By Bernard E. Harcourt

“In the following chapter, Karl Marx will be criticized.”

— Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, “Labor” (1958, p. 79)

In her chapter on “Labor” in The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt developed a critique of Marx for not differentiating properly between the concepts of “labor” and “work.” This distinction and Arendt’s reading of Marx played a significant role in late twentieth-century debates in political theory. As Seyla Benhabib notes in her book The Reluctant Modernism of Hannah Arendt (2003), “the aspect of Arendt’s theory of human activity that has been most criticized and discussed … is the distinction between labor and work.” (130)

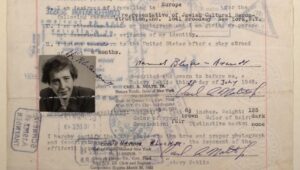

In this keynote lecture by Professor Benhabib, the Eugene Meyer Professor of Political Science and Philosophy emeritus at Yale University, senior research scholar at the Columbia Center for Contemporary Critical Thought (CCCCT), professor at Columbia Law School, and a foremost authority on Arendt, we will explore the controversy over Arendt’s reading of Marx.

In The Human Condition, Arendt identifies three ways of being, three modes of existence. The first is what she calls “labor.” Arendt defines labor as the actions that humans take in order to sustain their lives. It is the labor that one does to stay alive, such as the labor of making food that we consume, making shelter for ourselves, and reproducing ourselves as humans. This aspect of our lives is characterized by consumption: the product of our labor is something that we consume quickly and that evaporates rapidly into our very own subsistence.

The second way of being, Arendt names “work.” The key distinction here is between the animal laborans and the homo faber. Work includes the activities in which human beings create objects and goods that last. Think here of a book that someone has written and created as an object that becomes part of intellectual history, or of paintings and cultural productions. This is the world of making things that outlast us, that are beyond our mere subsistence. The terms we associate with work are “goods” and the “use-value” of goods. They are not merely consumed in the process of sustaining ourselves but remain for future generations.

The third way of being, Arendt calls “action.” This includes political action, doing. It is a form of practice, by contrast to mere contemplation, by contrast to mere theory. On my reading, this is the domain of what the Greeks would have called “praxis.” It is the space where humans collaborate to create a social and political world.

Hannah Arendt suggests that in modern times, humans have come to overvalue labor, over and above the ways of being of work and action. Part of her project in the Human Condition is to recover political action as the privileged space of human activity.

Critics of the distinction that Hannah Arendt draws between labor and work argue that privileging work over labor replicates the problem that feminist Marxists identified in Marx—namely, the fact that Marx focused predominantly on production over social reproduction in the household, or worse, his tendency to ignore social reproduction. If indeed the first way of being that Arendt calls “labor” represents the activities that are necessary to ensure social reproduction—for instance, sexual reproduction, home care, child care, and family activities—then the category of “labor” overlaps considerably with the concept of social reproduction made famous by feminist Marxists. By the same token, what Hannah Arendt refers to as “work” covers most of the production of objects and goods that are the fruit of industrialization. They include not only commodities like cars and refrigerators, the product of industrialization, but also books and paintings and cultural production. They include objects created as a result of industrial and cultural productivism.

On this reading, Marx was not overemphasizing labor over work. On the contrary, he was ignoring labor or social reproduction. And if this is right, the criticism goes, then it seems as if Arendt may have been replicating Marx’s failure by suggesting that we should devalue social reproduction. How then should we assess Arendt’s critique of Marx?

In order to address these questions, we need to take a step back and place Arendt’s critique within the larger context of her writings on totalitarianism and her intellectual trajectory. No one is better placed to guide us with this than Seyla Benhabib, the author, among many other books, of The Reluctant Modernism of Hannah Arendt. It is a privilege to have Professor Benhabib join us for this keynote lecture.

Welcome to the first keynote for Marx 13/13!