis Althusser and Michel Foucault, Readers of Hegel, Paris, ENS Éditions, 2022.

[4] Louis Althusser, « Le retour à Hegel. Dernier mot du révisionnisme universitaire » [1950], p. 243-260, dans Écrits philosophiques et politiques, t. I, éd. par François Matheron, Paris, Stock-IMEC, 1994, at p. 256; Louis Althusser, “The Return to Hegel,” in The Spectre of Hegel: Early Writings, trans. G. M. Goshgarian, ed. François Matheron (New York: Verso, 2014 [1950]).

[5] So, for instance, the MAGA movement looks back to a time when America was “great.” That would be the wrong direction. The new philosophical practice must look forward to a time that American society will be more just than it ever was before.

[6] See, e.g., Lucie Rondeau du Noyer, “Legotien, avocate de Rytmann,” La pensée, vol. 424, pp. 1-8; Emission 175 : Retrouver Hélène Legotien (1910-1980), avec Lucie Rondeau Du Noyer, available at https://cheminsdhistoire.fr/emission175/. Lucie Rondeau de Noyer has also created a website with archival documents for a special collection from the IMEC of Hélène Legotien Rytmann materials here: https://imec-archives.com/qui-sommes-nous/communiques-de-presse/la-collection-helene-legotien-a-l-imec